Why Welfare Resentment Laws Will Only Expand Welfare

*Originally published in Deep South Daily on Aug. 21, 2014.

MISSISSIPPI’S LAW REQUIRING DRUG TESTING FOR WELFARE COULD HAVE THE PARADOXICAL EFFECT OF RAISING THE STATE’S WELFARE COSTS.

Mississippi’s welfare drug-testing law unfortunately went into effect August 1.

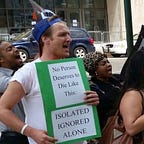

All too often I come across a meme on my Facebook newsfeed reading something along the lines of, “Shouldn’t you have to pass a urine test to collect a welfare check, since I have to pass one to earn it for you?” This is an example of the timeless phenomenon of members of the lower-middle class separating themselves from members of the “lower class.” Politicians have used disinformation and exploited the human desire to be “above” another group to manipulate the middle class into resenting poor welfare recipients.

Of course, well-spoken politicians mask the intention of reducing the number of “welfare checks” hard working, blue collar Mississippians are forced to fund. As The Clarion-Ledger reported in late July, “Phil Bryant, who supported the legislation, said it is a safety net for families in need, and adding the screening process will aid adults trapped in a dependency lifestyle so they can better provide for their children.”

First of all, I’m not sure pre-screening will aid anyone, as evidenced by the failed policy in other states. In Florida, 108 tested positive, but state records established that the cost of the program outweighed the savings. Virginia considered this policy in 2012, but the program that proposed a savings of $229,000 did not justify its estimated cost of $1.5 million.

Furthermore, Florida’s procedure did not involve pre-screening but mandated all applicants be tested, and that process has been held unconstitutional.

Other states, on the other hand, have implemented laws similar to Mississippi’s, and their results are negligible. After one year of screening in Utah, only 12 people — less than one percent of applicants — tested positive. Tennessee’s similar law went into effect last month, and of the 812 welfare applicants, only one person tested positive — compared to the 8 percent of Tennessee residents estimated to use illegal drugs. Which brings me to my second point.

Secondly, I believe Mr. Bryant means that it will “aid” a certain subpopulation of drug using adults. Wealthy parents have autonomy, while poor parents of color don’t.

I grew up in relatively privileged, white social circle in Mississippi. Many of my friends had alcoholic parents, and a handful of friends had at least one parent who used illicit drugs recreationally. In June of 2011 the New York Post ran an article, “NYC Moms Smoking Pot to Unwind.” Some of the moms particularly liked that the high wears off more quickly than an alcohol “buzz,” making it the perfect after lunch indulgence before picking kids up from school. Of course, Mississippi isn’t New York, but parallels do exist. What is the profile of a Mississippi mother “trapped in a dependency lifestyle” who needs state intervention to “better provide for [her] children”?

If a child’s parent is identified as a drug user, who will pay for treatment, which is much more expensive than TANF? If a single mother is deemed unfit because of her occasional drug use and/or her inability to care for her children without TANF income, at what point will that become parental neglect or abuse? Who will pay the social worker to take her children away? Who will pay for the state to “raise” the child? These questions illustrate the slippery slope of this law, and those same resentful, misguided middle class Mississippians who wanted to decrease “welfare” costs will front the bill.

This drug screening policy will perpetuate the costly and unjust cycle of regulating poor families. To put it simply, screening TANF recipients and applicants will have one of two outcomes. It could waste money because the expense of performing the drug tests outweighs the savings from reduced TANF recipients. Alternatively, it will drastically increase “the welfare state” by further regulating poor people of color.

Mississippi recently passed criminal sentencing reform, which was largely motivated from the expense of incarcerating so many people convicted of minor drug crimes. Incarceration is an extreme example of regulation, but probation and drug courts are still regulation by the criminal system. Coercing poor people into treatment is still regulation. While we decrease the extent of criminal justice regulations, we are potentially increasing our regulation in noncriminal arenas. Needless to say, regulating people costs money whether courts are involved or not.