Oversimplifying Ferguson: The Problem is Bigger than the Police

*Originally published in Deep South Daily on Aug. 27, 2014.

HOW POOR BLACK MEN PERCEIVE LAW ENFORCEMENT IS FRAMED BY MORE THAN POLICE ENCOUNTERS: BROADER PERCEPTIONS OF THE JUSTICE SYSTEM HELD BY THOSE IT HAS FAILED

Much of the discussion surrounding Michael Brown being fatally shot by a police officer and the ongoing protests in Ferguson, Missouri has concerned perception — how communities of color perceive law enforcement, how law enforcement perceives black men, and ultimately how the media portrays and general public perceives young black men.

During a press conference on August 18, President Obama responded to a question about Ferguson, saying, “We’ve seen events in which there’s a gulf between community perceptions and law enforcement perceptions around the country.”

Typical discussions of race and the criminal justice system largely focus on the racial bias of police encounters, arrests, and incarceration. After all, nearly 93% of the arrests in Ferguson last year were of black people, although they make up 63% of the population. Empirically evidenced bias in these areas has informed our perception of the system, but it seems like we haven’t even begun to grasp the larger picture of perceived racial injustice.

To compound the racial injustice those statistics demonstrate, it has been reported that only 3 of the 53 police officers in Ferguson are black, but we continue to ignore the process between arrest and conviction and the demographics within the courthouse.

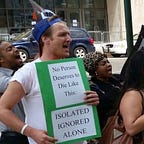

Photo by Tim Evanson

A community being policed by disproportionately white law enforcement is only one of many contributing factors, albeit a significant factor, resulting in their mistrust we frequently attribute to disproportionately black and brown men being frisked, handcuffed or worse — lying lifeless on the street after multiple gunshots or on the sidewalk after an unlawful chokehold.

When viewing the criminal system through a lens of racial justice, we should take issue with more than racially biased police encounters, excessive force and the diversity of local law enforcement. Police officers don’t just represent their department; they represent the law and have the power to inject someone into the criminal system. In other words, a community can feel wronged by local law enforcement for more than harassment or physical abuse. Police officers have the authority to arrest and detain citizens, initiating a burdensome process of fines, fees, warrants, and jail time.

Thomas Harvey, executive director and co-founder of Arch City Defenders, has linked the municipal court system with tensions in Ferguson. A recent paper he co-authored states, “Clients reported being jailed for the inability to pay fines, losing jobs and housing as result of the incarceration, being refused access to the Courts if they were with their children or other family members, and being mistreated by the bailiffs, prosecutors, clerks and judges in the courts.”

As the mayor of New York City recently said, “When a police officer comes to the decision that it’s time to arrest someone, that individual is obligated to submit to arrest…They will then have every opportunity for due process in our court system.” Thus, how a community perceives the criminal justice system is inextricably related to how it perceives the police. Who would want to submit to a police officer who he believes has unfairly come to the decision to arrest him, with the empty promise of due process in a court system he perceives as unfair?

For that reason, our discussion cannot be just about police reform. Legislators are beginning to take issue with mass incarceration, which is known to disproportionately affect young men of color. But I’m not just talking about sentencing reform. I’m not even just talking about criminal justice reform. I’m talking about racially conscious criminal justice reform.

Of course, I don’t think we should always avoid narrowly framed discussion or that we should discuss race abstractly, but these communities are oppressed throughout the entire criminal system. The racial bias and the race of the decision makers at each step, from police encounter to incarceration, surely contributes to how a poor person of color feels about the law and those who enforce it. A justice system with decision makers disproportionately made up of one race, disproportionately concerned with people of another race cannot be perceived as legitimate, much less fair. Such a system’s claim of “equal justice” is ridiculous.

To be clear, a fair system cannot exist with racial bias, but a fair system could theoretically exist with a monochromatic system of judges and prosecutors. Realistically, however, the criminal justice system will always be imperfect, and without diversity, it will never be perceived as legitimate. Such a system lacks the community’s consent.

Communities don’t protest when a white prosecutor and white judge control courtrooms filled with poor men of color, ultimately limiting their liberty and regulating their existence. If that were so, more than one city would be in a state of emergency. Nonetheless, the court’s role fuels the community’s mistrust that has culminated in protests around the country.

Although we know that less than 6% of the Ferguson police officers are black, we have not discussed similarly unrepresentative demographics in the prosecution and judiciary. Only 3 of the 20 Judges of St. Louis County Circuit Court are black. The other 17 Circuit Judges are White. Concerning the Ferguson Municipal Division, both judges are white. The Prosecuting Attorney of St. Louis County, Bob McCulloch is a white man whose father, mother, brother, uncle and cousin worked for the St. Louis Police Department.

Understandably, most courtroom dispositions are less provoking than an officer executing unarmed citizens in the street, but it’s important to realize the mistrust of police officers is a product of the accurately perceived racial injustices of the criminal system as a whole — including the whiteness of the opposing counsel and the bench.

Most people have witnessed a police-civilian encounter, but far fewer observe the proceedings of their local courthouses. While we understandably assume an officer without an audience of lawyers and judges, with low burdens of proof — reasonable suspicion and probable cause — is more prone to miscarry justice than courtroom actors, that dangerous assumption affords courtroom proceedings blind trust. Therefore, the injustices of our local criminal courts are more shielded from public criticism, and the injustice served is shrouded in formalism, civility, and a charade of fairness.

When the defendant is a poor black man, the inequalities of the criminal system become even more apparent. According to a 2013 study, public defenders in Missouri spend an average of nine hours preparing for serious felony cases for which they estimated to need 47 hours to prepare. For misdemeanors, two hours were spent out of the 12 needed.

Our discussions of perception have been rooted in the racial injustice of police misconduct and profiling. The racial disproportionality in our jails and prisons clearly illustrates how black men are perceived, and their awareness of this leads them to perceive society and law enforcement as people who consider them objects of fear. While racially biased police encounters and incarceration contribute to the tension between law enforcement and the communities they police, the process between arrest and incarceration and how the defendant and his family perceive that process is certainly relevant as well. A poor black man arrested by a white cop, given less than ethical representation by the State, in a courtroom filled with black men, dehumanized by a white prosecutor, before a white judge will hardly perceive the justice system to have integrity. Neither will his sons.

If both racially suspect statistics of law enforcement encounters and the demographics of local law enforcement are relevant to the community’s mistrust of police, the demographics of all major actors within the criminal justice system are relevant to the community’s mistrust of the criminal justice system. Before heavily policed communities can be expected to respect law enforcement, they must trust that equal justice is handed down in criminal courts — the courts police officers place them in.

To remedy the tension and mistrust we have to do more than take away the tanks and encourage more representative demographics in policemen. The less sensational debates concerning diversity on the bench, affirmative action in law schools, prosecutors striking black jurors, and implicit racial discrimination during trial and sentencing are components of the same story. It would have been inappropriate to jump into these related issues without first talking about the specific injustice of Mike Brown’s death, but a widespread acknowledgement and comprehensive solution to our country’s broken criminal system plagued by racial injustice won’t occur unless we begin to connect the dots.