The Treasure Fleet That Disappeared from History

China’s forgotten naval supremacy

Under the Ming Dynasty, Admiral Zheng He of China went on seven maritime expeditions between 1403 and 1433. His fleet included about 250 ships, with 62 of those being treasure ships. The combined crew totaled just over 27,000 men.

Under the Ming Dynasty, Admiral Zheng He of China went on seven maritime expeditions between 1403 and 1433. His fleet included about 250 ships, with 62 of those being treasure ships. The combined crew totaled just over 27,000 men.

Tianxia, the Chinese cultural term meaning “all under heaven”, describes their philosophy. Tianxia is about civilization, politics, divinity, and is largely associated with Chinese nationalism. Due to this strong nationalistic identity, China ended up with many tributary states over the millennia. Many kingdoms they visited declared themselves tributaries to China, and these expeditions ultimately helped to interconnect countries and economies.

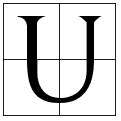

The above picture compares Columbus’s ship (Santa Maria) with a Chinese treasure ship coming in over 420 feet for size comparison. Also, mind that there were 62 of these treasure ships within the Chinese fleet. It could be said that China truly had the Mandate of Heaven.

Due to the size of the fleet, one can imagine that the Chinese were heavily militarized on these voyages. These excursions served two purposes. One, to demonstrate their power, wealth, and sovereignty (anybody who knew about China in this time period definitely did not doubt China’s sovereignty). Two, to amass even more tributary states. According to Tianxia and China’s nationalist views, tributary states are natural because of China’s sovereign and divine right to rule “all under heaven”. Over the course of Zheng He’s seven voyages from 1403–1433, China began obtaining a reputation as the dominant naval power in the East.

The Voyages

Over the course of seven voyages spanning over 30 years, Zheng He accomplished much. The first expedition was to the Western Ocean. Zheng He visited Champa, Java, Malacca, Ceylon, Calicut, and more. On their sail back to China in 1407, they fought with Chen Zuyi’s pirate fleet. Chen Zuyi dominated the maritime route of the Strait of Malacca and controlled trade. Using China’s naval prowess, Zheng He defeated Chen Zuyi’s pirate fleet and established an ally, Shi Jinqing, to secure access to the port for China.

During the third voyage, in 1411, the fleet stopped in Ceylon to confront King Alakeshvara of the Sinhalese, who the Chinese thought rude and hostile. King Alakeshvara posed a threat by committing piracy acts towards neighboring tributary states and controlled local waters. After docking, Zheng He traveled to Kotte with 2000 troops, where he was cut off by a surprise attack from King Alakeshvara’s army.

Zheng He’s men defeated the Sinhalese and proceeded to attack the Captial and capture King Alakeshvara along with his family and high officials. The fleet brought them back to China, where the Yongle Emperor freed them and returned them to Ceylon. The Yongle dethroned Alakeshvara and gave power to an ally, Parakramabahu VI. The treasure fleet had no hostile experiences from Ceylon after this point.

The fourth, fifth, and sixth voyages were to return ambassadors and officials to their home countries following celebrations in the capital, Nanjing. These expeditions gave safe passage to both officials and their treasured gifts from China and also allowed Zheng He to continue exploration conquests at the same time. These voyages led the fleet into Muslim countries and along with East Africa. After the fifth voyage, top officials from the fleet received gifts from the Ming court, including lions, giraffes, leopards, camels, zebras, rhinoceroses, ostriches, and other exotic animals.

Gone from History

Although the Ming treasure fleet established China as the dominant naval power in the East, all good things must come to an end. It is not completely agreed upon why these voyages stopped in the first place, however it is most likely due to multiple reasons. There was a hiatus of voyages between 1422 to 1430 because of several Chinese campaigns against the Mongols. The previous Yongle Emperor, a sponsor of the expeditions, died in 1424. The new Hongxi Emperor, however, was not a fan of the voyages. Some argue that the fleets were uneconomic and extremely costly to China’s treasury. Others argue that the fleet brought economic prosperity through new maritime trade. There was also growing fear of localized free trade as opposed to official government channels.

With a more conservative emperor now in power, the voyages eventually came to an end. High officials wanted to maintain foreign trade monopolies through government control, resulting in suppression of free trade along with the destruction of the treasure fleet. China so desperately wanted to control maritime trade that in the 1470s the government destroyed Zheng He’s logbooks so no such expeditions would ever be repeated. After the destruction of the fleets and logbooks, China effectively turned the great Ming dynasty Treasure Fleet into a fairy tale.

This sudden conservative, inward change in policy destroyed their naval power. Even in the 1400s, their ships and technology outpaced Europeans greatly. A single Chinese treasure ship made in the 1400s spanned over 420 feet while Columbus’s Santa Maria, built in 1460, was a mere 117 feet. In 1499, Vasco da Gama even heard rumors of giant ships in Calicut sailing around generations earlier in the Eastern seas. If China had continued to invest in its naval power, history may have gone in a very different direction.