Cultural Insurgents, Part 1

The many forms of neocon comic books.

Where are the great conservative comics and graphic novels of the 20th and 21st centuries? A few people want to know.

Amity Shlaes is the author of National Review essays like “Repeal the Minimum Wage” (from a “humanitarian” angle) and a revisionist history of the Great Depression, which is now a graphic novel illustrated by Paul Rivoche. In “A Cartoon Manifesto,” published this May, Shlaes reveals that comics are “exploding” in schoolrooms and libraries these days, but just like another big bang that I could point to, conservatives have been wholeheartedly denying its existence.

Shlaes lists three reasons why conservatives aren’t capitalizing on this new frontier:

- “the political bent of the artists themselves” → they’re liberals

- “conservatives themselves have expressed no demand for graphic novels” → but readers in general are practically extinct anyways

- “intellectual hesitation”

She ends her manifesto by focusing on this third reason:

By turning their collective nose up at graphic books, conservatives surrender education ground to the more artful progressives. In the case of economics, conservatives leave fans of markets, not to mention fans of balanced history, unequipped to rebut when the progressive cartoon books come along.

Shlaes hasn’t exactly turned her nose down to graphic novels either; she repeatedly calls them “cartoon books.” Liking Maus and Persepolis, which she admits, is probably the bare minimum of a commitment to the form. Her adoption of comics reads as little more than opportunistic: there’s money to be made (despite the demand problem), and hopefully comics can be used to stamp out Marxism, which has a “troubling” monopoly on content.

Content is the keyword here, since “form” rudimentarily means “as a cartoon.” If Shlaes’ adaptation is any indication, according to Jeff Shesol’s review, its thoughtless formal construction quite aptly reflects the foolishness of the original book:

Rivoche’s cartoons only underscore the cartoonishness of the 2007 edition: black-hatted government inspectors bang (“BAM! BAM! BAM!”) on the doors of small-business owners, jabbing fingers and barking orders (“I am the code authority and what I say goes”).

Keep using “cartoon books” and what you get is “cartoonishness.”

The conservative comics gap, however, is deeper than this list of three concerns. In an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal, Chuck Dixon (famous Batman writer) and Paul Rivoche (Shlaes’ artist) build on the National Review manifesto by diagnosing “the political-correctness problem” in modern comic books that has muted the conservative voice:

Batman became dark and ambiguous, a kind of brooding monster. Superman became less patriotic, culminating in his decision to renounce his citizenship so he wouldn’t be seen as an extension of U.S. foreign policy. A new code, less explicit but far stronger, replaced the old: a code of political correctness and moral ambiguity. If you disagreed with mostly left-leaning editors, you stayed silent.

This is a defense of the Comics Code of 1954, which sought to save children from the glorification of violence and perversion of sexuality in the unfettered 1940s. Henceforth, comics would need to be stark: good guys are patriots, while bad guys are drug users who go by the name Bane (Dixon’s creation). Despite this dividing line between the unequivocal then and equivocal now, Dixon and Rivoche also summon up a pre-political world, where the comics community was once an efficient open-concept office, a Pequod of competing viewpoints and common purpose:

Nobody cared what an artist’s politics were if you could draw or write and hand work in on schedule. Comics were a brotherhood beyond politics.

When Dixon and Rivoche celebrate the honest, hardworking male utopia of midcentury comics (a kind of reverse Paradise Island), they obscure the exploitative labor conditions under which most writers and artists worked for “half a century,” as Jean-Paul Gabilliet notes in Of Comics and Men (120): “the logic of individual creation” was alien to the assembly line production of comics until the 1980s, and creators were systematically denied earnings and credit for their creations (122).

Tellingly, Dixon began his career after 1981, when the mainstream companies began reckoning with creator ownership, so Dixon’s “brotherhood beyond politics” misses the proper decade. Comic books in the 80s and 90s were profitable vehicles of individual expression, and Dixon’s white/black worldview was, in fact, a branded commodity with a personality attached.

Dixon and Rivoche end their own manifesto with yet another fantasy of the past:

We hope conservatives, free-marketeers and, yes, free-speech liberals will join us. It’s time to take back comics.

Because you had them in the first place? A better case is to be made that the first comic strips of the early 20th century “were proletarian in a contained, inclusive way,” as David Hajdu puts it (11). That word, “proletarian,” reeks of Shlaes’ foe, Marxism, and Hajdu’s description of the very urban, multicultural ethos of early comics—“intimate, knowing, affectionate, and merciless” (11)—continues to inform thoughtful comic making in the 21st century (Love & Rockets, for instance).

The dreaded “moral ambiguity” of contemporary comics is better seen as “complexity.” It traces back to the false resolutions at the end of R. F. Outcault’s Buster Brown strips in the 1900s, which mock the pieties of parenting and champion the smiling insurgency of the child. This is also the very tension between word and image, law versus lawlessness, at the heart of comics, which the illustrated slogans and simplifications of Shlaes’ Forgotten Man do not understand. Jeff Shesol’s review sums it up:

In the modern conservative movement you have, by contrast, a denial of complexity and an abhorrence of nuance; you have what the historian Richard Hofstadter, half a century ago in his “Anti-Intellectualism in American Life,” called “the one-hundred per cent mentality”—a mindset that “tolerate[s] no ambiguities, no equivocations, no reservations, and no criticism.” This makes for pretty good propaganda, but lousy literature.

To be continued.

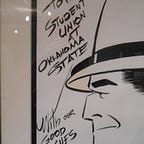

Part 2 will look at what Michael Kimmage calls “the plight of conservative literature” with an example of conservative content from Oklahoma.