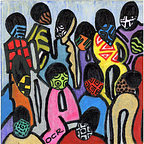

Statement of Colectivo Cuba Liberación Negra (The Cuba Black Liberation Collective)

We are Black queer Cubans who advocate in and outside of Cuba, from an abolitionist and anti-imperialist perspective. Some of us are affiliated with Black liberation groups and the Black Lives Matter movement in the cities and countries where we reside. With this Declaration, we seek to denounce the way the plight of Black Cubans is still being rendered invisible, especially in the context of the economic crisis in Cuba, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and following the protests and demonstrations that have taken place in Cuba from May 11, 2019, until the most recent ones on July 11, 2021. These protests saw thousands of Cubans in cities, municipalities and localities across the archipelago come out against government mismanagement that has contributed to dilapidating the public healthcare system and skyrocketing food insecurity.

Any assessment of the human rights situation of the Afro-Cuban population must begin with an acknowledgement of the persistence of structural racism and racial discrimination (prejudices, stereotypes, racist attitudes, etc.), which manifests itself in all spheres of Cuban society. Popular anti-Black sayings such as “the revolution made Black people people,” reinforce the myth that the revolutionary process ended racial inequality. Furthermore, they ignore the achievements and struggles of the Black population in Cuba prior to 1959 and dehumanize Afro-descendants. These expressions also place Black people in a position of expected subordination, defenselessness and eternal gratitude. Each day, we have to remind Cubans that both enslaved Africans and their descendants have participated in an outstanding way in the island’s emancipatory struggles as well as in its economic, cultural, scientific and social life.

The use of demeaning expressions such as “coleras”, “confused revolutionaries”, “vandals”, “mercenaries”, “delinquents”, “thugs”, “miscreants”, in an attempt to stigmatize those who protest or dissent, reveals a derogatory view of the Cuban people itself, particularly its Afro-descendant population. These expressions embody within themselves both the racism and classism reinforced by government, institutions and the official media, while serving to criminalize those who suffer from poverty and inequality. We cannot overlook the fact that many of the people on whom these labels fall are people of African descent from communities increasingly marginalized by recent economic reforms and vulnerable to abuses of power.

This marginalization of the Black population has to do with the way white hegemony is controlling the spaces of relations (social, economic, cultural, etc.) and also territories. Phenomena such as gentrification in Cuba take on particular characteristics, when they are implemented by the state, which, in vital neighborhoods like Old Havana, displaces the residents to the city’s outskirts in order to build hotels. In the same way, tens of thousands of Black people today live in makeshift settlements, where their basic needs are not met and their legal rights as residents are not protected.

During and after the events of July 11, we have seen countless photos and videos, in which Black people, especially Black youth, are victims of police brutality at the hands of military and paramilitary forces. It is worth noting that the Cuban police force is made up of a considerable number of Black people, many of whom come from the eastern provinces. Considering the conditions of extreme poverty and the obligatory nature of military service, a job that guarantees access to moderately higher salaries can be quite attractive. The above is arguably the most glaring example of how structural racism works in Cuba and how white hegemony instrumentalizes and pits Black people against each other.

However, police brutality does not only refer to the use of physical violence. It also involves many other forms of violence, which while they may be subtler, are equally condemnable. This can include surveillance, harassment, threats, extrajudicial summonses, interrogations, prohibitions to leave the country, police barricades outside homes or in the surrounding streets, etc. It is important to mention that anti-racist activists have also been harassed, persecuted, threatened and arrested for their struggle against racial discrimination. Their partners, family members and friends have also experienced violence.

In addition, the Cuban police frequently practice racial profiling and classify Black youths a priori as delinquents. Consequently, this leads us to question the racial profile that predominates in Cuban prisons; information that the government probably possesses, but so far has not made publicly available. On the other hand, much of the data collected in Cuba’s censuses and surveys are not processed, presented or published according to race. The government likely also has this information, but the racial composition of the incarcerated population is not readily available in Cuba. Nevertheless, it would not be unreasonable to conclude that of the large number of Cubans in prison, the majority are visibly of African descent.

The existence of the legal category known as “peligrosidad” or “danger to the community,” which is intended to contribute to social control, has led to the imprisonment of people considered by the authorities to be “prone to commit crimes” — among them sex workers and drug users. This forces us to wonder whether race is being used, more or less consciously, to determine who is “prone to commit crimes” and who should suffer criminal punishment. Unfortunately, we lack the statistics to confirm this bias in the Cuban judicial system.

In the case of Black queer, non-binary, agender, trans, etc., Cubans, this criminalization is particularly related to the control and policing of their bodies: the way they dress, their gender expressions and their sexuality. They are arrested and imprisoned more frequently than any other group in society, which is proof that the prison system is based on the reinforcement of gender binarism and gender-based violence. The failure to respect names and pronouns, so common in police arrests, is repressive behavior that corresponds to the sex-gender “cis-tem” that white hegemony enforces.

We also want to raise awareness about living conditions in Cuba’s prisons under the pandemic. If the general population is experiencing difficulties tied to COVID-19 health protocols (poor access to resources, food, medicines, etc.), available testimonies suggest that in prisons, the situation is even more critical. This is aggravated by the conditions of social distancing that the pandemic imposes: suspension of family and conjugal visits, overcrowding, isolation inside the prison, increase in the number of infections, etc.

The international debate on punishment, policing, criminalization, the purpose of prisons and the ineffectiveness of the judicial system, propelled by feminist and anti-racism movements, has not yet reached Cuba with the same intensity seen in other countries. This debate focuses on questioning incarceration as a preventive tool, as well as violence enacted through the prison industrial complex and the invisibilization of the plight of Black incarcerated queer, non-binary, agender, trans people, etc.

Our approach is to think of alternatives and strategies against systems that oppress and prevent us from living a dignified and emancipated life. It also implies guaranteeing the human rights of prisoners while working towards ending the use of incarceration as a means of social control. It is about reorganizing the way we live collectively, so that we choose life-affirming systems over death and punishment.

Considering all of the above, we demand authorities:

- Drastically reduce the prison population and end the use of prison as the default mechanism for addressing social problems.

- Decrease funding for the police force, weapons, patrols, etc.

- Promote policies and educational campaigns against anti-Black racism and racial discrimination.

- Stop the criminalization of the exercise of civil and political liberties.

- Guarantee the participation of citizens in the political life of the country with autonomy from the State and its institutions.

- Stop the criminalization of the Afro-descendant population and of people in conditions of social and/or economic vulnerability.

- Eliminate the concept of “dangerousness” from the Cuban penal code.

- Guarantee public access to the latest disaggregated data on the number of prisons, the number of people serving a criminal sentence and their distribution by age, gender, city/town of origin, race and skin color, crime charged, etc. Publish such information on official sites and in the official press.

- Adopt urgent measures to respond in a timely manner to the problems in the prison systems being exacerbated by the pandemic.

- Ensure due process in all trials, end arbitrary detentions and respect the rule of law.

- Promote public debate on policing and prisons in Cuba, in the media and the educational system, including questioning the use of punishment to solve social problems.

- Guarantee full and unconditional access for persons deprived of liberty to health services, hygiene, visits from family and friends, adequate food, recreational activities, etc. Such measures should not be aimed at creating a stronger penal system, but at abolishing it.

- Invest in social resources that contribute to true public security based on social justice, well-being and equity.

- Free those imprisoned for political reasons in Cuba.

The Cuba Black Liberation Collective

Authors: Odaymar Cuesta, Sandra Alvarez and Marlihan Lopez

July 30, 2021