The Unbearable Whiteness of Being

- White Space

One of the first things actors learn in their training is that every character must have a relationship to any space they enter. Is the space familiar or unfamiliar? Safe or dangerous? Beloved? Despised? Gendered? Forbidden? Can your character move about the space freely or do they need permission? In the presence of others, how much of a given space can your character claim for themselves? And how does that change when a new character enters?| In life, these are largely unconscious calculations we all make with the spaces we encounter and the people within them.

In the Age of COVID, those of us who are privileged to live in safe and peaceful communities have experienced for probably the first time in our lives what it means to have public spaces feel unsafe, even dangerous. The simple act of taking public transit or buying groceries has become fraught with stress and risk. Even walking down the street, we’ve learned what it’s like to feel a twinge of unease or even a threat to our well-being when a stranger comes within six feet of us. After barely two months of living like this, many have had it. Some took up arms to demand they be set free.

The reality we must confront now as a society is that the oppression and fear we all felt under COVID lockdown is a fraction of what Black and Indigenous people — and women of all races — are made to feel every minute of every day in the public and cultural spaces of our cities and towns, spaces that can rightfully be called, “white space.” Here is an excellent paper on the subject by Elijah Anderson: https://sociology.yale.edu/sites/default/files/pages_from_sre-11_rev5_printer_files.pdf

As we have seen in just the past few months with George Floyd, Christian Cooper, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor in the US and Regis Korchinski-Paquet in Canada, there are literally no safe spaces for Black people in N. America, not even in their own homes. A Black man can hope that a public street or park is a safe and neutral space where he can jog or watch birds, but as soon as a white person enters the scene, the space becomes potentially unsafe to him, even lethally so. This is what we saw happen to Ahmaud Arbery. This is what we saw Amy Cooper threaten to do to Christian Cooper. She threatened to turn what should be a safe and neutral space for the enjoyment of all into a hostile and potentially deadly space for a Black man.

The horrific deaths of Breonna Taylor in Louisville and Regis Korchinski-Paquet in Toronto show us that even a Black person’s own home is not a safe space for them. Breonna Taylor was sleeping in her bed when she was shot by police. We don’t know at present if Regis Korchinski-Paquet was thrown off her balcony to her death, but what we do know unequivocally is that her apartment became a lethally unsafe space for her within two minutes of the police entering.

The reality is equally as grim for Indigenous people in Canada: in a ten-day span in April the Winnipeg police shot and killed three Indigenous people, including Eishia Hudson, a sixteen-year-old girl. As I write this, |I am learning that police in New Brunswick have shot and killed Chantal Moore, a young mother, during what was supposed to be a “wellness check” at her home. While Indigenous people are just 5% of Canada’s population, 25% of all homicide victims are Indigenous, and over 30% of those killed by police are Indigenous.

The past twelve days, millions upon millions of us around the world have taken to the streets or added our voices in protest to condemn this police brutality and violence against two of our most vulnerable communities. As we transition now from protesting the injustice we don’t want to actualizing the change we do want, we have to confront and solve the fundamental injustice of physical and cultural spaces in our countries where people of color routinely suffer microaggression, physical violence, and murder.

Many white people will take offence at the suggestion that public or cultural space — or any space for that matter — is understood to be white. One common argument is that it’s not just whites any more who enjoy freedom and privilege in these spaces. There are high income, high status Asians like me and people of all colours who occupy supposedly white public spaces and cultural institutions without incident.

White space remains the most fitting term, however, because the freedom and privilege that non-whites enjoy in white space is only honorary and contingent. It can be taken away when it is convenient for white people to do so. Asian Americans and Canadians, for instance, have been hailed as hard-working, law-abiding, model minorities. That didn’t stop the interment of Japanese Americans and Canadians and confiscation of their land and property during World War II. It didn’t stop the auto industry Japan-bashing of the 1980’s (which led to the beating death of a Chinese American), or the anti-Asian hate crimes of the past few months (up sharply in the Age of COVID).

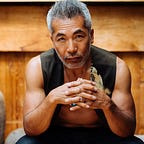

Or take Colin Kaepernick. Like elite athletes and entertainers of all races, he was granted access to a white cultural space and was an NFL star at its most prestigious, traditionally-white position. But when he asserted his support for Black civil rights in a way that offended the white sensibilities of the NFL shield, he was banished from the fold and has not returned to the field since. On a much less prominent level, I live a privileged and entitled life as an Asian actor and playwright. There is no denying though, that film, television and theatre in North America remain white cultural spaces. Unfortunately and insidiously, there have been instances in my career, too, when I spoke out about discrimination, only to have the message communicated to me that people in positions of power did not appreciate what I had to say.

To be sure, many public and cultural spaces discriminate against white people as well as people of colour. If you’re white but poor or homeless, if you are elderly, if you have a disability, if you’re a recent immigrant, if you wear certain markers of religious affiliation, if you are a woman, and so on, white space can be hostile to you, despite your whiteness. All of this is true. It is also true that only for Black and Indigenous people is white space routinely hostile to the point of murder. The killing has been so normalized, in fact, and we are so inured to this violence, that only the absolute horror and heinousness of George Floyd’s death has prompted, finally, a mass societal action against it.

And action we must take. How can we ensure the safety and human dignity of our most vulnerable and targeted communities in their interactions with police or any figureheads of authority? How can we ensure that Black and Indigenous people today are not excluded from the freedom, privilege and affluence our societies enjoy, societies built on Indigenous lands and the blood of Black slaves and Indigenous ancestors? These are the questions we need to ask. These are the conversations we need to have. Not just at the level of government and media town halls, but in our work spaces, our schools, our cultural institutions, our neighbourhoods. These are conversations for every home, every family, every couple, every group of friends.

This last point was brought home to my wife and I only a few days ago. As protests spread across America and the world, we were touched by two events in the seemingly bucolic Tri-Cities suburbs of Vancouver, BC where we live. We learned that a Black friend, a respected member of our community, had been accosted by an RCMP officer. The officer unsnapped the safety strap on his holster, approached my friend’s car with his hand on his weapon, and angrily demanded to know what my friend was doing in the area. At the time, my friend was getting his mail from his own mailbox at the end of his own driveway.

The next day, my wife’s prominence as a local Indigenous activist brought her in contact with the personal tragedy of a local Indigenous family, a tragedy entirely rooted in the hostility of white space toward Indigenous people and the erasure of Indigenous identity and culture from the national life of our country. When my wife posted her feelings of outrage on social media, she was predictably attacked by expressions of what can only be described as “white fragility.”

2. White Guilt, White Fragility

You don’t have to be white to be triggered by an accusation. We all experience feelings of indignation if someone says something about us that we think is unfair. We also all know what it’s like to strike back at a perceived slight with mock outrage. Mock outrage. Because once we’ve calmed down, a little self-reflection often reveals that our anger was not righteous; it was born of a guilty conscience.

This white fragility born of a white guilty conscience is a major impediment to dismantling the injustice and inequality in American and Canadian societies today. Can it be solved? I submit to you that the Japanese American and Canadian experiences hold a clue as to how the collective white guilt of our societies can be eliminated. Consider that just in the span of my lifetime, the Japanese on this continent have gone from despised, sub-human Other to respected honorary members of the club of whiteness. With that transition, white guilt over the injustice of the Japanese internment has subsided. In the past it was commonplace for white people to try to justify why the internment was necessary or merely an unfortunate consequence of war. In recent years though, there is a willingness, an eagerness to face the Japanese internment head-on in books and plays and tv shows. The history no longer evokes white guilt. Why not?

The Japanese internment has a happy ending: 1) It largely ended with the war (although Japanese Canadians were not allowed back to the West Coast of Canada until 1949). 2) In the U.S. some of the land, homes, and property stolen from Japanese Americans was returned. (Again, the Japanese Canadian experience was harsher — none of their land or property was returned). 3) Formal apologies were made in both countries, and reparations, though modest, were paid. Today, Japanese Americans and Canadians are a well-assimilated, high-income minority. We have been rewarded for our success and cooperation by being granted honorary membership into the club of whiteness. White society, meanwhile, can hold up the Japanese Americans and Canadians as proof that white society is no longer racist. White guilt over the internment is thus assuaged.

Let’s leave aside for a moment the question of whether Black and Indigenous communities at large would accept a similar arrangement even if it was offered to them. Let’s focus first on the inescapable truth that we are nowhere near being rid of white guilt as it pertains to Black and Indigenous people because these groups are the source of the “original sin” on which both America and Canada were founded. The guilt over this original sin has never been expunged or even addressed for the following reasons: 1) Meaningful apologies have never been made and reparations have never been paid. 2) What was stolen has never been returned. 3) The crime is still in progress.

Yes, the theft of Indigenous land and culture and the oppression and murder of Black and Indigenous people is still happening. This is not some mythic “original sin” from the mists of history. This is an ongoing crime, a lived reality in the present, and our societies cannot atone for a crime we are still in the process of committing.

To those white people who will not accept this and who are outraged by the suggestion: Why? The very fact that you think you can deny or discount the lived experience of millions of people of colour is proof of your white privilege. Your outrage is proof of your fragility, fragility which you then foist on people of colour by accusing them of being over-sensitive or of exaggerating the brutalizing harm of centuries of racist acts and racist spaces.

Returning to the issue of whether Black and Indigenous people could ever have a relationship to white society similar to what Japanese Americans and Canadians have — this is not a question for me to answer. The Black and Indigenous communities will decide for themselves what is just. What apology or reparations would begin to heal the wounds? What could be returned of what was stolen? But before we even get there, when will the oppression and killing actually stop?

To my Black and Indigenous friends and friends of all colors: we know that the vast majority of white people are our allies in this quest to overturn centuries of wrong. We know who they are. When we speak to them about injustice, they are not offended and indignant. They do not retort with what-about-isms. They do not white-splain and man-splain to us the reasons why we are wrong. Our white friends and allies listen. They speak out for us. They advocate for us and march with us. This week I have seen them lay their bodies down in the street by the thousands to grieve with their Black brothers and sisters. I have at times added my voice in unison. But I have also crossed an invisible boundary to watch this all unfold from the privileged space of my honorary whiteness. I have gone across that boundary time and time again throughout my life and in writing this essay.

This is the unbearable whiteness of being that I and many people of color and many white people, too, live with every day. When we see injustice and social and economic inequity against people like us or a shade darker, we have to overcome the white privilege in our own hearts which tells us we are entitled to turn away. We have to overcome the white privilege which gives us permission to enjoy the peace and freedom and affluence of our lives as if we earned these things, as if they are available to all.

They are not. We must not turn away. Privilege is not freedom, and our guilt is our oppression.