Read the Archbishop of Canterbury’s House of Lords speech on education

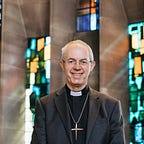

Archbishop Justin Welby led a debate in the House of Lords today on the role of education in building a flourishing and skilled society.

“The Lord Archbishop of Canterbury to move that this House takes note of the role of education in building a flourishing and skilled society.”

My Lords, I am grateful to the usual channels for making time once again for me to lead a debate in your Lordships’ House. It is now something of a tradition for an Archbishop’s debate to be held in early December. Though a little later and less well established than the John Lewis advert, the appearance of an Archbishop on the order paper is a sure sign that Christmas is just around the corner.

Last year, I led a debate on shared national values, which featured some extremely impressive and thoughtful speeches. I am sure that today’s debate will be equally impressive, and I am grateful to so many of your Lordships for making time to attend.

I look forward to your contributions, and it will be an especial pleasure to hear the first speech from the noble, reincarnated and Right Reverend Lord, Lord Chartres.

I am also delighted that the noble Lord, Lord Sacks, will be speaking today. He has told me — and obviously we all understand — that he will have to leave before the wind-up to get home in time for the Sabbath. But it is very good that he has come here at all.

There is a link between today’s debate on education and the previous one on shared values. What I hope to give today is an outline of the sort of values that we suggest, from these benches especially, should underpin our education system, and the structures that might support them, so that we might create a society where individual and mutual flourishing become the norm.

As in so many areas of our public life — if noble Lords will excuse a little bit of trumpet-blowing — it was the churches that pioneered the idea of a universal system of education, free for all.

In 1811, Joshua Watson founded the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales. Fortunately, our titles are shorter nowadays. The then Bishop of Oxford described Joshua Watson as “the best layman in England” — a title long overdue for revival: applications please in sealed envelopes to Lambeth Palace. What was started by Watson and others in 1811 lives on today as the National Society. I declare an interest as its co-president. My Right Reverend friend and colleague the Bishop of Ely, who I look forward to hearing speak later, chairs its council.

Watson set a values framework that was as important to the principles of free universal education as was the imperative — also in his ideas — to improve productivity and fight embedded squalor.

By 1870, there were too many children and schools for the churches to cope with alone, and the first of the great Education Acts brought the schools under state control, although still with a very strong religious participation from different Christian churches and Jewish groups.

Today, the Church of England alone educates over 1 million pupils each year in England, with 26% of all primary schools and 6% of all secondary schools.

Joshua Watson and his friends conceived their plans at a time of great national crisis and upheaval. The Luddite movement, which also began in 1811, was a response to fear of redundancy because of growing technological advances.

Two centuries later, the advances that threaten long — established patterns of work are different — but they are still there, in what we are now calling the fourth industrial revolution. As the World Economic Forum describes it, the digital revolution that has been occurring since the middle of the last century is today accompanied by emerging technological breakthroughs in fields such as artificial intelligence, robotics, the internet of things, autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage and quantum computing.

How our schools and our further and higher education institutions can equip us for this seismic shift, and how our systems of social security and support can enable us to keep our society cohesive and healthy, are among the greatest challenges facing this generation, and the generation to come. And, of course, there is Brexit, with unforeseeable changes, challenges and opportunities.

We need an educational system that can bear the weight of the changes that are coming. We must be sure that, while we might find some inspiration in our past, we do not waste our time rummaging there for the solutions of tomorrow.

We must also challenge anew the pockets of deprivation and underachievement that still exist across so many of our communities; and we must face the poverty of aspiration that so often comes with it, and which forms such a barrier to human flourishing in every form.

At its most basic, for the past two centuries the Church of England has looked to promote an education that allows children, young people and adults to live out Jesus’s promise of life in all its fullness.

That means enabling every person not only to grow in wisdom and to learn skills but to develop character and the spiritual, intellectual and emotional resources needed to live a good life, as an individual but also in a community.

In listening to a debate recently in your Lordships’ House about our science and innovation strategy, I was struck by an observation made from the Front Bench by the noble Lord, Lord Prior, who, echoing other speakers in that really extraordinarily good debate, said that,

“the cultural divide that we have had between academic and technical education has been a disaster for this country since 1944 and probably earlier”. — [Official Report, 23/10/17; col. 830.]

The truth is that the myths of a golden age or a disastrous misstep are both wide of the mark. The noble Lord went on to describe how our universities are some of the best in the world for academic achievement, but where we excel in research we often fail in development. The commitment to raise the UK’s spend on research and development from 1.7% of GDP to the OECD average of 2.4% is admirable and necessary — but, as the noble Lord pointed out, Germany already spends 3% and is aiming to spend 3.5%. This is an area in which we cannot fall further behind, but in which progress can happen only through the effective work of our education.

We have neglected the value of further education within our overall educational landscape for far too long, over numerous Governments and at least since the 1944 Education Act. That neglect is a legacy of the class system, especially in England. The children of privilege are continuing to inherit privilege and this is true not only in our educational institutions but the whole country.

It is also true globally, by the way, as seen in the USA and China. Unless we embark on cultural change, involving partnerships in education between businesses, local and national government and the entirety of our education services, I see little prospect of remedying this wrong. Human flourishing, and an opportunity for fullness of life for all those in education, requires flexible and imaginative training that is based on aptitude.

Our trend towards a more inclusive approach to those with disabilities or special educational needs is witness to the way that comprehensive education has improved, and is a welcome step towards an education that seeks the fullest and most abundant possible life for each human being, regardless of their ability — one which draws the best out of every person and leads them out into life.

But the academic selective approach to education, which prioritises separation as a necessary precondition for the nurture of excellence, makes a statement about the purpose of education that is contrary to the notion of the common good. At its best, education must be a process of shaping human beings to reach out for and enjoy abundant life, and to do so in such strong communities of widely varying ability, but distinctive approaches to each student, that they and all around them flourish. An approach that neglects those of lesser ability or, because of a misguided notion of “levelling out” does not give the fullest opportunity to those of highest ability, or does not enable all to develop a sense of community and mutuality, of love in action and of the fullness and abundance of life, will ultimately fail.

One area that I am most concerned about, which we on these Benches see most clearly through our parish system across the whole of England, and which was highlighted in Dame Louise Casey’s review into opportunity and social integration in December 2016, is how the handing down of poverty and deprivation between generations presents a barrier to achieving social cohesion as well as social justice.

Of those receiving free school meals, only 32% of girls and 28% of boys in the white British category achieve five A* to C grades at GCSE. That is third from bottom out of 18, above the Traveller and Gypsy/Roma communities.

One might conclude from this that white British children brought up in economic poverty stand a high chance of being among the least well-equipped to integrate into a rapidly changing world where skills in science, technology, numeracy, literacy and IT will be essential.

Not enough has been done to break down entrenched disadvantages or to improve integration and cohesion. The Church of England with its wide — and widening — schools network can and must do more to address this problem. This is the Joshua Watson challenge of our generation.

The aim of the founders of the National Society was to be universalist, unapologetically Christian in the nature of their vocation and service, and committed to the relief of disadvantage and deprivation wherever it was found. Ours must be the same. Two hundred years on, the role of the Church of England in education can be to encourage and support excellence and to provide a values-based education for all, with a laser-like focus on the poorest and most deprived. That means a renewed vision that focuses as much on deprivation of spirit and poverty of aspiration as did our forebears on material poverty and inequality.

What follows from that is a clear move towards schools that not only deliver academic excellence but have the boldness and vision to do so outside the boundaries of a selective system. The Church of England’s educational offer to our nation is church schools that are, in its own words, “deeply Christian”, nurturing the whole child — spiritually, emotionally, mentally as well as academically — yet welcoming the whole community.

I pay tribute to the immense hard work of heads, teachers, leadership teams, governors and parents associations who make so many church and other schools the successes that they are. With the strong Christian commitment of heads and leadership teams, the ethos and values of Church of England schools, which make them so appealing to families of all faiths and none, will be guarded and will continue.

A major obstacle, though, to our education system is a lack of clear internal and commonly held values. We live in a country where an overarching story which is the framework for explaining life has more or less disappeared. We have a world of unguided and competing narratives, where the only common factor is the inviolability of personal choice.

This means that, for schools that are not of a religious character, confidence in any personal sense of ultimate values has diminished. Utilitarianism rules, and skills move from being talents held for the common good, which we are entrusted with as benefits for all, to being personal possessions for our own advantage. We see this already in our universities, in the economic sword of Damocles that dangles over the heads of so many students who have vast financial investments at stake in their degree qualification.

The challenge is the weak, secular and functional narrative that successive Governments have sought to insert in the place of our historic Christian-based understanding, whether explicitly or implicitly. Functionalism or utilitarianism offers neither a meaningful alternative to those who are threatened by pedlars of extremism nor a confident framework within which to educate those of different cultures and beliefs.

It is no great surprise to those of us familiar with church schools — I should say that all five of our children went to state schools, both church and non-church — that their strong values-based approach remains so attractive, especially to communities of other faiths. Over the last 60 years, in many Church of England schools in areas of high immigration — although in some cases almost all the children are of a non-Christian faith — the narrative of the school has remained Christian while respecting religious diversity, including no faith at all.

Schools, FE and HE institutions are important intermediate institutions positioned between individuals and the state, which exist to bring fullness of life and to be nurseries of community living. As well as to inspire, they need to develop stories of the common good and of community, not merely of tolerance. This is achievable so long as our education system remains diverse in provision, but accountable and well-funded, enabling different streams and approaches within its overall ecosystem. Lifelong learning and training and developing the prestige of technical education are vital for giving us the flexibility and capacity necessary for the fourth industrial revolution.

The Church of England has recently set up the Church of England Foundation for Educational Leadership to begin to tackle the need for deeper and more effective training in issues of values and practices, as well as in the hard skills of leading schools and nurturing new leadership talent. Education must combine the provision of skills with the creation of values and practices that enable those values to be developed and to become virtues.

Where that happens, “life in all its fullness” becomes accessible to all young people. It is not a magic wand to solve all society’s problems, but it is an essential building block for achieving an education system that can help to build a more prosperous and cohesive society. I beg to move the Motion standing in my name on the Order Paper.