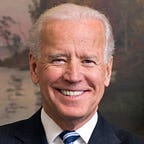

Full Transcript: Vice President Joe Biden’s Supreme Court Remarks at Georgetown University Law Center

Thank you, folks. How are you all? Thank you. Please sit down. My name is Joe Biden.

I’ve worked for Victoria Nourse for a long time. And I mean a long time. And I told the Dean of Students that — when I met him — I almost decided not to do the speech here, although my son went to Georgetown, and my staff went to Georgetown, and son did his first year of law school here at Georgetown. He ended up going — he graduated from Yale. Well, it’s a long story, but that’s what he did. He did his first year and then transferred to Yale.

But I feel a real, intense loyalty to Georgetown. Five Bidens have gone to Georgetown. I went to a good school — I went to Delaware. And I almost decided not to do it at Georgetown and do it at G.W. because you stole Victoria Nourse from me. I thought she had to go back to Minnesota. That’s why I agreed to let her go.

But, Victoria, thank you. You’ve been a great friend, and a brilliant mind, and you’ve helped me negotiate an awful lot of very tough terrain. And I want to thank you for that.

And it’s great to be back here.

Look, last week in the Rose Garden, I stood by President Obama as he fulfilled his constitutional responsibility to nominate to the Supreme Court of the United States Chief Judge Merrick Garland, someone eminently qualified.

If you notice, you’ve heard no one — no one — question his integrity. You’ve heard no one question his scholarship.

You’ve heard no one question his open-mindedness. You’ve found no one to find any substantive criticism of Chief Judge Garland. I’ve known him for 21 years. I’m telling you, you will have great difficulty finding anyone.

Which makes this all the more perplexing. As the President said, Chief Judge Garland deserves a hearing just as a simple matter of fairness — before we talk about the Constitution. But it’s also a matter of the Senate fulfilling its constitutional responsibility.

And yet, weeks ago, my friends — and they are my friends — Republican senators announced that whomever the nominee might be, they intended to abdicate their responsibility completely. That is what they say today, it’s what they said then. What Republican senators say they will do, in my view, can lead to a genuine constitutional crisis, borne of the dysfunction of Washington.

I’ve been here a long time. I’ve been in the majority, the minority, the majority, the minority. I’ve been on both sides. I understand — and if you read, most people would say I have very good relations with the Republican Party as well as the Democratic Party.

But I’ve never seen it like this.

Washington right now — the Congress is dysfunctional. And they’re undermining the norms that govern how we conduct ourselves. They’re threatening what we value most, undercutting in the world what we stand for.

I’ve traveled over a million miles just since being Vice President of the United States, and I’m not exaggerating — I usually go because when I go to meet with world leaders, most of whom I’ve known before, they know when I speak, I speak for the President, because of our relationship. So I spend a lot of time, and I promise you this is what I hear — whether I’m in Beijing, whether I’m in Bogota, whether I’m in the UAE, in Dubai, I’ll try to convince them of a position we have, and they’ll say, okay, and they’ll shake hands. But I give you my word — they’ll look at me and say, but can you deliver? Let me say that again. When the President of the United States speaks, or I speak for him, world leaders will look at me and say, can you deliver?

Those of you who have traveled around the world, or are from other parts of the world, you know that the world looks at this city right now as dysfunctional. And that’s a problem. It’s going to be even more of a problem especially in the Congress.

The great Justice Robert Jackson once wrote: “While the Constitution diffuses power the better to secure liberty, it also contemplates that practice will integrate and disperse powers into a workable government.” Here’s the important sentence. It says, “It enjoins upon its branches separateness but interdependence, autonomy but reciprocity.” Separateness but independence; autonomy but reciprocity.

In my entire career — seven years as Vice President, 36 years in the United States Senate, half of those years as either the ranking member or chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee — I’ve never seen the spirit of interdependence and reciprocity at a lower ebb. Not among our people, but our government. The bonds that held our diverse Republic together for the last 229 years are being frayed.

And you all know it. Whether you’re Democrat, Republican, liberal, conservative — everybody knows it. The world knows it. It limits our people’s and other governments’ trust in us, our trust in each other. This is not hyperbole to suggest.

Without trust, we’re lost. Without trust and give between the branches and within the branches, we’re lost.

Now, back in 1992, in the aftermath of a bruising and polarizing confirmation process involving Clarence Thomas — who had been nominated by President Bush, with no consultation, just four days after the great Thurgood Marshall had retired — I took to the Senate floor to speak about the Supreme Court nominating process. Senate Majority Leader — and my friend — Mitch McConnell, and other Republicans today have been quoting selectively from the remarks that I made in an attempt to justify refusing to give Chief Judge Garland a fair hearing and a vote on the floor of the Senate. They completely ignore the fact that, at the time, I was speaking of the dangers of nominating an extreme candidate without proper Senate consultation. They completely neglected to quote my unequivocal bottom line. So let me set the record straight, as they say.

I said — and I quote — “If the President consults and cooperates with the Senate, or moderates his selections… then his nominees may enjoy my support, as did Justice Kennedy and Justice Souter.” End of quote.

I made it absolutely clear that I would go forward with the confirmation process, as chairman — even a few months before a presidential election — if the nominee were chosen with the Advice, and not merely the Consent, of the Senate — just as the Constitution requires.

My consistent advice to Presidents of both parties — including this President — has been that we should engage fully in the constitutional process of Advice and Consent. And my consistent understanding of the Constitution has been the Senate must do so as well. Period. They have an obligation to do so.

Because there was no vacancy after the Thomas confirmation, we can’t know what the President and the Senate might have done. But here’s what we do know.

Every time — as the ranking member or chairman of the Judiciary Committee, I was responsible for eight justices and nine total nominees to the Supreme Court. More than — I hate to say this — anyone alive. Oh, I can’t be that old. Some I supported; a few I voted against. And in all that time, every nominee was greeted by committee members. Every nominee got a committee hearing. Every nominee got out of the committee even if they didn’t have sufficient votes to pass within the committee. Because I believe the Senate says the Senate must advise and consent. And every nominee, including Justice Kennedy in an election year, got an up and down vote.

Not much of the time. Not most of the time. Every single, solitary time.

So now I hear all this talk about the “Biden Rule.” It’s, frankly, ridiculous. There is no Biden Rule. It doesn’t exist.

There’s only one rule I ever followed on the Judiciary Committee — that was the Constitution’s clear rule of Advice and Consent.

Article II of the Constitution clearly states, whenever there is a vacancy in one of the courts created by the Constitution itself — the Supreme Court of the United States — the President “shall” — not “may” — the President “shall” appoint someone to fill the vacancy, with the “Advice and Consent” of the United States Senate.

And Advice and Consent includes consulting and voting. Nobody is suggesting individual senators have to vote “yes” on any particular presidential nominee. Voting “no” is always an option, and it is their option. But saying nothing, seeing nothing, reading nothing, hearing nothing, and deciding in advance simply to turn your back — before the President even names a nominee — is not an option the Constitution leaves open. It’s a plain abdication of the Senate’s solemn constitutional duty. It’s an abdication, quite frankly, that has never occurred before in our history.

Now, unable to square their unprecedented conduct with the Constitution, my friend, Mitch McConnell, and chairman of the committee — and he’s my friend — the Senator from Iowa, Senator Grassley, they’re now trying another tack. They ask: What’s the difference — what difference does it make if the Court has eight members or nine members? No, I’m serious. Remember, they said they weren’t going to fill any vacancies on the Circuit Court of Appeals for the District for four years. Remember that’s what they said. But that’s not a constitutionally created court. The Supreme Court is.

So let me make clear for folks who may be listening at home, what happens — and you students all know this — but what happens at the Supreme Court makes a significant difference in the everyday life of the American people.

Article I gives the power to Congress to fix the number of justices. From 1789 to 1866, the number waxed and waned between five and 10. But in 1869, the Congress passed a law setting the Court’s size at nine, and that law has not been changed since.

As recently as 1992, I said on the floor of the Senate — as pointed out to me, for me — that it was “no big deal” for the Court to go through a period of four-four splits, partly because the period wouldn’t last very long, so the exact number of justices was of less urgent concern. But I don’t believe anybody in their right mind would propose permanently returning the Court to a body of eight. Or leaving one seat vacant not just for the rest of this year, but for, potentially, and likely, the next 400 days. That option wouldn’t be much better.

This is all the more true in an era when Congress has become almost entirely dysfunctional. And no one other than the deceased Justice Scalia wrote, if you have eight justices on a case, it raises the “possibility that, by reason of a tie vote, [the Court] will find itself unable to resolve the significant legal issues presented by the case.” If that possibility becomes reality in any given case, the justices would have to announce that they cannot decide either way. They will be left clearing the case from their docket or kicking it down the road to be reargued under a new court when a justice is finally confirmed.

Pressing controversies that prompted the Court to grant review in the first place, in many cases because of different decisions in different circuit courts, would remain unresolved.

The issues the Court believes were too important to leave in limbo are going to remain in limbo, suspended in midair.

More than two centuries ago, Justice John Marshall famously declared that the Court “has the duty to say what the law is.” Not an option — a duty. A solemn duty. And when the Senate refuses even to consider a nominee, it prevents the Court from discharging that constitutional duty in a so clearly ideologically divided court. Disabling the Court by keeping the seat vacant for hundreds of days matters not just because of the uncertainty it perpetuates, but because of the way it fractures our country.

The Framers designed our system to give one Supreme Court the responsibility of resolving conflicts in the lower courts. If those conflicts are allowed to stand, we end up with a patchwork Constitution inconsistent with equal justice and the rule of law. Federal laws that apply to the whole country will be constitutional in some parts of the country but unconstitutional in others. I don’t have to go through the cases you know that are pending appeal and how controversial they are. The meaning and extent of your federal Constitution, your constitutional rights — freedom of speech, freedom to follow the teachings of your faith, or to determine what constitutes teachings of your faith, the right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure — all could depend on where you happen to live.

I think most people in this country would think that’s unfair and unacceptable.

We are, after all, the United States of America. Either the Constitution protects rights across the United States, or it doesn’t. A patchwork Constitution is hardly a national Constitution at all.

And a divided Supreme Court would be unable to establish uniform federal law.

That could mean, as you students well know and your professors, claims of race or sex discrimination could come out one way in California and Arizona and another way next door in Utah or Colorado. Claims of government interference with religion could have one fate in Ohio and Iowa and another in nearby Illinois and Wisconsin. Look at the cases. Claims of unlawful policing might be resolved by one standard in Nebraska and a totally different standard next door in Kansas. There’s nothing implausible about these scenarios.

The American people deserve a fully staffed Supreme Court of nine. Not one disabled and divided, but one that is able to rule on the great issues of the day: Race discrimination. Separation of church and state. Whether there’s a right to an abortion — and if so, safe and legal abortion. Police searches. These are actual cases before the Supreme Court of the United States, before the courts. We have to make sure that a fully functioning Supreme Court is in a position to address these significant issues, and that geographic happenstance cannot fragment our national unity.

Unless you think is exaggeration — when studied Brown vs. the Board, remember that Chief Justice Warren had the votes to decide that case, but he waited to get one Southern justice to rule with a majority, because he knew what it would do in dividing the country if that were not the case. Extrapolate that to today, the same principle about one Constitution — why it’s important that these laws be applied and the Constitution be applied the same way everywhere in the United States. I realize it’s not exactly analogous, but think of what it says about how important it is.

Alexander Hamilton had the foresight to warn that such fragmented judicial power would “create hydra in government from which nothing but contradiction and confusion can proceed.”

Even worse, a patchwork Constitution could deepen the gulf between the haves and have-nots. Under a system of laws, “national” in name only, the rich, the powerful can use it to their advantage, the geographical differences, and game the system not available to ordinary people.

Look, our democracy rests upon the twin pillars of basic fairness and justice under law. You law students, you’re going to be asked to write essays and exams about what both those things mean. But every American knows in their gut what they mean. They understand it. It’s intuitive. Both these pillars demand that we not trap ordinary Americans in whatever lower court’s fate has chosen for them, while letting other more powerful selectively choose lower courts that best fit their needs. I know there’s forum shopping now.

Look, the longer this high court vacancy remains unfilled, the more serious the problem we will face — a problem compounded by turbulence, confusion, and uncertainty about our safety, our security, our liberty, our privacy, the future of our children and our grandchildren.

At times like these, we need more than ever a fully functioning Court, a Court that can resolve diverse issues peacefully, even when they resolve them in directions that I didn’t like. Dysfunction and partisanship are bad enough on Capitol Hill. But we can’t let the Senate spread that dysfunction to another branch of the government, to the Supreme Court of the United States. We must not let it fester until the vital organs of our body politic are too crippled to perform their basic functions they’re designed to perform.

And I think you probably think I’m exaggerating, but think of all the things that have not been acted now, unrelated to the Court up on the Hill, that are profoundly important to the functioning of our foreign policy, our domestic policy, just left unattended. No action. We can’t afford that to spread to another branch of government.

Contrary to what my Senate Republican friends want you to believe, the President and I are former senators, and we take Advice and Consent very seriously, and we did when served.

We do so not just because it’s our constitutional duty, but because we care deeply about getting past the gridlock that has left our people understandably frustrated and angry with the government in Washington. I wonder how many of you have been kidded when you got home — “you go to school in Washington?” Not a joke. They know Georgetown is one of the great universities in the world. But I’m not joking. Go home — “I live in Washington.” I’m serious. Think about it. Think about how we even laugh about. Like, yeah, we all know that’s true. It’s pretty sad.

Look, we, you — we all care deeply about making this government work again. The President and I care about the letter of the Advice and Consent as well as the spirit of Advice and Consent. That spirit — that spirit of accommodation and forbearance — not the spirit of intransigence.

That’s why both of us — why our administration — we spent countless hours meeting with and soliciting the views of senators of both parties, including — I sat there with the Majority Leader McConnell and the Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee in the Oval Office. The President and I spent hours together, admittedly. We sit down, like the three — other two nominees, and we’re the last two in the room. But it hasn’t been a closed process. We’ve reached out. Who do you want? Who do you think? What type of person should we nominate?

We did our duty. The President did his duty. We sought advice. And we ultimately chose the course of moderation because the government is divided.

The President did not go on and find another Brennan. Merrick Garland intellectually is capable as any justice, but he has a reputation for moderation. I think that’s the responsibility of the administration in a divided government. Some of my liberal friends don’t agree with me. But I do. It’s about the government functioning. It’s about the admonition of Justice Jackson.

The President has fully discharged his constitutional obligation. So it’s a really simple proposition in my view. Now it’s up to the Senate to do the same as, I might add, the polling data shows the American people expect him to do. We owe it to the American people to consider his nomination and to give him an up or down vote.

Look, the American people are decent and inclusive at heart.

It’s not in our nature as a nation to shut our minds and treat those with whom we disagree as enemies instead of the opposition.

It’s not the American people who are to blame for this dysfunction. It’s our politics. Our politics are broken. And it’s no secret that Congress is broken. Again, regardless of your political persuasion, I would love to hear one of you in class — and I’ll come back if you invite me — tell me how the system is functioning. Even the most serious and persistent national crises haven’t motivated the current Congress to find a middle ground. They just move it to the side. They haven’t even addressed it.

So, I will end where I began. We are watching a constitutional crisis in the making borne out of dysfunction in Washington. It’s got to stop — it really does — for the sake of both parties, for the sake of the country, for the sake of our ability to govern. It’s got to stop. The defining difference of our great democracy has always been, no matter how difficult the issue, we’ve ultimately always been able to reason our way through to what ails us and to act as citizens, voters, and public servants to go fix it. But this requires that we act in good faith — in a spirit of conciliation, not confrontation — with some modicum of mutual goodwill, for the sake of our country, the country we love, because of what we value. That’s who we are.

We can’t let one branch of government threaten the equality and rule of law in the name of a patchwork constitution. We must not let justice be delayed or denied as a matter of fundamental rights. We must not let the rule of law collapse because in our highest court — because it’s being denied its full complement of judges as a result of the Senate’s refusal to accept the presidential nominee.

I still believe in the promise of the Supreme Court delivering equal justice under law, but it requires nine now. I still believe the voice of the people can be heard in the land if we follow a constitutional path — the path of Advice and Consent writ large, the path of collaboration in search of common ground. For obstructionism is dangerous and it is self-indulgent. And in the greatest constitutional republic in history of the world, it’s a simple proposition, folks. Not a joke. Think of this last statement. Unless we can find common ground, how can the system designed by our Founders function? Not a joke. How can we govern — (phone rings) — if he doesn’t turn off that phone? If it’s my staff, you’re fired. But all kidding aside, just think about it. How can we govern without being able to find common ground? That’s how the system is designed. It’s worked pretty darn well for the last 200-plus years.

One of the reasons I came to a law school — a great law school — to deliver these remarks is I want you, when you go back to class, to challenge what I’ve said.

Look at it closely. Take a look and see whether the argument I’m making is right or wrong. Make your voices heard. Make your voices heard.

I want to thank you all. God bless the United States of America. And most of all, may God protect our troops. Thank you so much.