I have discovered many ways to not make money by writing books

About two years ago, I remember vividly telling a friend of my wife and myself that if there is a gene for being good with money, I did not possess it. I went on to explain that I saw money as an oppressive, sinister force I would never master and that would forever be my enemy. The friend, an accomplished and blunt woman, gave me a look that implicitly asked, “Are you for real, dude?”

She was understandably annoyed that I saw money as some weird, animistic entity that had it out for me as opposed to just, you know, currency. And I think she was annoyed because as a father and husband, I no longer had the luxury to throw up my hands and say, “Oh well, I guess I’m just bad with money and that’s just how it is.”

It’s not exactly cute when a single person is bad with money, but it is forgivable. They’re really only hurting themselves. But when a man with a baby and a wife to support is bad with money, his financial inadequacies hurt his family too, and I think the friend was considering them more than me when I engaged in an unbecoming, if honest act of self-deprecation.

There was undoubtedly something self-pitying about me seeing money as a malevolent force but it came from an honest place. I grew up poor, and like many poor children, I was obsessed with money. As an adult, everything I’ve done to try to make money and free myself from the tyranny of a month-to-month existence backfired.

I grew up reading that the stock market returned something in the area of an annual 9 percent return, on average, so I invested much of my savings in it, and lost, oh I dunno, forty percent of my money before I finally gave up in despair. I bought a home because I thought it would be a good investment and, if I’m lucky enough to sell my home, which is a very big if, I’m still looking at a loss of about fifty or sixty thousand dollars. When I fell into an ocean of credit card debt while researching a book I signed onto a debt consolidation company that I realized too late had absolutely no interest in helping me get out of debt until I paid off their entire exorbitant fees.

So when I say I am bad with money, I have ample evidence to back up my assertion, most recently a thirteen month stint living in my in-laws’ basement after living outside of their basement became prohibitively expensive.

I am not complaining, merely explaining. I’m not complaining because I have been extraordinarily lucky. I started making a living as a writer when I was twenty-one years, old as a staff writer for The A.V Club when the internet was exploding. I was The A.V Club’s third employee and now it is a huge national force. In 2004 and 2005, I was flown to Los Angeles every other weekend to be a panelist on AMC’s Movie Club With John Ridley.

In my early thirties, I got a hundred thousand dollar advance from Scribner to write a memoir about my tragicomic childhood and adolescence in mental hospitals and group homes. When I signed that contract and lived out many writer’s dreams, I thought I’d made it. I thought I had found my happy ending. It turned out I was only just beginning.

I was once again incredibly blessed. The New York Times ran a great front-page review of my 2009 memoir The Big Rewind. The A.V Club ran a huge except online and NPR, one of the few consistent engines to drive book sales, gave it some valuable exposure. Roger Ebert contributed an amazing blurb, as did Patton Oswalt. Yet when I called my exceedingly kind and patient editor and asked how many copies my book had sold, he said a few thousand copies.

He cautioned me that in the grand scheme of things, selling a couple thousand copies of a debut isn’t that bad but I barely heard his words, I was so destroyed. A book I saw as my future now felt to me, in that moment, a tremendous failure. Only a few months into my literary career, I felt it was already over.

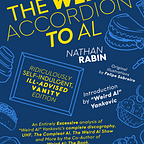

With the benefit of time and hindsight, I now see that as an over-reaction, but it was hard not to see the commercial under-performance of my book as conclusive proof that no one was interested in my story or what I had to say. Yet I still published two more books with Scribner, thanks in no small part to my incredible agent, and another on Abrams Image, a coffee-table book with/about my childhood hero “Weird Al” Yankovic.

I have written so many pieces about how difficult it is to make money as a writer, and particularly as an author, that I could probably assemble them altogether in a poor-selling, unprofitable book. I have discovered many ways not to make money publishing books. This year, for example, I set out to follow up You Don’t Know Me But You Don’t Like Me, a memoir about two intense years following Phish and Insane Clown Posse, with a book about an insane and transcendent and surreal week spent attending both the Republican national convention and The Gathering of the Juggalos with my long-lost brother.

I flew to Cleveland without an assignment, just an intense, burning feeling that this was a once in a lifetime opportunity. I launched a crowd-funding campaign for the first, and perhaps last time in my life, and to my delight, it was extraordinarily successful. I got almost twice my initial goal. I felt like George Bailey at the end of It’s A Wonderful Life. I had put myself out there, made myself vulnerable, and the world was exceedingly kind to me.

I was able to use this money to buy a desperately necessary new laptop and to pay for my family to move out of my in-laws’ basement and into a lovely two-bedroom apartment in Decatur. The piece that came out of my Ohio adventure was too short to be a book so I decided to jump into the scary, exciting world of independent publishing by self-publishing the book (called 7 Days In Ohio) through Amazon’s self-publishing software.

After four books with huge publishers, I was doing everything myself, although Amazon made it all spectacularly easy. I even had a name for my micro-self-publisher: Declan-Haven Books, after my two year old son. Declan-Haven Books was a true family, mom and pop operation, in that I’m its only writer and my wife edited my book.

After seven years of experiencing the cold, harsh realities of the publishing world, I still held out hope that my little book, or book-like-entity, or book-lite, might defy the odds and really connect with an audience beyond the small cult that has made my career possible. It has a lot going for it. It’s about Donald Trump and Insane Clown Posse, two subjects the public has historically found morbidly fascinating. It had a great cover by the distinguished illustrator and artist Danny Hellman. Acting as my own publicist, I scored great, meaty articles about the book in Salon, Utne Reader and Fast Company. Insane Clown Posse tweeted about the book, as did my old collaborator “Weird Al”, who is somewhat popular and well-liked.

Whereas my last book had a much lower Amazon rating than Mein Kampf (seriously) this one is currently averaging more than four stars. It warms the cockles of my heart to know that Amazon users seem to prefer me as an author to Hitler. I’d like to think that’s true in other respects as well.

I vowed not to compulsively check Amazon but of course I did anyway, because I am human, and neurotic, and unlike with my Scribner and Abrams Image books, there was a very direct relationship between books sold and money made. I get a sizable cut out of every book sold, so it in best interest for 7 Days In Ohio to sell as well as possible.

Now there was an article that went viral a while back where a novelist whose first book had gotten rave reviews but, like 90 percent of books on major publishers, lost money. It was an article not unlike this one but it attracted a certain amount of mockery over the writer’s assertion that she would settle for making only 40,000 dollars a year if she could work full-time as a writer.

A good rule of thumb when it comes to expectations is to have a number in your mind that you’d settle for. Good. Now, divide that number by ten. So if the number you’ll settle for as a full-time author is 40,000 dollars a year, you might want to imagine making four grand a year through your literary labors. That’s probably a lot closer to the amount you’ll actually make. For example, I thought it would be great if I could make a couple thousand dollars from 7 Days In Ohio in its first month out, and a couple hundred bucks a month for a little while after that.

I understood all too well why Scribner lost the vast majority of its hundred thousand dollar investment in The Big Rewind. But I figured since my investment in 7 Days In Ohio was the three hundred and fifty dollars I spent on an amazing cover that single-handedly made it look and feel like a real book, my chances of scoring at least a modest profit seemed solid.

Well, I made the mistake of checking to see what my royalties will be and as of today, 7 Days In Ohio has made about 347.22, or a little less than I paid for the cover. It honestly hasn’t sold that badly, it’s just very difficult to make money publishing books, even when you’re only asking for between zero dollars and a dollar ninety-nine, as I am. I even entered the book into a program where readers could read it for free and I’d get a cut for every page read but I have discovered, to my chagrin, that it’s even difficult to get people to read your book for free.

So, yeah, the amount I was willing to “settle for” now seems like an unattainable goal. Instead of a couple thousand dollars and a nice monthly bump, it’s entirely possible my monthly royalties will be a couple of dollars. I have taken control of my career, and discovered firsthand just how difficult it is to be a publisher. I’ve also discovered how difficult it is to make money if you’re only charging ninety nine cents for your product.

Publishing is just a tough business. I’ve been writing pieces for Medium on a pretty regular clip in an attempt to generate interest in 7 Days In Ohio but that does not seem to be a particularly effective tool for selling books. On a recent day I posted two pieces that were collectively read over five thousand times and I sold, I believe, two 7 Days In Ohio and made anywhere between seventy cents and a dollar forty. On a purely practical level, writing Medium pieces in a desperate attempt to make, literally, several dollars selling a few copies of an e-book is about as efficient a way to make money as traversing the streets looking for soda cans to recycle or stealing change from the wishing well in a mall. I would be lying if I said that I wasn’t publishing this essay in part to sell books, but it would not surprise me if this piece is read 100 times and sells zero books. You just kind of throw everything out there and hope that something sticks.

As my own publisher, I suspect I feel like Scribner did back when I was losing them money. I was super proud of the book I’d written. I was super proud of the way the book had been received by readers. I was super proud of press it had received. Hell, I was even proud that the book did okay commercially in a brutal field And while I was disappointed by the sales, and the royalties, I understood that it’s a tough business and you can’t take it personally.

But when you write about the most intimate aspects of your life, it’s hard not to be hurt at least a little bit when your efforts are received the way you way hoped they would be. And its hard not to see disappointing sales as the universe rejecting you and your story. But honestly I am so blessed to even be able to write books at this point. So I am giving myself advice I have given others: write for the sake of writing. Write because you have something to say and a deep need to say it. Write for the love of writing. Write because it’s what god put you on earth to do. Write because you can’t not write. Write because it’s an instinct, as natural as breathing or sleeping. Write because you’re a goddamned writer, regardless of whether or not it’s how you make a living.

Don’t write for the rewards. Don’t write for the money, because it might be something, or it might be 347.22. That said, the money is nice and I still dream of Declan-Haven Books being an actual thing, and not a writerly delusion. One last piece of advice: please buy my book. It’s really good. Or at least read it for free (via Kindle Unlimited). It is definitely worth zero dollars of your money, and a little bit of your time, but then I’m just a little bit biased in that regard.

Nathan Rabin is columnist, dad and author of five books, most recently 7 Days In Ohio: Trump, The Gathering of the Juggalos and the Summer Everything Went Insane