“Just dig deeper into the data!” — Reflections on becoming a better data scientist

This is a story about how an excellent boss taught me an important lesson and helped me become a better data scientist. While there are many ways to improve your ‘hard skills’ this experience focusses more on how I learnt by example to become a much better ‘soft skills’ person.

As science is becoming more inter disciplinary, human beings from various domains are working together for the first time. Inadvertently, this causes friction and a lot of heartache — especially because scientists are not known for their ‘people skills’. A common source of this friction occurs between ‘computational’ people and ‘wet lab’ people. Today, I want to share one such story with the hope of showing you how a good advisor can even take friction like this and turn into a valuable teaching experience. The point is neither to shame nor blame people but instead to share an experience about problem solving. My hope is that when you go through a hard situation, you’ll perhaps remember this and come out with your sanity intact and spirits not completely deflated.

Okay that’s enough foreplay — let’s get to the good stuff.

A few months ago, a collaborator — lets call them X e-mailed me to ask for an update regarding some data we generated for our project. We exchanged a few e-mails with updates. Basically, we only had 2 replicates and both of them suggested different results. I summarized that what we have so far is quite inconclusive and in any case 2 replicates is never really enough for scientific publications. My recommendation was we just get a couple of more replicates before I make any serious conclusions. At this stage, X kind of lost their cool. I received a pretty nasty email telling me to look harder in the existing dataset. X said: ‘Since you haven’t taken part in all wet-lab steps, let me tell you that one experiment takes about 10 days (from seeding cells to the final library)’ and continued with a dramatic — ‘Just dig deeper into the data!’.

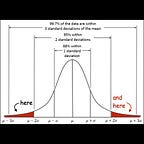

Now such e-mails although not ideal are unfortunately a part and parcel for many computational biologists today. The collaborator wants a magical answer without enough data and the statistician to be confident wants more than 1 or 2 replicates. This creates an impasse in which the biologist blames the statistican of having it easy and the statistician is now suddenly playing defense. Whenever anyone is playing defense, they automatically close off and their blinds go up to protect themselves — this is an evolutionary response which is extremely hard to change. The problem is this reaction serves no one and ultimately only spoils the situation further.

Funnily when I write about this incidence today, a bit removed from the situation, I realize that a calm response to such nonsense is ideal. But in the moment, this is much easier said than done. It was hard for me not to feel annoyed and a little angry about unfair expectations of X. Especially because such incidents had happened in the past also and we had spent significant time making sure the communication was more positive. In any case, I was disappointed and somewhat annoyed so I went to my boss to confer with him and ask him advice on how to best move forward. I was not sure how to move forward since with only a couple of replicates, its just hard to make any conclusions at all.

Now this is the part from which I learnt in this situation. My boss listened to the whole incident calmly and did not really show any annoyance at the collaborator (there is some history here so I was a bit surprised he didn’t react much at all). Instead, he probed me to more to understand what the larger question we were trying to solve was. Not in terms of what this particular experiment was meant to answer but the overall point we were making through my project. Clarifying that, he thought for a bit and suggested I should do a really quick and dirty analysis which tells me something about the big picture question and reply with that analysis instead. He advised me to be firm and assertive in not drawing conclusions about the current experiment (since we only have 2 replicates) but to hint at the progress on the bigger question. Most importantly, he advised and by example demonstrated how to deal with the situation in a calm, logical way.

Looking back at the experience, I learnt 3 valuable lessons which have served me well which I want to share with you:

- Never respond to emotions in a message. Be cool and respond to the facts.

- Look beyond what’s literal to understand the deeper worries of your collaborator. This will help you understand the real reasons behind their worries

- Always keep the big picture problem you are solving in mind. When something fails and you can not resolve the immediate question, use the new information you have to try to answer the larger question.