Whose Home Is This? At Least 55,625 Properties Under the Hammer in Real Estate Auctions — and Counting

A data-driven research into housing financialization in Greece and the restructuring of the country by the markets, accompanied by an open dataset.

Illustration & Data Visualization by Olga Souri

The home of a six-member family in Marathonas was to be auctioned off online on September 18 for €68,000. That’s the lowest price any potential bidder had to pay for a 125 square feet house in the northeastern suburbs of Athens. In April 2018, the house was set on fire while the family was trying to warm themselves with a stove. After a couple of days in the hospital, the father of the family succumbed to burn injuries. The auction, which was pursued by Alpha Bank for a business loan that the family had received to sustain their gift shop but could not pay back, was finally suspended due to the very sensitive nature of the issue.

The union of the Greek Communist party tried to stop the auction by blocking the entrance of the notary office. But Greek media presented Development and Investments Minister Adonis Georgiadis as the savior due to his contacts with the Hellenic Bank Association (HBA). The Minister made the following statement regarding the press reports: “Following my intervention to the HBA, the specific auction stopped. We will not allow a tragedy to destroy a family. I thank the HBA for its immediate response and, of course, the bank that suspended the auction.”

It’s been just one of the thousands of houses, stores, factories, offices, parking lots and plots that have gone under the hammer in Greece since May 2016, following the international financial crisis and the inability of households and enterprises to pay off outstanding loans to their creditors. Many see this as a violation of human rights. Big investors and the local elite see it as an opportunity. The result? People who are unable to maintain living standards, displaced by a toxic combination of unemployment, falling wages, rising rents and overtaxation.

It was only on September 19, 2019, that the European Union Commission approved the Greek Primary Residence Protection Scheme to support households at risk of losing their homes. The scheme, which is expected to contribute to the reduction of the burden of non-performing loans (NPLs) in the Greek banking sector, sets strict eligibility criteria in terms of the value of the primary residence and income of the borrower to ensure it is targeted towards those in need. If the borrower stops servicing their loan, however, it is foreseen that the bank can initiate the foreclosure of the property.

On the other side of the fence, the centrally located ‘prime’ and ‘super prime’ areas of Athens have become the destination of choice for international real estate firms and non-European investors, who are attracted by a set of very compelling conditions and circumstances. These include fiscal policies and welfare changes, such as the Golden Visa program; the slowly but steadily rising property prices which exclude small potential players; the social cleansing the government has recently started in Exarchia as part of a development-induced, state-led gentrification plan; and the current boom in tourism and short-term rentals.

Nonetheless, what happens in Athens affects everyone in the country, both indirectly through the extreme concentration of wealth in the capital and directly as the policies transform the whole country. As writer and journalist Anna Minton argues in BIG CAPITAL: Who is London for?, “Today, capital flowing to every aspect of land, property and housing means the whole system has opened itself up to financialization.” Indeed, from unaffordable student housing on Greece’s islands, or complete lack thereof, to prestigious office buildings in the ‘alpha’ parts of Athens, the system is failing to meet the needs not only of those at the bottom but the vast majority of people.

Greece — despite boasting a high rate of homeownership, mostly free of mortgage debt — is a typical example of why this is happening. It demonstrates why the global forces of financialization are entering the national system of housing, which has become about profit rather than people, therefore displacing rather than enriching local communities. But how did we arrive at that point?

Homeownership has a strong tradition in Greece, dating back to the end of the Greek Civil War in 1949. Back then, access to housing was relatively easy, though unregulated. Family savings were invested in a construction sector that was amateur and comprised of small, family-owned building companies. According to British critic, historian and professor of architecture, Kenneth Frampton, essential to this “was the so-called antiparochi, ‘part-exchange’, tradition by which a freehold owner of a typical nineteenth-century Athenian neoclassical house was able, once the house had been demolished, to donate the land in exchange for a certain number of units in a mid-rise apartment block to be built on the same site.”

This ad hoc, self-financing development enabled the lower and middle classes to pay for and build their own homes which secured access to private property for a significant number of Greeks and immigrants, while Athens and the big cities of Greece grew as a patchwork of improvisations and adaptations. A mechanism that, according to researcher Dimitra Siatitsa, “enjoys broad social consensus and tolerance, as individual property and the rights that come with it prevailed over public interest and common/collective benefit […] At the same time, however, it contributed to the anarchic and uncontrolled construction in suburban areas, in forests, and on beaches, creating communities with major problems and great vulnerabilities, as was tragically ascertained in the fire in eastern Attica in July 2018.”

While compensating for the lack of social housing and the economic insecurity faced by many due to unstable post-war socio-economic conditions, antiparochi contributed to the high levels of multiple property ownership and the ability to keep those properties empty without high maintenance and tax costs. Significantly, since the access to off-plan land for low-cost, illegal constructions was relatively easy and an organized state plan rather absent, the culture of investing private savings into one or more houses was considered a form of security, a safe investment strategy, while materializing a social mobility aspiration.

This dynamic changed drastically from the late 1990s and mainly during the 2000s, after Greece joined the Eurozone in 2001, followed by the credit expansion of 2002–2007. Banks started investing less in the so-called ‘real economy’ and increasingly put their money into financial assets. According to Costas Lapavitsas and Jeff Powell, “During the 2000s, lending for finance, real estate and household purposes replaced ‘productive’ lending as the driving force in the loan portfolio of banks.”

Lending from banks, therefore, became the norm — often through aggressive marketing campaigns and with the support of the government — for households to access housing. Saving capabilities became limited and private debt increased massively. The result was a speculative bubble in the real estate sector with two main consequences: the rise in property prices and thousands of empty houses.

According to researcher Elena Patatouka, “The way in which mortgages are distributed in Attica is not merely the aggregate result of household choices but illustrates the banking system’s discrimination policies as regards loan provisions.” In addition to its oligopolistic setup, with the dominance of four large commercial banks based in Athens, the banking sector of Greece became a significant actor in the financialization of housing through the credit scoring of (potential) homeowners. Credit scoring refers to the centralised procedure of rating potential buyers’ creditworthiness in order to approve or reject a loan application after taking into account the candidate’s gender, income, profession, age and nationality as well as the areas where new residences would be purchased. These mechanisms categorise people and areas in groups according to ROI calculations, thus turning them into goods under specific values, available for sale like any other commodity.

Regardless of what forecasts were given by the banks, what happens at the top affects the middle and the bottom, and vice versa, with the flood of capital from the top displacing communities in big cities, while the dominance of a market in short-term rentals drives up property and rent prices for everybody.

The small owners are the small players of the housing market, however, and the effects of the crisis were tragic for most of them. Real estate, a household’s most valuable asset, was targeted by adjustment programmes, while property tax functioned as a tool to increase state income, putting major pressure on property owners. This resulted in the rise of debt to the state and the selling off of property at very low prices in order to maintain living standards. According to the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City, “The current crisis was not a public debt crisis, it became one.”

Households had to cope with cuts in jobs, wages, social benefits and pensions, while the loans previously contracted continued to demand repayments. But repaying them became more and more difficult for most indebted households. In addition, austerity measures augmented this problem of insolvency (the inability to repay a debt) as a significant number of households became reliant on borrowed money to survive and thus became over-indebted. Today, unemployment in Greece still remains, by far, the highest percentage per population in the Eurozone, with youth unemployment above 40%. Additionally, wages in Greece are among the lowest in Europe.

On top of that, the failure of many small enterprises that had taken mortgage loans for their businesses but could not pay them back, resulted in an increase in non-performing loans. Put simply, these are loans that creditors are unable to repay.

The homeownership-driven social inclusion of the previous periods does not exist anymore. The over-indebtedness of households and enterprises had a direct impact on the economic stability of the banking sector and provided justification for the current process of property seizure, through foreclosures and auctions. At the same time, the concentration of ownership by the banks and the entry of investment funds and other non-bank financial actors that purchase bad loan portfolios, including homes, is being allowed to reconfigure the country.

The way properties are acquired and then auctioned by the banks shows how financial narratives, practices and measurements are dominating different branches of government, public authorities and semi-public institutions. This financialization of the state, as human geography professor and researcher Manuel Aalbers has put it, demonstrates how Greece is being restructured by the markets; a restructuring that goes beyond the state’s facilitation of capital circulation and asset privatization. Instead, the evolution of laws has facilitated auctions of private property in order to recapitalize the country’s banking system and get rid of NPLs.

Drafted in 2009, the only response of the Greek state, although contrary to the concept of noninterference with the free market, was the household insolvency (Katseli) law protecting primary residences. The temporary measure included three factors which established the conditions for whether a property could be seized: the income of the family, the amount of debt and the value of the property. Initially, the law protected around 90% of homeowners. However, it didn’t manage to deter procedural abuse by the so-called ‘strategic defaulters’ — those who take advantage of the protection framework when they can actually pay — even though this group of borrowers constitute a small percentage according to bank data. As a result, since 2014, the supposedly horizontal protection measures have been repealed and the ban on foreclosures has been abolished by the facilitation of auctions and the institution of the electronic auction platform eauction.gr by the Notary Association of Athens, Piraeus, Aegean and Dodecanese.

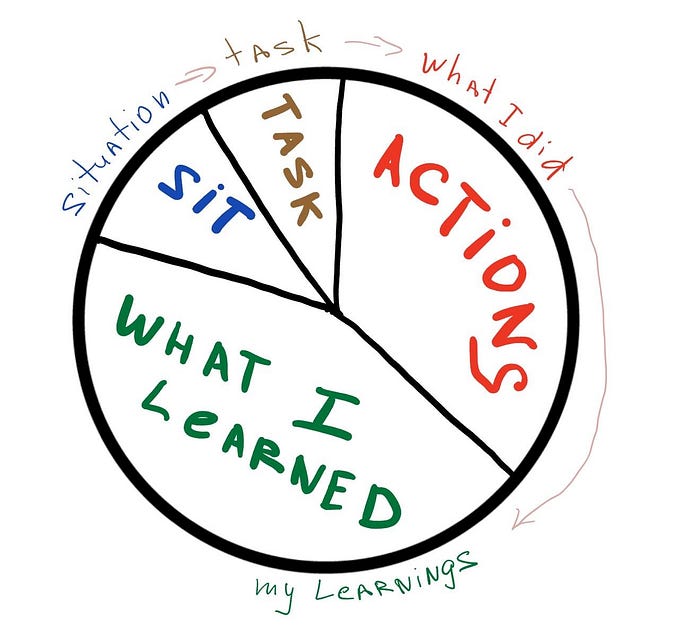

To better understand how this platform accelerates the processing of auctions, we wanted to look in some detail at every property that has appeared online. However, unsurprisingly, no data is available online; nothing from the Notary Association website; nothing from Athens Bar Association website. The only way to collect this data was to loop through every property on eauction.gr to collect the relevant information and put it into a dataset of 45,918 lots that can then be analysed. Challenging, but totally worthwhile.

The dataset, which comes along with 22,119 items of documentation for each unique online auction in PDF and Word Doc format, in Greek language, gives open access to basic information on the identity of the debtor, including their name and VAT number, and the hastener pursuing the auction, the starting bid, the current status and date of the auction. New properties are being added on the platform on a daily basis. All cases can be tracked and counted so that journalists, activists, academics, advocates and active citizens can oversee what is going on in the platform while generating new knowledge and empowering affected communities.

Access the dataset in CSV format here and the documentation database here.

The data covers the whole country and the study period is from November 18, 2017, when the first property appeared on the platform, until September 1, 2019. With this data, it is possible to isolate every property which was listed on the platform at any point in this period. Where are those 45,918 properties located and how much do they cost? How many of the auctions were actually conducted? Taking the assumption that social and economic pressures can target certain vulnerable groups, with this kind of data, we would be able to prove (or disprove) this. But before proceeding, let’s see why the online platform was developed in the first place.

According to the 2019 European Commission Report for Greece, it was first put into use as “an alternative for and [to] eventually replace the highly problematic and contested conduct of physical auctions. It has allowed for the resuming of liquidations of collateral, after a long moratorium followed by a de facto blockage of physical auctions by activists throughout Greece.”

As architect and activist Tonia Katerini narrates, the risk of people losing their home triggered the growth of a large anti-auction movement, connected to the pressing targets of reducing the share of bad loans in bank portfolios. “From the beginning, our main purpose was to challenge and reverse the dominant idea that those suffering a heavy debt burden were personally responsible for their perilous situation and that consequently there was no need for a law protecting private property […] At the same time, we contacted all of the other opposition groups in Athens. This included collectives such as neighbourhood assemblies and solidarity initiatives which had proliferated after the crisis. The intention was to create an alliance with a broad enough scope capable of challenging property seizures.”

What we found on eauctions.gr

Undoubtedly, the online auction platform has dramatically expedited the rate of auctions. Essentially, though, it has de-linked real estate and place by making the intrinsically local and fixed nature of real estate into something liquid and therefore tradable on global financial marketplaces. “By using the online auction service, you can participate in online auctions without your physical presence using a computer.” That’s the first thing you read when you enter the platform.

The indebted borrowers include both individuals and businesses. Among the individual debtors several have multiple properties against their names. On August 31, at least 30,134 individuals had more than one property listed. Some of the individuals clearly held large property portfolios. In one instance, a single person is named against 87 lots. Therefore, there are 22,119 items of documentation in our database instead of 45,918 — which is the exact number of electronic auctions within our study period. Because, for such properties, we have downloaded just the primary piece of documentation, including details for the whole list of relative auctions.

In terms of prices, there is great disparity in the starting bids for individual lots, with €52,000 being the median. At the top of the scale are the production facility of the solar power generation company HelioSphera in Tripoli, Arcadia (€37,449,000); the facilities of IRIS printing company in Koropi, Attica, one of the largest in Southeast Europe (€35,183,140). Also at the top is ‘the most expensive house in Athens,’ a six-storey luxury residential tower minutes away from Syntagma Square (€35,000,000), whose owner, arms dealer Konstantinos Dafermos, was arrested in 2015 for illegal payments given to secure a contract to supply Kornet anti-tank missile launchers to the Greek armed forces. Also listed: 6 million shares registered to Global Equity Investments SA which is based in Bridel, Luxembourg (€33,300,000); Erasinio Hospital in the Vari area of Attica, the first private oncological hospital in Greece and one of the largest investments made in the health sector in the country, which never actually started operating (€31,942,159.30); Folli Follie’s 35.7% stake in Attica Department Stores (€29,456,111.88); and the primary facility of Hydra Beach resort, located in southeast Greece across from the eponymous isle of Hydra (€27,807,000). At the bottom of the price range are storage rooms for €900, cars for €300, individual parking spaces, even coffee tables.

What we did not find (and why this information is important)

We managed to map 26,976 properties by regional unit. This number, however, represents 58.7% of all the properties in question as real estate type and location information are not available for auctions with posting date before September 24, 2018. This kind of information, simply put the exact address of the real estate, is only available in the documentation of each auction in our database. Mapping every single auctioned property would allow us to find hotspots of gentrification, eviction, and displacement. See how Princeton University’s Eviction Lab has used mapping to advocate for change.

Since information on the real estate type and total debt of their owners is limited, a point of concern is the calculation of the exact number of primary residences auctioned and the smaller debtors. When the previous government has spoken about protecting small homeowners, they draw the line at homes worth up to €300,000. If thousands of families are being evicted from their homes, maybe we can and should do something about that? See how OpenUp and their network are trying to gather information by digitising court records, gathering data at court, and scouring databases online and offline to piece together a useful picture of the state of eviction in South Africa.

When it comes to bidders, we don’t really know who bought what and for how much. That’s how financialization works; it serves to allow anonymity for the rich. On the other hand, land — and the devastation caused to the lives of individuals and communities who have lost it — is personal and the resulting wave of displacement can lead to an increase in mental health problems.

According to the European Commission, however, “Four out of five successful auctions conducted since the platform was activated led to the purchase of the collateral by the bank.” The banks are determined, if necessary, to buy the majority of properties sold at auction. Apart from reducing the volume of NPLs on their balance sheets, this strategy will prevent a price collapse in the property market, while forcing strategic defaulters to come forward to settle their debts.

Once again, banks will play a significant role in the financialization of real estate as the commercially attractive properties in their portfolios will be saleable at the first sign of an uptick in the market, turning the country into a playground for the rich. But we have to act. If we want housing to be a public good and not a vehicle for investment, we need more democratic control, not less. We must increase the visibility of the problem and advocate for those who are at risk of losing their homes, knowing that the struggle against the seizure of private property is a struggle for human rights.

Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter and Instagram, and subscribe to our YouTube channel.

If you have any corrections, ideas, or even profanities to share, feel free to email us info@athenslive.gr