Why Racial Injustice Persists in New York City, Mississippi, and Everywhere Between

*This essay was originally published in Deep South Daily on Aug. 5, 2014.

The following is a reader response to Zachary Breland’s opinion piece, “Mississippi is Still More Racist Than New York City.”

On May 25, Zachary Breland’s opinion column responding to the Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown episode covering Mississippi took the position that “targeted racism in the Deep South is still more potent than the ‘diverse’ racism of the Big Apple.” After spending the summer in New York as a legal intern determined to advocate for racial justice, I finally feel equipped to offer a credible response.

I completely agree with Mr. Breland’s statement that “for every account of overt racism that occurs, whether by individual or by hate group, there are 1,000 incidents of subtle racism, and innumerable challenges created by institutional racism.” I just wish this statement wasn’t glossed over in closing. This response largely expounds on this statement and argues that it was the most valuable statement of his column.

I grew up in Newton, Mississippi, a half-hour drive from the town where three civil rights activists were lynched during Freedom Summer. My dad was six years old when a teenage boy from Chicago visiting family in Mississippi was castrated, murdered, tied to a heap of metal and thrown in a river for allegedly flirting with a white woman.

A couple weeks ago, while sitting outside my office in the South Bronx, I read that four more white people from Brandon, Mississippi were indicted for racially motivated murders in Jackson. These stories evoke an emotional response for anyone with a soul, but they serve as distractions from the systemic injustice in every town and city in America. Breland wrote that he’s spent about as much time in New York City as Bourdain has in Mississippi, and they “both lack the exposure to make any definitive statements based on observational knowledge about the other’s home state.”

Of course, my summer in New York City doesn’t make me an expert, but the commute I’ve made nearly 100 times provided a powerful experience. For ten weeks, I have walked the same half-mile of East 161st Street, from Yankee Stadium to The Bronx Defenders. My first week I thought, This is everything I love about America! What’s more American than Yankee Stadium?

I lived in Queens, and experienced more diversity in my first week than I had in my life. For the Fourth of July, I gathered in a crowd of varying pigments and languages. I watched the fireworks while standing behind an interracial couple, one in a Brazil jersey and the other in a USA jersey. I thought I was going to spend my summer in the heart of progressive America. Soon, I realized my commute not only illustrated everything I love about America, but also everything I hate.

Most mornings I get on a crowded subway at Grand Central, but I usually get a seat once we’re north of 125th Street, after the white flight. On days I dressed casually I looked lost while walking from the 161st Street station — like I didn’t belong. Taxis would honk their horns more often than not, offering to rescue me from somewhere I didn’t belong. However, most days I wear a suit and walk unnoticed. In a sea of black and brown there are white lawyers in suits.

Last Wednesday, I walked past Court Deli as two men of color were being arrested. On Monday, as I walked past Administration of Child Services I witnessed a black mother shouting about their social workers snatching her child from her. Across the street, a young black woman was on the phone updating family and friends on a relative’s criminal case. This half-mile is the epitome of courts regulating poor people of color, and I feel dirty every day I walk between Yankee Stadium and the office.

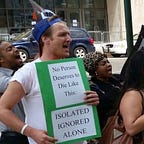

I’m the first to admit that Mississippi has a sinister legacy of racial injustice, but in many ways this injustice is felt for black men across the country. This is especially apparent as the world watches the viral videos of Eric Garner dying on the sidewalk of Staten Island while police stand around his lifeless body after administering an unlawful chokehold. When I became determined to advocate for racial justice, I quickly realized the need to consciously reserve “racism” for things like white kids targeting black men in Jackson to run over.

Too often we have to roll our eyes when people say, “I’m not racist, but…” or, “I have several black friends.” When my Criminal Law class covered racial disproportionality, a student exclaimed loudly, “What is the point of this? Are you asking us if we think the prosecutors are racist?!” That one word — racism — derails any meaningful conversation about race.

As long as racial injustice is couched in “racism,” we can pat ourselves on the back for not wearing pointy white hats or using racial slurs. White liberals in New York can ignore the line of black and brown people being bottlenecked into courthouses because New York isn’t as bad as Mississippi. White liberals in Mississippi can similarly ignore systemic racial injustice because they have a couple black friends and publicly decry overt racism. By focusing our conversations around explicit discrimination we perpetuate the status quo of implicit discrimination.

Both Mr. Bourdain and Breland made great points and provided meaningful insights, but our shared desire to finally sever our nation from its sinister racial legacy will require us to dig a little deeper than “racism.”

My emotional response to having my privilege thrown in my face each day this summer reminded me of me of the first time I was forced to acknowledge my unearned privileges. I spent two summers in Haiti working alongside people born into a life of predetermined hardships and hurdles, and the heartache of knowing they would never be able to board a plane — like I did — to leave that often cruel island is what motivated me to fiercely advocate for human rights. My worldview was clouded by the sensationalized “otherness” of the developing world, but in law school I realized the social injustice people of color endure daily in the United States.

Mississippi isn’t the greatest place for a poor black man–much less one accused of a crime–, but in many ways, the South Bronx, Mississippi, and everywhere in between can be a “cruel island” for people of color. Our complacency perpetuates their suffering, and tunnel vision on “racism” perpetuates our complacency.