Hate and Lovecraft

I was first introduced to H.P. Lovecraft by Metallica’s Call of Ktulu (embedded below). At the time, I had no idea the eight minute long thrash metal epic was based on, of all things, a short story (novella?) from an obscure author from the early twentieth century. Given my interests, however, it was inevitable that my path would lead me to that dread country of non — Euclidean nightmares and disgusting foul beings from beyond the stars that was Lovecraft’s body of work.

From an early age, I’d enjoyed reading fantasy. I finished reading the Lord of the Rings trilogy in my teens, and even though I’d never even held a d20 (that’s twenty sided dice for you normal folk) I absolutely devoured any and all books set in the Forgotten Realms. Fantasy was a quick jump to Sci — Fi and Horror, and after I’d finished reading Stephen King’s It I cast around for another horror writer to try out.

And Lovecraft ensnared me. At the time, I didn’t know what it was that made me feel incredibly excited for the ancient beings beyond the stars and monsters so impossible they drove men insane just by looking at them. I just liked it because it was so unlike anything I’d read before. Also there was this feeling I got, achieved by Lovecraft’s writing, of delving deeper and deeper into a fearful secret, a slow burn of dread and fear that you didn’t get from a lot of horror. That was, and still is, an amazing effect to me. I’ve never read anything like it before or since.

I have a few Cthulhu Mythos books in my collection, the pages browned and yellowed, well thumbed through, almost falling out of the book’s spine. They look, I imagine, much like what the Necronomicon from the Mythos must look like — ancient tomes of incredible and terrible knowledge, hiding dark horrors within their pages. Every now and again I go off and read a story from one of them, losing myself in the twisted corridors of terror which, sadly, now are so overly familiar to me that their terror have lessened somewhat. Even so, just the feel of the ancient paper, the ancient parchment, under my thumb as my eyes scan the words puts me back in the days when my echoing footsteps first rang in the eldritch halls of Lovecraft’s imagination.

For those not in the know, Howard Philips Lovecraft was an early twentieth century American writer. His genre is known as either ‘Cosmic Horror’ or ‘Weird Fiction’, and he is known as a pioneer of both of those genres. The greatest body of his work was produced in Providence, Rhode Island, in the Roaring Twenties — fully a hundred years ago, now that I think about it. Works that he is most known for include ‘The Call of Cthulhu’, ‘At the Mountains of Madness’ and ‘The Shadow Over Innsmouth’. His most famous creation is Cthulhu, an ‘eldritch being’ as it were, from beyond the stars. While he created the Cthulhu Mythos, he did not call it that, and in fact the term was coined by August Derleth who expanded upon his ideas much later.

Lovecraft’s writing, in a word, is evocative. As in, it tends to evoke certain feelings. Like many writers of the period, their style is more narrative and descriptive, using words much the same way an oil painter would use their brush and pigments, as opposed to the modern style which tends to try and recreate the feeling of watching a film through a camera lens. For Lovecraft, nothing was more important than that his readers grasp a feeling, and so he creates a sort of baroque gothic atmosphere throughout his work, greatly exaggerating the shadows, the darkness, the fear and the madness felt by his characters. The central theme of his work is, in essence, ‘Ignorance is Bliss’, in the scientific sense. His most famous stories abound with scientists who seek to find out more about the human condition, learning more than they bargained for, and suffering madness after learning that which man was not meant to know. This is apparent in ‘At the Mountains of Madness’, where a group of scientists travel to Antarctica only to discover…well. That which man was not meant to know.

And yet there is another theme, one which while understandable, considering who Lovecraft was, when he lived and the society in which he lived in, and yet as alien to our time and culture as Nyarlathotep, the Crawling Chaos is to humanity. If I said it, you probably wouldn’t be surprised — Lovecraft was incredibly racist.

Like I said. A white American in the New England area in the 1920s, racist? Next you’ll tell me water is wet. Back then the N-word was probably just how they referred to African Americans. It’s what Lovecraft named his cat, in fact. Lynchings were things you brought your kids out to see. No, it is not acceptable, but back then, that was the prevailing attitude. So it’s unsurprising that Lovecraft would hold the same values. What would actually be surprising is to find a white American in New England in the 1920s that actively opposed segregation and racism. Now that’s a unicorn. As in, they don’t exist.

Now, how do we know about Lovecraft’s beliefs? Like all writers from a hundred years ago, what we know of them we know through their writing, and thus we know of Lovecraft’s racism through his writing. Yes, unfortunate as it is, Lovecraft’s canon of work is full of hatred. There’s some clever wordplay there that I’m too dumb to make. But it isn’t the kind of hate that you’d find spewed at you from under a MAGA hat or from a random part of the internet. This is the kind of hatred you find when you dig deep into someone’s soul. As I mentioned, Lovecraft was good at creating an atmosphere of fear and terror, and when you analyse certain recurring themes and literary devices Lovecraft used, you find that the source of this fear has to do with his prejudices, and his views on certain ah, ‘kinds of people’, as someone from his background might say.

The clearest example of this is in the story Arthur Jermyn. The story concerns a man, a gentleman, whose reputation is in dire need of repair. Having descended from an anthropologist specialising in trips to the African continent, he invites several other gentlemen to review his ancestor’s exploits. Unfortunately, this very investigation called into question the titular character’s own bloodline, and thus it was that Arthur Jermyn committed suicide (another major trope appearing in Lovecraft’s works). The major source of the fear, in this case, lies in Arthur Jermyn learning about his true parentage — in other words, the fear in this story is fear of miscegenation. The parallels are clear, and not to be repeated here (I won’t be responsible for spreading any more hatred than I already do to certain people). The same theme is included in The Shadow Over Innsmouth, and in The Call of Cthulhu there are many references to certain natives chanting in their ‘horrible’ language. Young as I was, these things flew over my head. Now they stare me in the face.

The question now becomes how to reconcile my love for the mythos and the incredibly awful person that the author was. If I continued to express love for the mythos, I could be construed as someone who agrees with his views, for those views were in fact expressed in Lovecraft’s work. I don’t want that — the last thing I need is to be viewed as a racist when I myself am at risk of racism. In fact, I was once verbally harassed so bad I broke down one day, but thankfully things didn’t escalate physically. And yet, despite the ugliness in the racism contained within his writing, I loved almost every other aspect of it. The way he entices the reader to the inevitable end, for example. The way he furnishes the mood to be one of dread. The incredible imagination in which he creates his monsters and creatures from beyond. These are the good parts of his work, which I still enjoy.

Is it possible to push past the racism and enjoy the work’s redeeming qualities? It would have been easier if the author’s beliefs were not baked into the canon, but that’s incredibly rare — when we write, we put a bit of ourselves into it, so any prejudice is often dug up and put on display there. In modern times, there have been attempts to remove the racism of Lovecraftian Horror and shift the focus on the better aspects of the Cthulhu Mythos. The tabletop game series Arkham Horror, for example, has many Asian, African and Native American characters who are, incredibly, more than their stereotypes. A lot of women also exist in non — traditional roles, without their genders being called out specifically. The focus instead is on the investigative portion of the mythos — on digging up the awful secret that Mankind Was Not Meant To Know. It also focuses on being in the roaring 20s, sans racism, a strange 1920s America in which race mattered less than it does in the 2020s. Then there is the show Lovecraft Country, which does feature racism as a theme but admirably does not promote it, instead it vilifies it, by having its main cast be black. The theme of racism, then, is not as hard baked into the Cthulhu Mythos as we might believe.

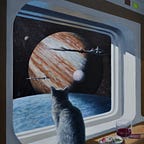

One of Lovecraft’s most enduring creations aren’t the racist depictions of non — White American natives of other nations, but rather the strange aliens from ‘beyond the stars’ such as Cthulhu, Nyarlathotep and Azathoth. Indeed, another name for Lovecraftian horror is ‘Cosmic Horror’, which feeds on the inherent existential nihilism when the scope of the universe is revealed and mankind’s role in it diminished to that of a speck of dust. As far as I can tell, there is nothing inherently racist here. Modern nihilists in fact point out to the vastness of space, string theory and the multidimensional theory (the last one largely due to Rick and Morty) to point out the futility of existence and any and all actions done during said existence, and nobody has ever accused that philosophy of being racist. Perhaps it’s possible to cherry pick Lovecraft’s creations and enjoy Cosmic Horror free from its author’s original racist trappings.

To come to a conclusion to this conundrum requires a smarter person than I. Perhaps it’s all right to be ambivalent to a work — praising it for its creativity whilst also condemning its author’s misguided beliefs. It is certainly a tangled issue, and one that despite all that I’ve said on the topic, is one that I haven’t managed to unravel. Maybe it’s simple — you like it, you’re racist, and you’re a bad person. Maybe it’s not. My experience with issues like this is that there’s always a more nuanced way of seeing things than just a religiously zealous application of values and painting things in black and white. We pride ourselves on our intellect, value discussion and accept as many viewpoints as possible (save for those that impinge on our ability to do so, of course), so hopefully we don’t just lazily slap labels on stuff and call it a day.

Lovecraft deserves hate, having held these ideas that have caused so much misery for so many. This is not up for debate. Whether his work deserves the same treatment, however, is something I think deserves some examination. Are the sins of the author the sins of the work, and are fans of the work guilty of the same sin? If we knew that we are, to misquote Lovecraft himself from the aforementioned Arthur Jermyn story:

“…we should do as Sir Arthur Jermyn did; and Arthur Jermyn soaked himself in oil and set fire to his clothing one night.”

Lovecraft feared that his humanity would be eroded by people like me. I cannot say that I do not fear the same thing; that my own humanity would be eroded if I learned I were anything like him. Perhaps Arthur Jermyn had the right idea, if for the wrong reason. Perhaps we should all set fire to the world and leave it to our betters, those unfathomable aliens from beyond the stars whose very visage would drive the best of us to madness.

At least they’re not racist.