Entrepreneurial Reflections: Blackness, Privilege, Bikes & Red Tape

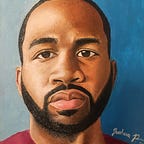

For a variety of reasons, both personal and professional, this seems like a good moment to pause and reflect on my entrepreneurial journey, which began a little more than two years ago. Over the next couple of weeks, I’ll be sharing some thoughts about key moments in my quest to develop smarter infrastructure for bicycles and scooters, along with some of my learnings and takeaways.

In this post, I’ll share some frank observations on privilege, race and power, with a specific eye towards the systemic challenges that affect some founders as they bring products to market within the dynamic world of the urban streetscape.

Where it Began

A little more than two years ago, I bet everything on bicycles. Specifically on the belief that bicycles, scooters and other forms of “micro” transportation would be the next major revolution in cities. Long perceived as just a market niche, I saw these emerging “micro” transit forms as a way to reduce traffic congestion, while complimenting mass transit systems and enhancing local public space. Bicycle transport coheres with all the emerging (and broadly popular) tenants of the new urbanist philosophy towards neighborhoods and urban space, and so enjoy substantial support at the municipal DOT level. In fact, cities from New York to Los Angeles had spent billions, and were poised to spend billions more, to remake their streets for the bicycle.

Yet, relatively little attention is paid to supporting infrastructure. While streets became dramatically safer for cyclists with new bike lanes, public parking options are rare, and you can completely forget about charging an e-bike or scooter.

The dearth of this much needed infrastructure will inhibit bicycles from ever becoming convenient and accessible to most people.

To change this, I set out to think through the right way to bring this kind of infrastructure to cities like New York. After having spent over a year listening to stakeholders in real estate, community development, government and transportation advocacy we launched Oonee, a modular kiosk that bundles public space amenities with essential solutions for micro transit options. Unlike previous solutions in this space, we focused specifically on scale; creating a framework that would allow this much needed infrastructure to spread to an entire network of locations, even in the most densely populated metro areas.

“It’s Great That You know All These People”: Networks & Urban Innovation

At the beginning, a mentor advised me to carefully retain all the contacts that I had garnered during my time at the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership. “It’s great that you know all these people,” she said. “They’re about to become extremely important.”

To date, almost all of our team’s accomplishments stem, in one form or another, from relationships. While I would like to think that grit and tenacity bear a stronger connection to our work than the size of our proverbial rolodex, the truth is that New York is an incredibly chummy place to do business. Deals get done based on the strength of interpersonal relationships, which often originate from familial, schooling or shared professional ties. My ability to navigate this space is largely related to the privilege I acquired during my younger years. I realize this fact now more than ever.

St. Andrew’s School, one of the nation’s elite secondary schools, led me to Tufts, one of the nation’s elite universities. In turn, this led me to Coro, New York’s premier leadership development fellowship, whose network helped me land a job at the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, where I eventually became the Deputy Director of Operations.

The network I aquired there would play a pivitol role in launching Oonee. I met my co-founder, partners, and investors via the relationships that I formed during those years. By extension, our beta testing period at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and our pilot in Downtown Manhattan were directly enabled by this network of contacts.

The cultural capital I acquired during my schooling years have served me well as I move through this space. I’m relatively comfortable with proximity to power and influence, and I can thrive in a variety of social setting. I know how to speak, dress and behave in settings that would have been foreign to me as a teenager. I am fluent in norms that would have likely been foreign to me without the privilege that was gifted to me during those years.

While I probably do not fully appreciate the extent to which these advantages govern my existence, I realize that the vast majority of black and brown people do not have these tools and, therefore, are at a severe disadvantage in if entering this sector. I have not yet formed a fully cogent perspective on ways to remedy these structural gaps, but it’s something I am actively thinking about.

“Wow, you’re really educated!” Blackness Within Privileged Spaces

Yet, the longer I maneuver within this world, the more I am forced to reckon with the real limitations of acquired privilege. I might be able to mask my working class background with eloquence and “in-crowd” jokes, but people will often view you through the context of blackness. This may not come as a surprise to many, but the extent to which this is true still surprised me.

Two incidents stand out in my memory as directly illustrating this fact.

As I opened an informal, friendly meeting with a prospective investor in 2018, he quickly asked a few pointed questions. Upon my answering them, he exclaimed “Wow, you’re really educated!”

It’s hard to envision him saying that if I were White.

The effective translation was “wow, people who look like YOU are not usually this educated!”

In another meeting earlier this year, I told a prospective partner that I grew up in Bed-Stuy Brooklyn. “Were you ever a member of a gang?” he earnestly replied. Again, I doubt this question would have been asked if I were white.

Both of these meetings were informal and friendly, which led me to contemplate the questions and thoughts left unsaid in less candid environments. How many times has a biased assumption pertaining to my background changed the course of a meeting or affected a deal?

The recent spate of documentaries on the disastrous Fyre Festival, and fraud perpetrated on investors by CEO Billy McFarland provided me with an additional reflection point.

Raising our first round of capital was a challenge for me. Prospective investors poured over my financial projections and grilled me on every aspect of the business. Inevitably, so many would, politely, say “not interested.” McFarland, with fraudulent documents and a dubious strategy, raised more than 26 million; way more than I did, with much less. Yes, McFarland is a uniquely smooth salesman, but he’s also the a wealthy white man from New Jersey, who was raised in a well connected circle.

The unfortunate reality is that to be successful at raising capital as a first time black entrepreneur , you must be uniquely talented, unusually well connected and have an amazing product or concept. The barrier is higher for completely black teams and solo founders; they do not have other team members to dilute the cold blow of bias.

How many talented black founders have failed due to the increased difficulty of raising capital or closing deals? How many have accepted deal terms that were less favorable than what would have been offered to a White man with a similar product and resume? It’s hard to tell without more empirical research, but given the enormous racial gap that exists in these kinds of spaces, race is likely an important factor.

“You just need the person with the right juice to make the right call:” Power & Innovation in New York

Aside from fundraising, access to power is a critical factor in the world of urban innovation. In cases where founders lack deep connections to influencers, this can represent yet another key barrier.

I’ve experienced this directly in my challenges at navigating New York’s public property sponsorship and advertising restrictions. We planned the launch of our first kiosk in close partnership with the relevant city agencies, and received a commitment for flexibility on media content in public space. I had taken great care to ensure that our product carefully aligned with the goals expressed by the mayor, and the 2016 strategic plan released by the City’s Department of Transportation. Our effort more advanced, better designed and closer to market than similar government sponsored initiatives, and so their cooperation made sense.

But then the rug was pulled out from under us.

Although we had received a verbal commitment from city officials that we could the include sponsorship and marketing space on the exterior of the kiosk, we quickly found out that there was no clear definition of what that meant within city agencies. In the absence of clear guidelines, agency lawyers took an extremely restrictive view of what was permitted; one that made it virtually impossible to monetize.

Our first sponsorship deal, worth an estimated $40,000 quickly collapsed in this new operating climate, and future prospects dried up. After having spent a year negotiating a permit, and nearly $100,000 in precious seed capital to build a public space amenity, the central component of our revenue strategy was cancelled. Thereby affecting our ability to finance new deployments and to raise capital.

“Many city projects break rules all the time, but they have powerful committed champions who can make calls and sway bureaucratic positions. You need to find that person.”

The supportive officials were now dispassionate. They would try to help, but the lawyers had spoken, and could not be easily overruled. Although they appreciated the strategic value of our project to the city’s cycling community, we were on our own.

Over the next few months we desperately sought advice from other officials, seeking any intervention or strategy to salvage the project. While we received many pieces of sympathetic advice, one still sticks out: “You need someone with the right juice, to make the right call.”

“Many city projects,” the senior official explained, “break rules all the time, but they have powerful committed champions who can make calls and sway bureaucratic positions. You need to find that person.”

Who Has The Power To Get Things Done?

Our current predicament has encouraged me to consider another factor in addition to privilege; power. While privilege can be defined as a seat at the table, power is about the ability to persuade and get things done once you’re there. In an idealized world, I should like to believe that merit is the foremost factor in determining the success of an idea or project, but this is not always the case especially when it comes to public spaces and cities.

In my case, even though the product was successful and well regarded, our ability to persuade people to intervene on our behalf was very limited. Without a well placed phone call, I was told, this problem was not likely to get resolved. More often than not, however, these types of phone calls are not made out of sheer altruism; owed favors, family connections and other ties play a dominant role.

Race and class play a large role in determining who has access to these levers of power; younger founders from non-traditional backgrounds are far less capable at calling upon powerful relationships and favors to help move projects through the bureaucratic process.

The daily lives of New Yorkers are dominated by the effects of public-private partnerships; the machinations of non-government actors craft our relationship with public space. You need not look far: Citibike, for example, is operated via a partnership of Lyft and NYCDOT. LinkNYC is a city franchise that is operated by Intersection, even the city’s bus shelters and newsstands are largely under the charge of JcDecaux, the world’s largest outdoor media conglomerate.

Though they play an oversized role in the daily experience of New Yorkers, these companies are led by a class of people that does not reflect the demographic makeup of the city upon which they affect; they’re mainly white men. This group of powerful people, backed by large corporations, are well positioned to influence the city bureaucracy.

New York could only benefit from greater inclusivity and participation in the conversations that determine the physical makeup of the streetscape. Our city is a majority black and hispanic, we need these communities at the table if we are going to implement services and programs that truly maximize impact. Inclusivity is the cornerstone of effective governance.

This is impossible, however, if traditional power and influence are the only means by which anything of substance is accomplished. A status quo predicated primarily on social capital will only serve to exclude people like me from impacting policy through social entrepreneurship.

“Your Business Model is Not Our Concern:” Equity and Access in City Innovation

During the course of our dialogue with city officials, a common refrain emerged: “Your business model is not our concern.” Ostensibly, this line of thought can make some sense, as city officials may see their work as advocating for public priorities, not concerning themselves with how a startup makes money.

But what if, as in my case, a startup’s entire business is devoted to delivering a recognized public benefit?

Secure bicycle parking facilities is specifically recognized a priority for the city, and our entire operating model was designed to deliver this. If regulatory hurdles prevent us from staying in business, it’s a setback for the entire city, not just us.

Of course, the viability of larger private companies can be the City’s concern. If Lyft, for example, went bankrupt and shut down Citibike, it would certainly bother public officials. If Con-Edison became insolvent, it would disrupt reliable electricity delivery to many millions. It was only a few months ago that we saw the City and State pull out all the stops in an attempt to lure Amazon to Long Island City.

Although they’re not as established as Lyft or Amazon, New York can similarly benefit from partnering with startups, especially those that aim to address urban issues. Startups are agile and nimble. Often untethered to traditional approaches, they’re often more tolerant of risk and have a greater interest in iteration. From a policy standpoint, this can make them ideal partners.

But what they lack is capital. Many startups, like mine, simply do not have the money or runway to withstand the delays and shocks that can come in working with public space. What might be a minor setback for an established firm, could represent an existential crisis for a young one. What a year might represent a “blink of an eye” to a city agency, it’s a lifetime for a startup.

Cities can help by making it easier to cut through red tape so that startups can bring pilots and experiments to urban spaces. Helping to shield a startup, like mine, from often slow pace of city government can benefit both parties.

New York, especially, has tremendous advantages that can be leveraged. The City simultaneously controls some of the most valuable real estate in the world, and represents an enormous potential customer; these assets can be used to develop new solutions that address critical challenges.

On the other hand, New York has long prioritized small businesses development; in fact, there is an entire department dedicated to supporting small business in New York. It’s definitely a concern. That focus makes sense; not only is small business an essential part of the local economy. Small businesses are also a wealth creation vehicle for working and middle class communities.

Startups, with are often associated with technology, design and rapid growth have been a particular focus of the past two administrations for a variety of reasons. The city offers a variety of programs and incubators designed to contribute to the startup ecosystem, we’ve participated in two of these programs. The advantages we gain there do not come close to the challenges that we face in working with City government to bring our product to market.

Yes, incubation and mentorship are certainly helpful, but the prospect of successfully piloting on New York City streets is far more lucrative, especially in the world of streetscape hardware. As the biggest stage in the country, even a successful small or medium sized pilot could be a game changer for prospective partners and investors. For the increasing number of early stage companies like mine, who are looking to innovate public space, this would be a game changer, and the city is uniquely positioned to offer access to this precious resource.

Though this would require no money, it would require the City to eliminate some of the red tape that often prevent innovation; in our case this would mean streamlining the real estate acquisition process (it can take over a year to successfully get an agreement for public space) and creating a realistic set of rules for sponsorship and marketing content in the public space realm. Under this leaner framework, startups like mine could not only provide amenities and services to the public, but would also grow and hire locally.

When it comes to public space, larger corporations have the resources to hire lobbyists and to spend years working to implement a pilot, but startups and small businesses simply can’t do this. New York only stands to benefit tremendously by evening the playing field

Recognizing Systemic Challenges For Black and Non-Traditional Founders

I have a long way to in order to get to a more complete understanding of the function that race and privilege play in this space. However the last two years have blessed me with a perspective informed by two vantage points; a relatively white collar, privileged professional, with a blue collar, working class background.

In his acclaimed 2004 book, “Limbo” journalist Alfred Lubrano refers to himself, and people like me, as “straddlers;” people who come from two different class backgrounds and are not really at home in either. In my case, I entered the world of social entrepreneurship with a distinctly privileged pedigree; top tier schools, a compelling resume. Simultaneously though, I have no family wealth, very little in terms of a safety net, and I certainly can’t think of any people that owe me “favors” in the professional sense. I am both an insider and an outsider.

I initially hesitated to publish this post; it’s languished on my computer for several weeks. It’s considered taboo, for a variety of reasons, for a founder to openly discuss challenges and weaknesses. It’s risky to to allude to challenges with the City, especially when its departments have so much control over the fate of your venture. It’s even more risky for a Black founder to openly discuss blackness, especially any adverse impacts that systemic biases may have had on their current ventures. Many people will inevitably view this as the “race” card.

That’s not what I am doing here.

I’ve tried to avoid naming specific people and specific agencies wherever I can. I would be remiss if I did not mention the fact that I have met so many great and inspiring people along the way; in all sectors. People have rarely been impolite or unprofessional to me, and it is not my intention to draw a cartoonish depiction of my experience.

I do think, however, that it is my responsibility to share my experiences with fellow and future black founders and to challenge our City to be a bit more democratic when it comes to ensuring that citizens, regardless of background, can fairly and effectively compete for the opportunities that shape the lives of its population. I believe that a more inclusive distribution of such opportunities can only be mutually beneficial; allowing for superior design and implementation of public/private program, while ensuring a more egalitarian and fair economic atmosphere for all.

The best I can do is continue to work on our mission of bringing better bicycle infrastructure to all, while occasionally, and candidly, sharing my experiences along the way.