Award-winning journalist Sirin Kale on families, borders and the moments missed | Podium

Today I’m thrilled to introduce you to an exciting young writer and journalist, Sirin Kale. Over the last year, Sirin has covered a dizzying variety of topics that range from international importance to very personal. Some of her recent work:

- Gen Z, fast fashion and climate change

- the hidden world of cats

- an epidemic of flashing and indecent exposure in the U.K.

- how she broke her own addiction to Diet Coke

Her talents earned her a new column titled, “Guardian Angel,” in The Guardian’s recently launched Saturday magazine, where she “makes nice things happen for nice people.”

For Podium, I asked Sirin to write about anything she wished and she chose family and borders — particularly the moments she’s missed with her loved ones spread out across Australia, Brunei, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and the U.K.

I know this is a sentiment we can all relate to, whether your family lives hours or half a world away. I hope you enjoy Sirin’s piece and share it with those close to you.

Finally — for next week’s issue I will be answering more mailbag questions! If you are in need of any advice or just want to know something about me, please leave a question in the comments below and I will try to answer it.

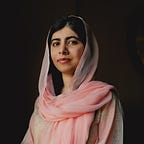

— Malala

We are apart

My niece has been alive for 238 days, and from 10,262 miles away I have watched the days of her life drop away like the petals of a flower, one by one, on social media.

Here she is lying, adorably, beside a puddle of her own fluorescent vomit. Kicking her legs to pop music; screeching in glee at her favourite toy. Now she is sitting up for the first time, tiny body tense with the effort of supporting her head. She is attempting to speak, tongue snagging on tricky consonants like a coat on an exposed nail: th, w, v. Her once-unfocused eyes now track the screen during our video calls. Chubby hands grab for the phone. She is already a different person now, and I will never know the baby she once was, how she smelled, the weight of her, the intensity of her palm gripping mine. Those days are lost, and so are the days to come: her first steps, her first words, her first temper tantrum.

My sister and her daughter live in Brisbane and I live in London. I cannot enter Australia as a U.K. citizen, and a 24-hour flight back to the U.K. with a newborn baby is too much to ask.

So, we are apart.

So many of us have been parted during this pandemic era. Like a toddler crayoning a fresh white sofa, the world has been scribbled on crudely in ink: here are the red-list countries, the amber, the green. The privileged amongst us, people, like me, with Western passports, travel as freely as it is possible to travel in these pandemic times, griping about the cost of Covid-19 tests, and downloading certificates to show that we have been injected with vaccines that our governments hoard from poorer nations in desperate need.

But even with all the privileges afforded to me by the fact that I am a British citizen, I’ve still spent most of the last year-and-a-half separated from my family. My father lives in Brunei, an island kingdom that locked down at the start of the pandemic and doesn’t let anyone enter without government permission. For most of the first and second waves of the pandemic, my ageing grandparents were stuck in their home in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The border was closed with the south, and Turkey was on the red list, meaning there was no way to get them out.

Video calls with them were distressing and disturbing in equal measure. My grandmother kept losing her teeth and her money. The house was overrun with feral cats. (Thankfully, we have now been able to bring them home.)

I have spent so much of the last year thinking about borders, these man-made lines that traverse our geography, and how they are often an adjunct to a pointless and dehumanising nationalism. It is only through historical accident and the tenacity of my ancestors that I am able to travel the world freely. Had my mother and father not moved here from northern Cyprus and Iran in the 1970s, I’d be one of the people for whom borders aren’t an abstract concept but the red scrawl that blots out their hopes and dreams for the future. When I travel, officials wave me through with a bored gesture. I will never see the flat palm of a border guard’s hand, or the butt of their rifle.

As I write this, the world is starting to open back up again. Foreign nationals will be allowed to visit the U.S., if they can show proof they’ve been vaccinated against Covid-19 — meaning that, realistically, only travellers from wealthy, vaccine-hoarding countries will be able to visit. The U.K. recently announced that it would be scrapping the amber and red lists, meaning that only visitors from red-list countries will have to quarantine. (In practice, the countries on the red list tend to be low or middle-income, with less appeal to wealthy tourists from the U.K., for whom the rules can be bent a little, to accommodate their whims. Countries like Ghana and Kenya have much lower Covid rates than the U.K., yet mystifyingly are on the red list.)

It’s hard not to see these travel restrictions as the start of something darker and more disturbing. No — not a global plot from Bill Gates to microchip the world! But a world of harder borders, as the writer Nesrine Malik recently observed in The Guardian. “It’s hard to shake the impression that there is a desire…to use this opportunity to make it permanently harder to move around, particularly if your starting point is in the global south,” Malik wrote. As global warming intensifies — Madagascar is currently experiencing the world’s first climate-change-induced drought — it seems inevitable that there will be more razor-topped walls between wealthy northern countries, and those in the global south.

And in those places, there will be girls like I might have been, if my life had not branched off in a different direction, many years before I was born. Girls whose parents never found themselves in a chilly, unfamiliar country with their possessions in suitcases and a yearning for home. When the world opens back up again, I’ll be there to hold my niece’s hand and watch her blow out the candles on a belated birthday cake. If I believed in God, I’d thank him for my unreasonable good fortune. But I don’t, so I thank my parents instead.