November 24, 2014: The Night Social Media Broke My Heart

*originally published in Deep South Daily on Nov. 28, 2014.

As 9 p.m. neared, I anxiously checked Twitter every couple of minutes for the announcement of whether the Grand Jury indicted Officer Darren Wilson. When I realized there was no indictment I shut down.

I tried to resume my studies, but I couldn’t. And after a couple unproductive hours, I did what anyone else would do; I logged onto Facebook. I was met with a newsfeed of friends sharing a Ted Nugent status: “Here’s the lessons from Ferguson America–Don’t let your kids grow up to be thugs…” One friend wrote, “Justice was served for Mike Brown by officer Darren Wilson.” I became enraged, but once I realized they weren’t outliers, I was heartbroken.

At first I wanted to think people just didn’t understand. Maybe they didn’t understand the nature of a grand jury deliberation. After all, several friends (believing themselves to be witty) were pathetically contrasting the community’s reaction to white people not rioting after OJ was acquitted. While such a comparison deserves little response, maybe they just didn’t understand that this was a probable cause determination — not a public, adversarial trial deciding guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Some people suggested the extensive testimony before the grand jury illustrated a thorough and fair process, even though expert commentators have described McCulloch’s strategy as odd, if not a clear indication that he was guiding the process to a predetermined outcome.

Whether or not they understood the purpose and procedure of grand juries, they clearly didn’t appreciate the context of the case. Within hours, people were contrasting the story to that of Gil Collar. Gil Collar was an 18-year-old white male shot by an African American campus police officer at the University of South Alabama in 2012. The facts of that case and this one are considerably different (There is surveillance footage of the nude, hallucinating student pursuing the retreating officer until he was within five-to-ten feet of the officer, at which point the officer fired one shot into his chest). To be clear, I do not support the police actions in either instance, and Gil Collar should have been subdued with nonlethal force His death, too, is a tragedy. However, the students of USA didn’t riot because that unfortunate event was hardly a manifestation of systemic injustice. The campus police were not systematically oppressing the student body. The media, for the most part, portrayed Collar as a good guy who made a mistake by experimenting with a dangerous drug.

One thing was indisputable — my friends were outraged. It didn’t matter if they understood the legal process or the context. Sure, I was discouraged by their supreme ignorance of privilege, but what broke my heart was that scores of friends who hadn’t made a peep about Mike Brown’s death since August were suddenly outraged by some burning buildings and cars.

My heart broke because my friends from Mississippi who offered any commentary were young white people deciding how Ferguson should react. They said, “the system is in place for a reason and it worked.” They said, “this country gives them freedom and they burn the flag?!” How could so many of my friends not realize that this community didn’t feel the freedom we feel? How could they not realize that the system works against this community?

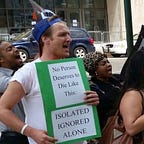

While people condemned the riots, I didn’t rebut with the typical “those are sensational images, but a lot of people are peaceful protestors.” I didn’t respond that peaceful protesters were going to be arrested and provoked by unnecessary force. Surprisingly to most, I accepted the riots as understandable. Maybe they aren’t reasonable, but they’re understandable. Of course riots aren’t preferable, but the community’s rage was absolutely understandable. I couldn’t imagine the pain of that community. As I mentioned in a previous column, this community is regulated and marginalized by the municipal courts the police inject them into, and now they’re faced with news that the local police can kill their unarmed children in the streets. I didn’t want to regurgitate the stats of racial bias in police encounters and arrests in Ferguson or the racial makeup of the police and local government in St. Louis County. I didn’t want to spout off the racial disproportionality in victims of police shootings. There’s nothing I could add that hasn’t been said.

What my friends decided the people of Ferguson should have done was either accept the decision or, at most, peacefully protest and engage in conversation. They ironically tossed around MLK references. Dr. King once said that “a riot is the language of the unheard,” and my friends were doing everything but listening. Over fifty years ago, Dr. King wrote that after attempts of peaceful advocacy are exhausted, people “will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat, but a fact of history.”

Civil Rights leaders knew this country was not made for black people. African Americans built this country and have died and marched to save its soul. I don’t want to strip communities of agency, but it’s not unreasonable to suggest that rioters felt like subordinates of Ferguson that night. In the heartbreaking video of Mike Brown’s mother reacting to the announcement of the grand jury decision, his stepfather screams “burn this bitch down.” That night, in that moment, I’m sure members of the community felt that they merely existed in a white man’s land. I’m sure a couple thought, “I’m tired of sporadic protests and demands for reform. That cycle has failed us again and again. That’s not working!”

Michael’s mother sobbed, “Everybody wants me to be calm… They still don’t care. They’re never gonna care.”

My heart broke because I knew that night would be a night my children will ask me about, like I ask my dad about the Civil Rights movement.

My dad was born in Newton, Mississippi in 1949. Years ago, when I asked him about that time, a time that we all acknowledge was unjust, he picked up on an implied question. He knew that his son wanted to know if his father was complicit with such gross injustice. He told me his parents had an absolute rule that the n-word was not allowed in their home. He told me that he remembers walking downtown and seeing a group of black kids turned away from a local business and how he thought, “that’s not right.” While I understand that people are the product of their times, his response didn’t make me proud. Sure, I was grateful that my dad wasn’t a racist, even though most were. But I don’t take pride in my dad thinking something that was wrong was wrong. I hope that my generation will do more. I want us to radically demand equal justice. Unfortunately, when my kids ask me about Mike Brown and the failure to prosecute Wilson, I will respond, “I thought, ‘that’s not right.’”