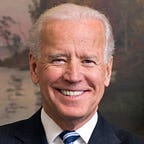

Here’s what I said at the University of Denver on our Foreign Policy:

Vice President Biden delivered remarks at the 19th annual Korbel Dinner at the University of Denver’s Korbel School of International Studies. Below are excerpts from his speech.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I’m an internationalist. Ambassador Hill is. We firmly believe in the overwhelming national interest of the Untied States remains — that we remain deeply engaged in the world. Half of success is showing up.

But for the first time, there is a broad consensus that exists — the one that existed for seven decades, a broad consensus to liberal international order and international engagement is now in question — questioned by a significant minority in both political parties, particularly the Republican Party. But in both parties.

In my view — it’s a real minority — but in my view, this is dangerous. For we’re at an inflection point in world history. Not because of Barack Obama and Joe Biden or any other world leader, but because the world is changing so rapidly and drastically.

###

Folks, everything we face is different than it was 15 years ago. I’m a product as a 29-year-old kid of the Cold War as a senator, with all the old Cold War warriors that I ended up working with. We don’t have 18,000 ICBMs added — nuclear warheads aimed at us now. We have different threats. In a sense less consequential, but more difficult to accommodate and deal with — the fear of the spread of weapons of mass destruction to non-state actors that respond to no constituency, a fundamental shift in energy resources in the world. In the last 10 years, think of the change.

North America — Canada, the United States, and Mexico — is now the epicenter of energy in the world. Not the Saudi Arabian Peninsula, not the Middle East, not Nigeria. North America. Fundamentally altering the landscape. Digitalization and globalization has had a profound impact on attitudes around the world, producing great winners and extraordinary losers. We can neither protect nor advance our interests by turning inward.

###

The day the President and I were sworn in, before that day, we discussed in that interregnum period putting together our Cabinet that the single-most important job we had was to as quickly as we could restore respect for American leadership around the world.

Think back to 2008. It’s not a criticism of anybody.

It’s just a fact. American relationships around the world — even with our oldest allies — were badly frayed. Our judgment, as well as our motives, were being called into question by friends and foes alike.

According to a Gallup poll back then, the United States was ranked behind Germany, the European Union, China — only slightly ahead of Russia in terms of the most respected countries. Now we rank number one as the most respected country in the world again.

That data backs up what I see every time I travel abroad. Not because I’m important just because of the nature of my jobs the last three decades, I’ve literally met every major world leader. Again, not because — just the nature of my job. Many of the world leaders I know now they were legislators in their institutions when I knew them. I don’t know one — not a one — who would not trade places in a heartbeat with the United States of America — friend and foe.

American leadership is more respected and admired today than when we took office — no matter how much our critics try to make you believe, just look at the numbers.

###

Our ability to lead the world and rally nations to our side rests upon — and this is the point I want to make, particularly to the students — on two basic pillars. One, the strength of our economy.

Ladies and gentlemen, after that god-awful recession, we reestablished our standing at the strongest, most innovative major economy in the world — the largest economy in the world. We led the global recovery. We rescued the financial system, stabilizing the economy. And I think it’s important to add, when we did TARP and bailed out the banks, which was like petting snakes. The hardest vote any member of Congress ever had to make. I’m not joking. But we attached to it interest rates to pay back, the public made billions of dollars. And it all got paid back. But, God, it was unpopular.

We turned Wall Street back to the greatest allocator of capital in the history of the world from a casino, preventing another crash, protecting consumers. We invested more than $1 trillion in our economic recovery in — dirty word — stimulus. And America emerged from the global recession faster and stronger than any nation, in large part because of the policies that a very resilient public allowed us to initiate.

Our economy has grown 20 times faster than Europe’s; 100 times faster than Japan. Just this week, notwithstanding all the badmouthing, the Census Department showed that the typical household income was up $2,800 just last year, the fastest growth on record — 3.5 million people moved out of poverty, not into poverty. (Applause.)

So it’s no exaggeration — and by the way, this isn’t about Barack and me, it’s about the grit of the American people. So it’s no exaggeration to say that our economy today is not just recovering, it is on the cusp of resurgence. If we just get out of our own way and do a couple smart things.

The second pillar beyond a strong economy to be able to sustain our leadership in the world is that we had to reestablish our credibility not merely by leading by the example of our power, but by the power of our example. Why does the rest of the world repair to us? Clearly, we are the strongest military in the history of the world. That is not hyperbole. That is not hyperbole. This is the finest, best-trained military in the history of the world. (Applause.)

But that’s not why people respect us and race to come here. It’s because of our value system. Matching our policy to what we say we value. Hillary and I talked about it when she was Secretary of State. We’d meet every Tuesday morning at my house for an hour. I was kiddingly referred to as the Obama Whisperer. What did he mean when he said that to me? (Laughter.) Because I’m the only one that knew everybody in the Cabinet. I’m not being facetious — just because I’ve been around a long time. And everybody from the Department of Interior to the Secretary knew — as my brother-in-law would say I was not trying to cut their grass. I wasn’t looking for any line authority. So I was able to work between the agencies. And we talk about it.

The fact of the matter is we really mean what we say and people think we mean what we say when we say, We hold these truths self-evident that all men are created equal. Sounds corny — endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights. That’s what we thought of. That is that Shining City on the Hill. We’ve never been able to match it, but we have come a hell of a lot closer.

One of the reasons we lost so much respect ranges from Guantanamo, which is a magnet generating more terrorists, to torture, which we have outlawed under any and every circumstance in the United States of America. Period. There is no justification. (Applause.)

And by the way, as John McCain will tell you, it doesn’t work. We began to stand up for the universal rights of all people — for women, for religious minorities, for the LGBT individuals — at home and abroad. Part of our foreign policy our aid is dictated in part by the behavior of countries in terms of how they treat women and girls. It matters. The rest of the world recognizes it. There’s not a country I go to — without exaggeration — that I don’t get because it’s the thing I’ve worked on so much thanks for the Violence Against Women Act. (Applause.) No, it’s not about me. But I’m serious. People notice what we do.

So we insisted that America’s leadership doesn’t always have to be viewed synonymous with the use of force. Even though we have the best, strongest military in the world, but it cannot be our one-size-fits-all response to every crisis.

And we recognized that the most effective leadership often stems from one of our many other strengths — our diplomatic skills, our trade, our economic clout, our generous and effective aid programs. In short, we rebuilt our economy with the help of an awful lot of people and restored our reputation. And these two steps, these two pillars enabled us to remain committed to a liberal international order designed to strengthen democracy, preserve peace, and lift up the lives of people on every continent.

It’s my strong belief that the next administration should build on this momentum.

###

It’s a big agenda. But, folks, I think sometimes, those of us who and many of you sitting on the ice out there, who focus on international relations and foreign policy, we lose sight of the need for a broad consensus among the American public for the international order to be maintained.

No policy can be sustained without the informed consent of the American people. (Applause.) No policy can be sustained no matter how enlightened without the informed consent of the American people.

So as we recommit to advancing an internationalist foreign policy for the 21st century, we have to confront the challenges that have arisen as a consequence, as a result of this more interconnected and open world. Folks, a lot of people are hurting. It’s not all good.

First, we have to recognize that there’s a real anxiety in America and other countries — but I’ll speak to America — real anxiety rooted in security concerns as a consequence of the threat of terrorism. That danger is real, but it’s stoked by those who exaggerate the threat and exacerbate people’s fears for their own political well-being. (Applause.)

Folks, I’ve been criticized for saying it, but I’ll say it again, the American people are so much stronger, so much more resilient, so much more capable than the political leadership gives them credit for.

Boston — what did we do? We responded Boston Strong. We owned the finish line. The people responded to every single crisis we have faced. What has happened? The people of that region have sucked it up, gotten stronger, not abandoned what they know the purpose of terror is to change our system, to change our way of life.

President Obama has never hesitated to use force to defend the American people when necessary. All you got to do is ask Osama bin Laden, al Qaeda’s top operatives in Afghanistan and Pakistan, or the leaders of al Qaeda affiliates in Yemen or Somalia or the 120 ISIL top leaders and commanders who have been taken off the field over the past two years. In Iraq and Syria, ISIL has lost 50 percent of the territory it once held three years ago in Iraq, 20 percent of the territory in Syria, and it’s going to be over in terms of anything remotely approaching a caliphate.

But it’s going to take time. We have to put this in perspective. We’ve taken thousands of foreign fighters off the battlefield. The foreign flow is down 50 percent. They’ve lost tens of millions of dollars in revenue. I used to always hate it when in the Vietnam War, the reason I ran for the United States Senate against that war, when they’d give us body counts. We killed so many more than they killed. That’s not the purpose of my saying this. There is no caliphate. There is no possibility of a caliphate. And the results — we’re winning; they’re losing. But it’s going to take more time. And we should put the threat in perspective. Around the world terrorism must and will be defeated.

Throughout our administration, we’ve kept a laser focus on homeland security. And to the credit of previous administrations, we have the most layered defense of any nation in the world. We have spent hundreds of billions of dollars. And now after not listening to us for so long, our European friends are finally beginning to talk about the need to share intelligence, increased enforcement, better training, passenger lists, a whole range of things. And there’s much more coordination now than there has ever been between us and Europe. It’s been slow. Will there be another attack in the United States like Boston or what we saw in California? If you had to bet, probably sometime there would be. We’re a nation of 320 million people. The American people know in their gut there is no existential threat to the security of the United States of America.

The point I’m trying to make is what’s happened here is technology has changed dramatically. So now the very things that are available to you on your iPhone is able to by terrorists to coordinate.

Cyber security is a real and mounting concern. You don’t need an army to generate an expertise. They’re real concerns. But what caused the hyperventilation in the country is that phone you have. The daily images of violence shared instantaneously all around the world, images you would have never seen 10 or 12 years ago. I’ve actually have people as I go around the country say, look at the television and see the migration flows going through the Balkans, seeing barbed wire fences knocked down, and say, they’re coming.

This has fostered a feeling of lack of control; that we’re being overrun by outside forces. And it’s a basic human reaction, but unfortunately flamed by demagogues — fanned by populist and xenophobic rhetoric, scapegoating immigrants and Muslims.

We see it in Europe. I was in Ireland when the Brexit vote took place. That may be the only vote to ever bring together north and south. Not a joke. Because what happens now is the Republic is still part of the Union, and all the benefits that flow from it, and Northern Ireland is not. They’ve got to work out a modus vivendi on their border now. The impulse is to hunker down, shut the gates, build walls, withdraw, rather than lead boldly is real.

The second thing we have to address is the economic anxiety brought on by globalization, the increasingly rapid movement of people, money, goods and ideas around the world. Because I’m an internationalist, everybody thinks I¹m an unabashed supporter and believer that globalization has been a good thing. It has not been a good thing across the board.

There’s empirical fact that globalization has raised the standard of living for millions upon millions of people the world over. At the same time, it’s also clear that globalization hasn’t been an unalloyed good. There is a much darker side, punctuated by pressures that stoke fears and anxiety; rising inequality; competition from trade with low-wage countries; low wages, lost jobs, whole industries dismantled. It’s created dissatisfaction and a sense of economic displacement. That’s real. It’s not made up. It’s real in many parts of America. It’s real. It’s happened.

For a lot of people in this country, and across the developed world, life feels harder than it used to be. And in the communities that have been hardest hit by the downsides of globalization, the decline was underway. It isn’t a new phenomenon. It’s been going on for decades, but now it is being exacerbated.

The fact is, improvements in technology have increased productivity, which means we can make more with fewer workers. So while we’ve more than doubled our manufacturing output since 1975, we’ve lost 5 million manufacturing jobs.

With the growing demand for high-skilled workers over blue-collar workers, coupled with the competition from low-wage countries, we’ve seen sharp divergence in wages. We¹ve seen labor protections in the United States deteriorate. Fewer benefits, a minimum wage that buys less.

These challenges of globalization are exacerbated by the long-run decline of unionization, which means even sharper erosion of worker pay and protections. A recent study was put out by an economic institution pointing out that $2,700 — that’s how much the average non-union worker has lost in salary due to the reduction in the number of union members in America.

All this translates into less economic security for folks who are just trying to feed their families, send their kids to school. And that’s a scary thing for a lot of people. And I’m not just talking about poor folks. I’m talking about families where the husband and wife both work. They’re making 100,000 bucks a year. They live in Denver. They got three kids, and it’s not easy. We don’t speak to them anymore. Either party. We don’t speak to those folks making between $60,000 and $110,000.

An awful lot of people from the kinds of places where I grew up feel like the basic American bargain has been broken. There was a bipartisan ideal that existed since the late ‘30s, early ‘40s. It was a basic bargain. Both parties supported it: If you contributed to the profitability or productivity of the enterprise with whom you worked, you got to share in the benefits. If you worked hard and got ahead, played by the rules, you’d be okay.

###

And I know some of you are thinking — I thought Biden came here for a dinner at a school of international affairs, why in the hell he’s talking so much about these domestic issues?

But in a globalized world, there is no bright line between foreign and domestic policy. What happens at home impacts on our capacity to have the support of the population to remain engaged in the world. As I said before you need the informed consent of the governed.

To push back against the forces of isolationism, you have to first acknowledge that many of the fears and insecurities driving people the other way, they’re real.

This is a key challenge for the students in the other room that are earning their degrees from the Korbel School today. You’re going to have to grapple with it throughout their careers — how to build and sustain a consensus for an internationalist foreign policy, while managing the disruptions and legitimate dislocations that actually do stem from globalization. It sure in hell isn’t to not engage in trade. It sure in hell isn’t to reject globalization. It sure in hell isn’t to walk away from an international rule-based order. But we have to respond. Or it won’t matter.

###

Folks, we know how to do a lot of this. And so I guess the generic point I want to make, and I’ll get out of your hair before your chairs completely freeze. (Laughter.) Is that it’s important that we understand that without a growing, dynamic economy, our ability to be that change agent in the world for our own safety’s sake diminishes exponentially. We can’t possibly sustain the military we have. We spent more than the next eight nations in the world combined on our military.

The next administration has an incredible opportunity to build. And the students who are at this great institution have to understand that in order to sustain what we know we need, a refinement of the global economic system and continued full-bore engagement of the United States in the world affairs, we can’t do it unless the people at home think they benefit from it, and they’re safer because of it.

So we need leaders like you’re educating here to make the intellectual case with rigor and conviction that the benefits of global engagement far outweigh the cost. We know how to do that. We also have to have a gut understanding of the real pain, anxiety, and fear — some of it legitimate — on the part of the American people. We have to use our domestic policy to bend all this change, to bend the arc of globalization to benefit average people. Every major fundamental change in world history, every major industrial revolution, we’ve been ultimately able to bend so there’s universal benefit as a consequence of it.

Let me say to the students in closing, I said before that we’re at an inflection point. If you’re ever going to be involved in government or policy, the most propitious time to do it is moments of great change because you have your hands on the wheel. With a lot of luck, some discipline, and a little bit of courage, we can bend the arc of history just a little bit. Just a little bit, and we can set a course for the world for the next generation or more just as our fathers and grandfathers did for us—and grandmothers — after World War II.

It’s within our power to do it. I thank you all for listening. Thank you for what you do and may God bless you and may God protect our troops. Thank you very much.