Handling self-citation

‘The distrust of self-citations is completely misplaced’ (Anne-Will Harzing). If relevant, cite yourself, but only up to the norm in your discipline

Academic work is inherently cumulative — and often in tracing the evolution of ideas, methods or evidence an author or research team should cite their own previous work, especially in fields where most work tackles distinctive or applied problems (not widely studied), or follows a particular method not yet widely shared. Yet some commentators suggest that self-citations are problematic or illegitimate and argue that they should not count at all or count less than normal citations. Such critics see self-citation as ‘blowing your own trumpet’. Official bodies often exclude them from cites counts, as if they were somehow corrupt inclusions when measuring academic performance. Some bibliometric scholars concur in excluding self-citations comparative analyses of the research performance of individuals, departments and universities. And indeed there is evidence that self-citations are not as important as citations from other academics in determining how far an academic is an authority within a field . Some producers of bibliometric indicators have also begun to publish the proportion of self-citations, so as to show the number of citations from other authors.

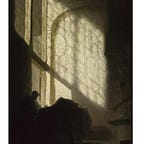

However, there are also good grounds for recognizing that self-citations by individuals and research teams can be a perfectly legitimate and relevant aspect of disciplinary practices in different parts of academia. Figure 4.7 shows large, systematic differences between discipline groups. In engineering sciences two out of five cites are self-cites, ranging down to a fifth for medical and life sciences. In most scientific and STEM disciplines the rate is generally around a third. The social sciences and the humanities generally have low rates with a fifth to a quarter of citations being self-cites, but political science and economics approximate the lowest scores in Figure 1, whereas psychology and education are higher. In the humanities, rates of self-citation are also around a fifth, but language and communication studies use self-citation more frequently.

Figure 1: Self-citation rates across groups of disciplines

Source: Centre for Science and Technology Studies (2007).

Do these patterns reflect solely different disciplinary propensities to blow your own trumpet? It seems very unlikely. Rather this variation seems likely to be shaped by the proportion of applied work undertaken in the discipline, and the serial developmental nature of this work. Many engineering departments specialize in particular sub-fields and grow the knowledge frontier outwards in their chosen areas very intensively, perhaps with relatively few rivals or competitors internationally. Consequently if they are to reference their research appropriately, so that others can check methodologies and follow up effects in replicable ways, engineering authors must include more self-cites, indeed up to twice as many as in some other disciplines. In applied research areas many of these references will also be to reports or other ‘grey literature’, again for wholly legitimate reasons.

Similarly quite a lot of scientific work depends on progress made in the same lab or undertaken by the same author. In these areas normatively excluding self-cites would be severely counter-productive for academic development. And doing so in bibliometrics counts is liable to give a severely misleading impression. In this view the lower levels of self-cites in the humanities and social sciences may simply reflect a lower propensity to publish applied work in scholarly journals, or to undertake serial applied work in the first place.

The low proportion of self-cites in medicine (arguably a mostly applied field) needs a different explanation, however. It may reflect the importance of medical findings being validated across research teams and across countries (key for drug approvals, for instance). It may also be an effect of the extensive accumulation of results produced by very short medical articles (all limited to 3,000 words) and the profession’s insistence on very full referencing of literatures, producing more citations per (short) article than any other discipline.

There are some large gender differences amongst researchers, with men citing their own publications at a far higher rate than do women . Our current state of knowledge does not yet fully control for discipline differences between men and women academic authors, and for men in some fields being more senior on average than women. None the less, it seems that women may be somewhat under-playing links between their current and previous work, perhaps from a misplaced sense of diffidence. Or men may indeed be more boastful or self-referential?

Self-citation also tends to grow with age. Older researchers may do more self-citing, not because they are vainer, but because they are more experienced and can legitimately draw more on their own earlier work than new researchers. In some disciplines too, older academics may do more applied work than younger staff focusing on PhDs or post docs — generating the same reasons to cite their own corpus of work as those found in engineering — namely that their work draws a lot on reports, working papers for external clients, or detailed case studies that may not be easy to publish in journals.

So how should you play self-citations in your own work? It seems prudent for researchers to keep their own self-citation rate slightly below the average for their particular discipline. But it is equally not a good idea to ‘unnaturally’ suppress referencing of your own publications portfolio - because of multiplier effects where citing one’s own earlier work tends to encourage other people to cite it as well. After controlling for different factors, some research found that each additional self-citation increases the number of citations from others by about one citation after one year, and by about three after five years. Other scholars have also found that self-citations can increase the wider visibility of author A’s work. One possible logic here is that reader B doing a literature review sees Author A in her best-known work Z include a citation to some of her lesser known research. If B is conscientious she may follow up and also cite A’s lesser known work, as well as Z. (However, citing less well-known works may not often help A to grow her h score).

For senior academics, citing their own applied research outputs (such as research reports, client reports, news articles, blog posts etc.) makes sense because such outputs are often missed in standard academic databases and sources. Young researchers, with smaller portfolios of publications to draw on, need to handle self-citations carefully. They can be legitimately used to get visibility for supportive works not yet journal-published (such as working papers, research reports, or developed papers under review etc.) or for data sets.

Summing up: 1. Self-cites must only ever be used where they are genuinely useful and fully relevant for the articles in which they are included. 2. Try to ensure that the rate at which you self-cite is somewhat below the norm for your discipline group.

Further resources

How citations work is discussed in more depth in my book with Jane Tinkler, Maximizing the Impacts of Academic Research: How to grow the influence, practical application and public knowledge of science and scholarship (originally Macmillan, 2021, now Bloomsbury Press), Chapter 1.

You may also find useful some of Patrick Dunleavy, ‘Authoring a PhD’ (originally Palgrave, 2003, now Bloomsbury Press) which covers becoming a better author, stylist and self-editor.

And my @Write4Research Twitter feed pulls together a wide range of the latest writing advice.