Criminal Justice Reforms In Mississippi Have Been Modest

The Naïve Notion that Mississippi has Comprehensively Reformed its Criminal Justice System

*originally published in Deep South Daily on Dec. 30, 2014.

2014 was a big year for criminal justice reform. It was a hot topic in the federal government, state governments, and national media. The ACLU received an unprecedented $50 million grant with the motivation to cut the number of incarcerated Americans in half by 2020. This wave of criminal justice awareness wasn’t limited to liberal or progressive states. In fact, Georgia and Texas were two of the leading examples looked to for enacting reforms. Mississippi joined this trend, and the broad sentencing reforms are commendable. However, it’s nothing more than naive optimism to believe that Mississippi has fixed a system in one year that has been broken for decades.

In March, Governor Phil Bryant signed into law a “comprehensive” criminal justice reform bill designed to reign in correctional costs, clarify sentencing guidelines, and encourage alternatives to prison for nonviolent offenses. The bill was informed by the December 2013 report issued by the Corrections and Criminal Justice Task Force. The sentencing guidelines for violent offenses and alternatives for nonviolent offenses were aimed to enhance public safety, but the primary motivation was fiscal. Nonetheless, the shortcomings of the reform package will be costly.

Mississippi’s criminal justice reform legislation of 2014 was hardly “comprehensive,” and the upcoming session should prioritize reforming aspects of the justice system that have been neglected thus far. Sentencing reform, however broad, is merely one of many aspects of our broken criminal justice system, and two recent controversies — the indictment of Corrections Commissioner Epps and the class action Sixth Amendment lawsuit in Scott County — illustrate the need for reform beyond sentencing.

The 49-count indictment of Epps is relevant for two reasons. First, it seriously impeaches the character and credibility of the longest serving Chief of Prisons in the state. In a letter to the Clarion-Ledger, he boasted, “the $41.12 per day cost of housing an inmate is one of the lowest in the country,” and it’s precisely that willingness to inadequately finance prisons that made him so popular with state lawmakers working with a limited budget. Secondly, the controversy allowed the deplorable conditions of Mississippi prisons to resurface. We know that our prisons are grotesquely inhumane because of federal DOJ investigations and constant litigation with civil rights organizations such as the Southern Poverty Law Center and the ACLU.

It’s concerning that we passed reforms to lessen the burden of a system that already is grossly underfunded. It appears that Mississippi couldn’t afford to continue incarcerating so many people at current costs, but it appears that current costs aren’t enough to operate a minimally humane and constitutional corrections system. We have to decide whether underfunded state prisons and privatized prisons concerned with profits are compatible with the moral standards of our state, and we have to decide whether to funnel more resources into the prisons or funnel money into federal litigation defending the indefensible.

Another recent controversy is the ACLU class action against the state for failing to uphold the Sixth Amendment right to counsel in Scott County. But it’s not just Scott County; there is practically no right to effective assistance of counsel in several local jurisdictions. Mississippi is one of the few states in the country that does not contribute any funding for indigent trial-level defense of noncapital crimes. Although the Supreme Court of the United States held in 1963 that the state is responsible for providing counsel, it is sufficient for the state to ensure that counties are providing indigent defendants with counsel. Clearly, local jurisdictions are not fulfilling this obligation, and the state’s failure violates the Sixth Amendment.

The Office of the State Public Defender was created in 2011 to survey public defender systems throughout the state and potentially advise the legislature on the creation of a statewide system. The Office of the State Public Defender released a report urging the state to address the patchwork public defender system in October 2013, and it appears to have been largely ignored, even though it was produced two months before the report of the Corrections and Criminal Justice Task Force that informed the reform bill. The State Public Defender, Leslie Lee, wrote a guest column in the Clarion-Ledger last April pointing out that the reform bill “left out public defenders.” She argued that judicial discretion for alternatives to incarceration won’t be individually advocated for without effective public defenders, and thus, “the governor’s well-intentioned reforms are at risk of failure.”

Not only are we unconstitutionally detaining citizens, but we are paying for citizens who haven’t been convicted of anything to sit in jails for months. This too will result in increasing litigation expenses.

The issue of locally funded public defense raises other concerns that have broader consequences. Most importantly, the county system is counterproductive. The 2013 report notes that communities with most arrests are also most in need of social programs. Thus, they have the least funding to spare for defense. Defendants in these jurisdictions will suffer more collateral consequences of arrests — having their jobs and families disrupted while they languish in jail without any social programs to assist them upon eventual release — further marginalizing them socioeconomically. That’s not just a cycle, but it’s a whirlpool. With each cycle in the criminal justice process, the chances of escape are lessened.

So, the local jurisdictions most in need of social programs, with at-risk characteristics, cannot support a public defender system. As I mentioned in a guest column in the Hattiesburg-American this summer, the bill did nothing to address collateral consequences. Optimally, every county would have a fully funded and effective public defender office that addresses these issues, but that’s clearly too much to ask for. Alternatively, a reform package should be passed to implement a statewide public defender system and legislatively remove these collateral consequences of arrest and conviction.

It is odd that the Corrections and Criminal Justice Task Force looked into variables related to recidivism, but collateral consequences were not mentioned. What about the effect on employment, housing, family, and licensing? When these aspects of someone’s life are disrupted, his ability to successfully avoid recidivism is reduced. By only encouraging alternatives to incarceration, it appears that we impulsively chose to fix the defendant rather than the system. Sure, there will be defendants who can benefit from substance abuse or mental health treatment, but they all would benefit from not having to check a box on job applications.

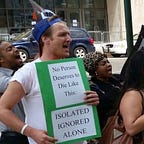

Our state has willfully ignored the unconstitutionality of our criminal system, and there is no reason to further delay the inevitable. Criminal justice reform is sweeping the nation, and failure to act will keep us behind. We can do better. A system this devoid of justice doesn’t serve public safety, but it uses tax dollars to maintain poverty. That poverty is unjust for the individual and a burden for the state. If neighboring states continue to pass meaningful reform, civil rights nonprofits will concentrate resources on our state, and federal intervention akin to the civil rights era will compel us to reform.

The explicit motivation of the reform bill being fiscal, the grossly underfunded prison system, and the failure to finance a statewide public defender system illustrate the political unwillingness for the state to invest in justice. We are compromising our moral and foundational ideals as long as our justice system sustains poverty and marginalization without a hint of due process. This perpetual injustice will disserve the general public and continue to burden the state. The Bill of Rights isn’t optional, and reform is unavoidable. Unfortunately, there will continue to be costly indefinite pretrial detention and costly federal litigation while we prolong truly comprehensive reform.