Is the era of the Position Game coming to an end?

For years it represented the tactical standard, but today perhaps something is changing.

This article was first published by L’Ultimo Uomo. Translation was provided by by kompreno, where L’Ultimo Uomo is included in a curation of the finest analysis, opinion & reporting — from all across the European continent, translated into your language.

The “positional play”; revolution reached its zenith in recent years and, as always in the history of football (although not exclusively in this sport), a counter-revolution has begun that will inevitably lead to a transformation.

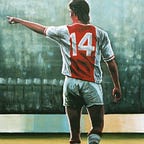

The positional game revolution began 50 years ago in Amsterdam with coach Rinus Michels and player Johan Cruyff, and the technique continued evolving between Milan and Barcelona, with Arrigo Sacchi, Louis van Gaal and Cruyff, this time as coach. It was finally fully developed by Pep Guardiola 15 years ago, again at Barcelona. The positional game of the Catalan coach, who was able to win every time with Messi, Iniesta and Xavi, changed football forever: its principles included the search for positional superiority starting from the back, with at least one free man behind each line of pressure, the search for the third man, the rational and scientific occupation of space with the so-called five channels, and the use

of the half-spaces and of modules such as the 325 or 235 in the offensive phase.

These are principles and codes that we have come to know, appreciate and admire and that, in recent years, many teams around the world (not only the big ones) have adopted. Just to mention the recent World Cup, we can take the examples of Spain and Germany, but also Tite’s Brazil. And, while we are speaking of national teams, we cannot fail to mention Mancini’s national team, winner of the last European Championships. The revolution in positional play has been so great that it has even led to a change in the rules, with the introduction of the possibility of having one or more players inside one’s own penalty area at the goal kick (a rule introduced in 2019 and guaranteeing the team that wants to set up from the bottom a geometric advantage over the attackers). It has influenced even great coaches with different ideas of the game, such as Jurgen Klopp and Antonio Conte, who

over the years have added precisely those principles and solutions typical of positional game to their personal and different playing models.

However, since a couple of seasons ago, defences started to take countermeasures to positional game and a counter-revolution began, following the continuous and eternal tension between offensive solutions and defensive adjustments that the history of every sport has been through. For example, the increase in high, aggressive and often man-to-man pressing is one of the main obstacles to positional game — trying to limit the opponent’s build-up from below and thus the territorial dominance necessary to find the free man, and then occupying the offensive half of the field in order to continue accumulating advantages

by exploiting positional superiority in particular.

The tendency to mark the man and not the space is increasingly common, not only among the teams that adopt a high pressing, but also for those that remain waiting at a lower level and which look for the opponent’s references in midfield with the aim of creating a 3vs3 (obviously in the case of an opponent‘s midfield of three) through many individual

duels. A few weeks ago, Spalletti announced: “In football, there are no longer any patterns. The spaces are no longer between the lines, but between the men, and the skill lies in finding those spaces“. There are fewer and fewer collective defences (lines) to attack, but if there are fewer spaces between the lines, one of the cardinal principles of positional play —

that of exploiting the spaces between and among the lines — is lost.

For years we have asked our Trequartisti to occupy a certain space in positional play and to float in that area, waiting for the ball: “ It is the ball that comes to you and not the other way around. Stand still!“ The advantages that could be gained by "placing" players in the half

spaces were fundamental and almost scientific against certain defences, especially the four- man defensive lines that worked in sections. But these advantageous situations are increasingly diminishing.

“The role: From position to function, from function to relationship“

These inevitable counter-moves by defences are leading to a further evolution of the game. We are arriving (or is it rather a return?) to a game based more on continuous mobility around the ball carrier — a game that is more geared to the exploitation of the players’s characteristics.

In recent years we said that: ”the role is no longer a position but a function, a task“: a builder or an invader; a player who provides width, one who must finish the game in the three- quarter. Now, however, the functions have evolved further, and the “role” has moved from

being a function (more or less specific) to the interpretation of an individual within a “relationship” — it is the continuous and constant movement of the ball, of teammates and opponents that determines the clearances around the player in possession of the ball.

From time to time, the various players in the area of the ball become “vertex”, “lateral”, “support” or “offload”, regardless of their position or initial function. So it is the “relationship” with the ball, with teammates, with opponents — the relationship with the surroundings — that determines and influences the movements, the choices, the game of each player.

This is a further step in the natural evolution of roles, with players once again becoming the centre of everything — no longer caged in a specific position, nor limited by one or more functions. Players will therefore be completely free to express themselves within the confines of common playing principles. There will be fewer star coaches but more star

players. Or — perhaps even better — the coaches will be protagonists in a different way.

This style of play has ancient roots, especially in South America. World champion Argentina won in total opposition to Tite’s Brazil: the verdeoro team, according to South American purists, allowed itself to be too inspired by European “positionalism” by forcing its talented players within the 325 structure, excessively limiting champions like Neymar or Vinicius.

Scaloni’s selection, on the other hand, went back to “la Nuestra”: the very personal Argentine model of play idealised by Menotti in the 1970s. “The centre is the ball. They move according to the ball,” said the World Champion coach recently in Coverciano, on the occasion of the Panchina d’Oro award.

The Argentine team was capable of winning by changing seven different structures (or modules, if you prefer) in the seven matches of the World Cup, trying to adapt to opponents and to Messi, trying — and succeeding — to exalt the Argentine talent by supporting his movements and creating a “supporting cast” of technical and offensive players such as Di

Maria, De Paul, and McAllister, but also Alvarez, Paredes, Lautaro or “Papu” Gomez.

This kind of football is capable of enhancing the qualities, characteristics and emotions of the players, especially the more technical ones, also because connecting the players together makes everyone a little happier. This style of football is not afraid of taking an asymmetrical form and wants to dominate possession not by tactics and predefined spaces

but by technique and dynamic spaces. The focus therefore shifts from space to ball — and to the players. In positional football, the space occupied is fundamental in order to perform better; in relational football, it is individual performance that determines space.

There is a lot of talk in South America right now about Diniz’s Fluminense — about density in the ball area, about asymmetry and rhythms suited to their best players, including Ganso. Asymmetry is an important concept because giving freedom to individuals means that — by being able to move — the team can have numerical superiority in certain areas, leaving

others less covered. This and other aspects are not easy to accept for coaches who are used to total, or almost total, control of their team.

Diniz’s own words come to our aid:

“ My team plays open football, which provides hints and leaves space for you — the player — to create things, to evolve. So over time, if you do things well, you start to recognise what kind of players you have and how you can organise the game to have an advantage over the opponent, how to attack a lot without being vulnerable — this is something I have tried to

improve over time.”

“But it’s an infinite universe: in football we all have to make a lot of efforts in order to know very little in the end. For football is very rich, the field is very big, there are eleven players who can create a lot of interactions against eleven players who create a lot of other interactions. So in football we have to be courageous and give ourselves a little bit of freedom to be able to create things, because nobody knows that much about football. I

think we are always learning, and as I improve, I see an even bigger universe where I can evolve even more. “

In South America, the high point of the game was reached with Brazil in 1982, perhaps the strongest team ever not to have won a title. It was a team with a select quartet of midfielders — Falcao, Socrates, Cerezo and Zico — who were free to find positions on the field, to associate spontaneously, to create fluid structures that were always different from each other, and to manipulate time and space at will.

But we cannot speak of time and space except in relation to something — in this case the players. Let us return to the space between the lines: it is evident that space is not the same if the player between the lines is Messi or someone else. With Messi, even the slightest space becomes lethal, unlike with normal players, which means that space and time are also interrelated to the players, to their movements and interactions.

Therefore, football becomes a game of great mobility, of constant interchange between players, of spontaneous connections that must, however, also include continuous attacks on the line (including off-sides) and in some cases even a point of reference on the opposite side of the ball (which is a legacy of positional play). In this kind of football, superiority will no longer be only positional, but also numerical, qualitative and, above all, affective.

A “non positional”, “functional” and “relational” football

As mentioned before, the “new” functions (totally or almost totally disconnected from the starting role of the players) therefore become those of “support, “offloading” and “vertex” around the ball carrier. Getting the players to internalise all this will not be easy, and will be the new methodological challenge of the next decade; perhaps from rallies we will return to freer possessions in which we should continually recreate the dribble. Certainly the re- attack will be even more important, and so will preventive coverages — this aspect is one of the problems of positional football, with its multiple attackers above the ball line, but it will

be even more difficult to organise with a fluid construction and possession in which the players are constantly changing.

To put it in very basic terms, positions and spaces are the most important element in positional football; they are so important that many call it “positionism”; a footballing technique that Sacchi took to extremes. His teams moved in unison, as if connected by an invisible string, especially in the non-possession phase. Sacchi was the team’s (fantastic) conductor. Now is the time of the jam sessions in which great performers can improvise, if they are connected to each other especially from an emotional point of view. Think of the Messi — D. Alves connection in Barca, or the Totti — Cassano exchanges in Roma — a soulful empathy that turns into art.

Perhaps thinking back to the failures of Riquelme at Barcelona (Van Gaal’s management) or of the aforementioned Ganso in Europe (Sevilla and Amiens) we cannot help but consider the excess of positionalism that there has been in the management of these and other South American talents. Probably Riquelme is one of the players who symbolises non

positional, functional and relational football with his characteristically slow pace, his need to move towards the ball, his many touches to control it, his “pauses” before his inventions, his one-twos.

I spoke about this topic with Francesco Farioli, one of the emerging young coaches closest to the positional game, who has experience as head coach in Turkey; his last term — on the bench of Alanyaspor — ended last February.

“The key concept for me is that of a dynamic balance, like when you ride a bike for example — finding balance through the more or less harmonious movement of what is displayed on the pitch. As you rightly point out, the big challenge will no longer be in analysis, but in methodology, with players less and less tied to the task/role and more and more used to

exploring different areas of the field, and with increasingly varied skills. In past years, we have often heard complaints about ’playing out of position’ or ‘in unfamiliar areas of the field.’ Today, the dynamics of the game, the contrasts, the constant changes of module and the training itself are increasingly guiding/moving the players towards less and less specific,

but definitely broader knowledge.”

Farioli goes on in his reflection:

“Here we cannot but refer to Darwin and his theories on the evolution of species. As thecgreat scientist-philosopher reminds us, the evolution of species occurs as a result of chance and necessity (just like in football). In the struggle for life, the species that is most able to adapt to the circumstances and necessities that arise is the one that survives.“

“Bringing the discourse back to football, consider the evolution of the demands on the footballers and on their physical performance. At some point, there will be no more room for players who are not fast or powerful. And it is precisely in this continuous and incessant flow, between scientific research and scouting, between training methodology and tactical

analysis, between management skills and cultural challenges, that the next great chapter of football evolution will be played out.”

We mentioned several examples overseas, but there were and still are some excellent ones in Europe as well. First of all, Ten Haag’s splendid Ajax, which reached the semi-finals of the Champions League in 2019 after eliminating Real Madrid and Juventus, comes to mind. A team led by youngsters De Jong and De Ligt, and with a density attack consisting of the

three very tight forwards Neres, Tadic and Ziyech.

There is also Spalletti‘s’Napoli of this year, a team that is not very positional but rather very fluid, which manages to fully exploit the characteristics of its players, Lobotka, Kvara and Oshimen above all.

But perhaps the best and most successful European example is that of

Real Madrid, which is coached by Carlo Ancelotti. The Italian coach has built several teams, shaping them based on the qualities of the players at his disposal. The Milan of Pirlo, Seedorf and Rui Costa was a wonderful ancestor of functional and relational football — one of the first teams in modern football to rely on ball control and a true forerunner of Xavi and

Iniesta’s Barcelona in being able to afford so many technical and qualitative midfielders. But also the latest Real Madrid with Kross and Modric in midfield, Valverde as a forwards or mock-outside player (sometimes, however, depending on the need, also a true outside player), Vinicius in one-on-one on the left and Benzema free to partner wherever he sees fit.

We are accustomed to assessing a coach’s skill on the basis of the identity he manages to give his teams, on the realisation of the coach’s model of play almost independently of the players who make them up. This is why some of the best coaches of the last 10–15 years are also very recognisable in their different coaching experiences, even if they have only put

their skills into practice in a few games. On the other hand, the alternative game model we are talking about changes each time, and will therefore be difficult to replicate from team to team, because it is designed around the characteristics of the players. Of course, as with all aspects of football, the context (the league, the opponents) and the level of the players available will be important. With less skilful players, the coach’s work with the codification of movements and/or spaces can bridge important technical differences, but the enhancement of individuality and the possibility of leaving interpretation free also have favourable points.

I talked about this with Davide Ancelotti, son of Carlo and vice-coach of Real Madrid:

“I watch my two sons, who, at the age of four, begin to get passionate about the game of football. Like their dad and any other child, they do it by trying to imitate the exploits of their favourite footballers, shouting their names out loud when they kick the ball or make a save. We fall in love with this game because of the footballers. With this in mind, the real challenge lies in being able to recognise, among the infinite connections that are created between them, those that need to be enhanced (like the one between Messi and Dani Alves, or the famous one between Insigne and Callejon).

“To ensure that through team organisation, a situation occurs in which a particular connection can benefit the collective, to find drills that develop these connections and improve them in training. The positional game in its best versions has been a means of enhancing its performers. Just as for Mourinho in 2010, the low block and counter-attack was the means for Sneijder to launch Pandev, Eto’;o and Milito into the open field. My

opinion on the subject is that — from the beginning — football has always been about the footballers. I don’t think positional game is heading towards its end. Perhaps in some cases, and due to media issues, it has come to be considered a philosophy, an identity necessary to win, more than with other kinds of playing. But I don’t think this is the case. The positional

game is part of that cultural baggage from which a coach can draw to choose which dress to sew on the team. It must therefore be known and studied. When I describe the nature of a coach, I like to use the example of the chameleon, an animal capable of constantly changing colour to escape the dangers that surround it, to adapt to the reality around it. It is not tied

to an identity. Nowadays, there can be two completely different games between the first and second half, just as there can be totally different performances of the same team, depending on the opponent it faces.”

You cannot presume to understand all the variables and predict them. However, this constant change requires a great deal of preparation and study on the part of the staff, who must be able to summarise their work in clear and concise terms and pass it on to the players. It must propose training sessions that are as messy as the game, but have great

organisation at their base. These challenges will probably never be won, but they are what stimulate us and fuel our passion.

For these reasons, the analytical work of the technical staff is also changing. Preparing matches against teams that are more and more fluid and less anchored to structures is increasingly difficult and complicated. The desire to codify situations that are difficult to

codify risks leaving us unprepared for the match. It sounds like a paradox, but it is not. The more I prepare, the less prepared I am.

The emotional factor is crucial in this kind of game. For the players, arriving at the match with too much information (especially regarding defensive opposition) and finding out on the pitch that they are in a different context from the one they have studied can cause an emotional deficit: “What now? What do we do?” A football made of asymmetries, non- structures and more positional exchanges probably responds better to the demands of modern football and to the counter-revolutionary changes we mentioned above. How shall we say it? If you want to mark me man-to-man, I’ll take you around the field and free up other spaces that will be occupied by other players. Positional play has been a great development in the game, but paradoxically its great success is its own limitation: the more teams use it, the more opponents learn to defend themselves against those principles — its positioning tactics and its use of space. The non positional, functional and relational game could be its natural evolution, maintaining many of those principles but giving more freedom to the players, thereby helping to achieve team empathy in such a way that any rotation or position exchange seems natural.

To conclude, it is amusing to think that the parent of the positional game — the Netherlands of 1974 — was probably also the greatest example of fluidity and positional exchanges ever seen at a high level, displaying a social-relational connection that ultimately turned the game into sheer poetry.

Antonio Gagliardi was born in 1983 in Bassano del Grappa. Uefa PRO Coach, tactical and analyst assistant | Former at Italy National A Team and Juventus FC | Coach UEFA Educator FIGC. Winner Uefa Euro2020!