What could come next.

San Francisco elected a pro-housing mayor. Now what?

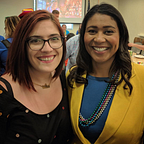

London Breed’s election as Mayor of San Francisco will define city politics for the next decade, with implications already resonating across the country. San Francisco exemplifies the modern housing crisis facing cities throughout the world. Cities everywhere will look to us for solutions— but only if we are successful in bringing down the cost of housing. San Francisco can transition from a cautionary tale to one of inspiration under the leadership of Mayor London Breed.

Breed has been incredibly honest about the solution to our housing woes. She has said it over and over: “We have to build more housing. We have to build more housing. We have to build more housing, and I will be relentless in my pursuit to get the job done.” She speaks boldly about taking pressure off struggling communities, and how building more housing will help cut our astronomical rents.

London’s experience and personal narrative are fundamental to tackling this challenge. She is a renter who lived with a roommate throughout her term as Supervisor. Our mayor grew up in public housing and has lived through a mass displacement crisis. And yet she speaks with hope and determination about making San Francisco a more affordable city, a city for all.

In her inauguration speech, Mayor Breed diagnosed the problem:

“We have people who come from all over the world, who come to create, who are innovative, who look at San Francisco and say that is the place where I want to be.

And we have failed. We have failed to build more housing to accommodate the increase in the number of job opportunities that have poured into San Francisco, pushing residents who have been here all their lives out of the city that they call home.”

And she’s right. San Francisco’s median home price is currently $1.3 million, according to Zillow; median rents are at $4,500 a month. In recent years, we’ve added eight jobs for every new housing unit and haven’t learned from our mistakes: We’re approving thousands of new jobs in areas like SoMa, without adding enough homes to absorb those drawn to our booming economy.

London Breed understands this mismatch. She’s written convincingly that we need “more housing at every level” — more affordable housing, more market-rate housing, more supportive housing for the homeless, all of it.

In the next hundred days, Mayor Breed will come up against that longstanding, ever-vigilant “no” that haunts the city bureaucracy. Our mayor will need help in the fights to come for these new politics of yes. Don’t kid yourself, this isn’t going to be easy.

So, where do we start?

Below are the policy prescriptions we think could be launched in the first hundred days. These are major steps forward. These five big ideas could be taken on in this first sprint, if we’re ready for big changes. This is just the beginning of what San Francisco is capable of. Let’s get to work!

1. Four Floors and Corner Stores

This is the wonderful motto for legalizing fourplexes citywide. The policy is being explored in Minneapolis and Seattle. San Francisco can eliminate exclusionary single-family-home-only zoning and create more residencies in our “residential” districts. We can start to modernize our code, getting closer to a form-based zoning code. The very un-sexy name for this would be “density decontrol.”

We already allow 40 foot high buildings in almost every neighborhood, but tragically we limit the number of families that can live in those 40 feet. Four unit wood-frame, walk-up apartment buildings are often cheaper to build, but are currently prohibited from being built in about 75% of the city.

A unit-per-floor model is an opportunity to allow a family on every floor. More people in the neighborhoods will be good for our small businesses, adding both more foot traffic and more places for employees to live.

We could limit this policy to apply only on vacant lots, soft sites or on owner-occupied homes, where a longtime homeowner decides to build a little multifamily building on their own property. With a well-crafted policy, we can encourage the construction of new apartments and protect tenants in single-family homes from the risk of eviction.

2. Streamlining, Especially for Small Projects

Large projects hit all kinds of hiccups resulting in millions of dollars spent on lawyers, permit expeditors, carrying costs, unexpected fees… Unpredictability and delays are extremely expensive, and driving up costs. Missing middle housing is difficult to build under these circumstances. When we add lots of costs, only the highest end housing will get through that gauntlet.

We need smaller projects with lower margins built everywhere in our city. We need cheaper construction types, such as wood frame and modular, to get through this process. Especially in the outlying neighborhoods, we have to actually allow housing to be built in practice. Housing can’t just exist on paper.

In order to get housing built, we have to stop chopping it off at the knees. We can’t wait 10 years to get shovels in the ground. We need major process improvements, from pre-application to post-entitlement. Some cities have over-the-counter approval for everything 10 units or less, or even all housing. Even LA has by-right approvals for projects up to 49 units! The rules should be the rules. Ministerial approval ensures that if you follow the rules, you get your permits.

For small projects with narrow margins, a streamlined comprehensible process is the only way housing will get built. Delays and unpredictable outcomes are prohibitively expensive for low-margin housing, exactly the type we say we all want! We are often talking about one-time developers building on their own land. We need a process that works for non-experts.

Different departments with conflicting requirements frequently contribute to the unpredictability and delays. The Fire Department will tell you the meter reader needs to be in one place, while the Planning Department will tell you it needs to be somewhere else. And while the Office of Disability is in charge of critical accessibility issues, their decisions are often the most arbitrary and unpredictable of all! Every plan-checker is making their own calls, and rarely do these decisions stick from one day to the next, from one department to the next. A complete harmonization of the code is badly overdue.

Missing middle housing is often built without elaborate financing, and can be more resilient in a downturn. But it needs to be predictable, and will be put on hold when faced with arbitrary outcomes. It cannot have excessive cost overruns. When these projects end up needing many-thousand-dollar permit expediters, they don’t get built at the quantity and scale we need.

3. Upzone Transit Corridors

We need to allow more housing near existing transit stops and corridors. Almost everyone who said they didn’t like SB 827 said they liked the concept of housing near transit, but couldn’t get around some problem with the execution. We can gather all these objections, solicit new ones and quickly launch the “right kind” of transit-oriented up-zoning everyone was clamoring for.

Mid-rise (5–10 story) buildings make sense city-wide, because they’re cheaper than highrises, and they look beautiful next to all kinds of things! At some point we decided that neighborhoods needed to be monotonous, but variety in building type can make things more interesting and more diverse.

When we’re discussing transit oriented up-zonings, people often get very reasonably worried about existing tenants. There are lots of ways to ensure we embrace policies of development without displacement. If we’re unsure about a more holistic tenant protection program, we can reinforce the existing prohibitions on tearing down multifamily housing, restricting the program to soft-sites and owner-occupied housing.

San Francisco has made massive public investments in our transit system. It doesn’t make sense to ban apartments right next to BART stations. Let’s make sure this transit gets used by the greatest number of people possible.

4. Affordable Housing Overlay

There’s no neighborhood in San Francisco that is “inappropriate” for subsidized Affordable Housing. For projects to pencil, nonprofit Affordable Housing developers need to build larger buildings — usually 50 units or more per parcel. This is currently illegal in about 78% of the city. It has created a segregated city, where subsidized Affordable Housing is only built in a few dense neighborhoods. You should check out Candidate for Supervisor Sonja Trauss’s plan to change this.

Even if neighborhoods say they’re not ready for market-rate housing, we should allow Affordable Housing everywhere. We can pass a zoning overlay to make it legal to build 100% Affordable Housing on every residential lot in the city. By relaxing density and height restrictions for fully affordable projects, we could integrate our exclusionary neighborhoods.

5. Public Land should be prioritized for housing

Our government owns all kinds of land — and a lot of parking. From the school district to the MTA, a patchwork of different departments have surface parking lots. We could do so much better with this valuable public resource.

All government-owned land could be quickly re-zoned to allow for housing. This would give our city the ability to build housing for city workers, teachers, or mixed-income housing for all. We could do 50% subsidized Affordable Housing, looking at models like the Balboa Reservoir where they’re doing 1,500+ units of mixed-income housing on publicly owned land. At Balboa, the private developer partner is paying for about 33% of the Affordable Housing, and the rest is publicly funded, getting us so many more homes for people struggling to get by in this city. By putting together a market-rate developer with a non-profit Affordable Housing developer, we can often cross-subsidize to get more units of Affordable Housing on this kind of public land.

We could build public housing on this land. We could build private nonprofit subsidized Affordable Housing on this land. We could even build new rent controlled housing on this land! But we can’t build anything on it if we don’t zone it for housing.

We can do this. We have to do this. We must take pressure off existing tenants by building significantly more of every kind of housing. We must to move away from car-centric infrastructure and allow the mass production of housing without parking that will be transit-oriented. We must build dense, vibrant, integrated, walkable communities of opportunity for all. We must address our linked problems of escalating housing costs, lengthening commutes and worsening segregation as a city, a region and a state. We need new housing production alongside strong tenants protections, to ensure that we’re not displacing existing tenants while we race to bring down the overall cost of housing. These are achievable goals.

Entrenched interests will make a lot of noise about these exceptionally reasonable policies. But in order to make real progress in a short amount of time, housing has to be built and built quickly. The city is in crisis.

As our new Mayor said as she wrapped up her inauguration speech:

“I am hopeful. I am optimistic. I am excited about the future, about what we will accomplish because on this day we are committed to rolling up our sleeves and working together.”