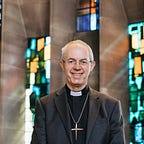

‘We need a narrative of hope’: Archbishop Justin Welby opens House of Lords debate on shared UK values

Read Archbishop Justin Welby’s opening speech in the House of Lords debate he is leading today on our shared national values.

My Lords, I am most grateful to the usual channels for making this debate possible. I would also like to thank noble Lords who have made the time and taken the trouble to attend today in considerable numbers, and to thank the minister, the noble Lord, Lord Bourne, and those who look after us so well in the House.

The motion reads, ‘The Lord Archbishop of Canterbury to move that this House takes note of the shared values underpinning our national life and their role in shaping public policy priorities.’

It will be an especial pleasure to hear maiden speeches from Baroness Bertin and Lord McInnes of Kilwinning. Baroness Bertin brings her knowledge of communications, of issues of disability among children, and of education. Lord McInnes will enable us to have a wider view of issues from Scotland.

The UK, especially perhaps England, is a pragmatic country with a bias towards the empirical over the theoretical. Not for us the cries of ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’, to be followed by years of bloodshed to ensure true fraternity was established. Rather, ours is an untidiness of cumulative reforms and changes, worked out in practice through the highways and byways of our constitution. We relish the irony of a constitution that works in practice, but never could do so in theory.

Great times of change in mood and culture demand from us a re-imagining of what we are about as a nation. As we move into a post-Brexit world, alongside the other events that buffet and deflect us, unless we ground ourselves in a clear course and widely accepted practices, loyalties and values (what I will call values in this speech), we will just go with the wind.

The catalyst for attempting to codify our shared national values — what the Government have called ‘Fundamental British Values’ — is the threat of violent extremism within our country; and also, to a lesser extent, questions about immigration and integration, inequality and our role in the world. But values built on feelings of threat and fear can lead us down a dangerous path.

Practices and loyalties that are not grounded in values of hospitality, generosity and welcome lead to a turning inwards that strangles the hope of the common good.

There is no better example of the expression of good values than in Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan; a story deeply embedded in our collective understanding of what it means to be a good citizen, and which reminds us that our values have not emerged from a vacuum — but from the resilient and eternal structure of our religious, theological, philosophical and ethical heritage.

It reinforces a Christian hope of our values: those of a generous and hospitable society rooted in history; committed to the common good and solidarity in the present; creative, entrepreneurial, courageous, sustainable in our internal and external relations; and values that are a resilient steward of the hopes and joys of future generations in our country and around the world — hopes that are not exclusive, but for all. That is what our values have been when they are at their best.

Burke famously wrote that society is a “partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.”[1] He articulates an idea of loyalty:[2] loyalty to those who have sacrificed much in the past for us to be where we are; to our fellow citizens and to those whose lives will stem from our lives. Speaking of loyalty transforms the abstract idea of values — shared or otherwise — into relationships and practices.

In our schools, children are taught that Fundamental British Values are democracy; the rule of law; individual liberty; and mutual respect for and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs, and for those without faith.

These values — and our present situation — seem to be increasingly disconnected from our historic narratives, whatever the values of these Fundamental British Values are (and they are considerable), and they are not properly embedded in the heritage of our country.

Historians such as Diarmaid MacCulloch speak of religion being “a force that shaped the English soul”: to apply a revisionist secularism to our notions of identity inhibits the ability to reassert the ‘deep values’ reflected in our common history — those that show what makes for virtue, and of what is good in absolute and permanent terms. It is what Aslan in CS Lewis’ Narnia called the “deep magic” of the system.

It is in these deep values and loyalties that we find who we are — and by their change we see what we should be. Fundamental British Values have certainly developed out of these deep values; but if they are not grounded in an understanding of how we came to be who we are, they will remain an insubstantial vision with which to carry the weight of the challenges of the 21st Century.

That is because the right to life, liberty and the rule of law and robust democratic government does not come cheaply, nor is it held lightly. The roots of our freedom in this country are deeply embedded within our British constitutional and civic life because their foundation lies within the shared scriptural inheritance of all our faith traditions.

Democracy is not in and of itself the final answer to things; nor is the rule of law. Martin Luther King and Desmond Tutu did not accept the final authority of the rule of law when the law was unjust. Dietrich Bonhoeffer did not accept the final authority of the rule of law — democratically passed in a democratically elected assembly — over issues of German Jewish citizens when the law was manifestly evil.

We live in easier and happier times. But there is still debate over freedom of speech, and an increasingly anxious approach to tolerance. Alongside the nation’s seasonal debate about the true meaning of Christmas, we have seen questions return about the boundaries of free speech for Christians and those of other or no faith. Unsurprisingly, I’m very much in favour of speaking openly but sensitively — as the Prime Minister has both supported and done recently in her own workplace.

Our values are very deeply rooted, but are also necessarily continually reinterpreted — especially at times of change like now. That by itself is a huge challenge in the context of ever-increasing diversity, and of how we demonstrate the essential human dignity and equality of all human beings — regardless of gender, sexuality, ethnicity or ability. We know that we lack integration of newer communities, especially around issues of women’s rights, and of tolerance and respect for different views. Our failures in that area by themselves call on us to be clearer about our shared values.

Values are developed and refined above all in intermediate institutions, which is where democracy is founded, and our diversity preserved and nurtured for the common good. Noble Lord, Lord Harris, this morning in his Thought ForThe Day expounded this particularly powerfully and clearly.

My illustrious predecessor, Lord Williams of Oystermouth, made this point in a lecture in 2012. Archbishop Temple made it in Christianity and Social Order in 1942. Both Archbishops spoke of the decline of intermediate institutions in the face of an over-mighty state and of rampant individualism. Intermediate groups are where we build social capital, integrate, learn loyalties, practices and values, learn to disagree well — to build hope and resilience.

The most fundamental intermediate institution is the family: the base community of society. Companies are becoming intermediate communities,[3] so are clubs, charities, Near Neighbours groups and so on. Schools are key intermediate institutions, as the Revd Prelate the Bishop of Ely will describe. Intermediate institutions are repositories of practices and loyalties fundamental to who we are, even with their idiosyncrasies and untidiness.

The renewal of the values that will enable us to flourish in the post-Brexit world are not simply about us as individuals or the state as the arbiter of what is considered virtuous; but also require a renewal of intermediate institutions; because otherwise nothing stands between the lonely individual and the over-mighty state. As the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government recently said: Government “can build …homes… but alone can’t build communities… a sense of belonging or force people to love thy neighbour as thyself.”[4]

Our response to those who seek to threaten and undermine our values cannot simply be grounded in a defensive or preventative mind set. To draw back into ourselves. To look after our own. As part of the counter-radicalisation policy, ‘Prevent’ may be important. But if we spend all of our energy preventing bad ideologies — whether religious or political — I fear that we will neglect the far more transformative response required to build a convincing vision for our national life.

In short, we need a more beautiful and better common narrative that shapes and inspires us with a common purpose; a vaulting national ambition, not a sense of division and antagonism, both domestically and internationally.

We need a narrative that speaks to the world of bright hope and not mere optimism — let alone simple self-interest. That will enable us to play a powerful, hopeful and confident role in the world, resisting the turn inward that will leave us alone in the darkness, despairing and vulnerable.

We have seen this hope in our best developments as a nation, historically through advances in housing, public health and education. They were carried out by governments national and local; but they usually began with intermediate institutions — whether housing associations, local efforts to tackle poor hygiene and sewers or church schools[5]. At their heart they bring true integration, based on the God-given dignity of all human beings — whatever their ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability or economic worth.

A vision of this kind will promote cohesion around the common good. It will encourage courage and creativity. It will lead us to train young people in new skills. It will give us the strength to open new markets — to share our wealth and wisdom fairly and not only to our advantage. To welcome the alien and the stranger. It will challenge us to be consistent — to have an eye to our relationship with future generations, notwithstanding the events that intervene.

Such a vision has a deep magic that has, at our best, enabled us to be a country of hope and purpose — and will do so again.

We must now renew that hope and purpose, at every level of government and of our common life — and demonstrate it not only in our words but by embodying the values that make for a good society.

I beg to move the motion that stands in my name.

In his closing remarks, the Archbishop said:

My Lords… to sum up, the overall mood of the debate was hopeful and positive. There were marvellous contributions on the good things that are going on in our society. Rightly, a lot of noble Lords picked up on the life and example of Jo Cox, whom I am sure we will go on missing for many years.

I thought that the closing speech from the noble Baroness, Lady Sherlock, was particularly powerful and picked up in particular on issues of identity, to which I shall come back in a moment. Among the hopeful things was the affirmation of intermediate institutions, how they work and their contribution to our values, and the emphasis on shared values rather than British values. I agree with that very much — and the powerful exposition of that from the noble Lord, Lord Singh, will stay with me for a very long time. The noble Lord, Lord Paddick, and the noble and right reverend Lord, Lord Harries, picked up on that extremely effectively.

We heard many good and particular examples — and I especially mention that of the Armed Forces in the contribution of the noble Lord, Lord Dannatt. But concerns were also mentioned, above all that of inequality. Something we share right across the House is the sense that inequality can lead only to instability and extremism and to people being pushed into places they would never have thought of finding themselves.

There were concerns about the atmosphere after the referendum. The speech of the noble Lord, Lord Bilimoria, will also stick with me for a long time — a passionate declaration of what it is to belong to this country and yet find yourself at the wrong end of abuse. We will all feel a common sense of shame that that happened in this country. Concern was mentioned about post-truth and the sense that if you say something loud enough, it will be believed.

That links to the issue of social media and its continual abuse, particularly in the context of young people. Noble Lords talked about the mental health of young people and how they are victimised and marginalised, particularly over sexuality. I listened to the noble Lord, Lord Collins, with much attention and will reflect closely on what he said in a powerful, passionate and compelling speech.

A number of individual issues were raised as well, and underlying them one major question that we must go on discussing is that of values. I do not believe that values can be tidy; we do not end up with a single list to which we all affirm. Values are necessarily dynamic and constantly adjusting to the situations around us. The noble Lord, Lord Collins, made that point very powerfully. The word “inclusion” is a two-edged sword.

There have been celebrated and huge advances as a result of inclusion. The noble Lord, Lord Popat, and the noble Baroness, Lady Warsi, spoke of the massive contribution from communities that have come into this country in the past 40, 50, 60 or 70 years, and how they have transformed us for the better. We welcome that unreservedly.

But there is also, as the noble Baroness, Lady Buscombe, said very powerfully, the incommensurability of values — when there are two or many completely different ways in which to look at values, and we struggle to know how to deal with them. I was particularly grateful to the noble Baroness, Lady Sherlock, for raising the issue of “disagreeing well”, and how to develop that as a new value.

In the Church of England, we have not had a universally brilliant history of that, as my inbox today has already shown me. But it is something we have learned to do by coming together in carefully structured conversation, as happens particularly over LGBTIQ issues.

I close with something which was echoed around the House numerous times during the debate. We actually do not talk about values so much as practices. That was said by the noble Lord, Lord Glasman, and demonstrated by the noble Lord, Lord Crisp. When we look back at how we have demonstrated our values, one of the pre-eminent examples must be the work of the Labour Government after 1945. They demonstrated a change in values from the 1930s, coming out of the destruction of the war and bringing out the things that we wanted to be — the NHS and the implementation of the Beveridge report. If that is going to happen, we have to have confidence in what we are doing.

Inclusion can become an excuse for lack of confidence. We accept that everything is all right really, but it is not, of course, when you do that and you end up with the kind of problem that the noble Baroness, Lady Buscombe, was speaking of. There has to be a sense of identity, as was brought out powerfully by the noble Lord, Lord Popat.

The noble Baroness, Lady Sherlock, spoke of communitarianism. I will finish with a brief anecdote. A couple of weeks back, I heard a radio interview with a senior member of a parliament within Europe — I will not be too rude by being precise. When asked, “What about the Islamic community in your country?”, they replied, “There is no such thing. We do not do communities; we do the state and individuals.”

What that leaves you with is vulnerable individuals and an incapable state. We have to have the confidence to say, as has been said numerous times this afternoon, that we believe passionately in communities — we are communitarian — and if they clash, we will learn how to clash well. That is a value to which we will hold. I am extraordinarily grateful to all noble Lords who have been here and participated in this long debate.

Footnotes:

[1] Edmund Burke, Reflections on the French Revolution para 165

[2] This approach is much influenced by Julian Rivers’ article, ‘Fundamental British Values and the Virtues of Civic Loyalty’, published in Ethics in Brief, Summer 2016 (Vol. 21 №5) The Kirby Laing Institute for Christian Ethics

[3] Pope John Paul II on the definition of a business (paragraph 35 of Centesimus Annus): http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_01051991_centesimus-annus.htm

[4] Sajid Javid, keynote address at Church Commissioner Reception in the Jubilee Room, Houses of Parliament, 23 November 2016

[5] A Victorian priest said that if you love Jesus, you will care about drains