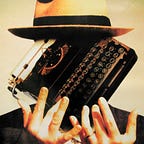

In Defence of The Darjeeling Limited

Wes Anderson’s ill-fated Indian undertaking

In February 2018 the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made a hapless diplomatic visit to India. Wearing immaculately curated primary-coloured traditional garb he posed for carefully composed shots in front of the Taj Mahal and the Harmandir Sahib. India’s junior agriculture minister did the official receiving, in the absence of anyone higher-level. At one point, Trudeau accidentally spent an evening with a Sikh extremist. Both in terms of the odyssey’s visuals and its narrative, Trudeau appeared to be blundering through his own personal Wes Anderson movie.

But Wes Anderson’s India movie already exists.

The Darjeeling Limited arrived in 2007: the follow-up to Anderson’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004), nine years on from his revered breakout Rushmore. Predictably, it was not much admired by Anderson’s detractors, who bemoaned its archness, its fussiness, its artificiality and its whiteness: the same criticisms all his movies get, with bonus accusations of poverty tourism and cultural appropriation. But Anderson’s usual admirers widely saw it as a stumble too, and its reputation, unlike The Life Aquatic’s, hasn’t improved in the decade since. Features ranking Anderson’s filmography to date at IndieWire, Time Out and Nerdist all place it second-to-last, above only Bottle Rocket (1996, which they excuse as juvenilia from a not yet fully formed auteur). Rolling Stone’s Bilge Ebiri ranks it last, several places beneath an American Express commercial, as “the one outright disaster in Anderson’s body of work.”

It’s better than that.

The Darjeeling Limited is the story of the estranged Whitman brothers: Francis (Owen Wilson), Peter (Adrien Brody) and Jack (Jason Schwartzman). Their father died a year ago, and they’re now undertaking a journey across India by train as a bonding exercise. Francis is the instigator, swathed in bandages having recently survived a motorcycle accident. Peter is freaking out about his own imminent fatherhood. Jack is recovering from a break-up with an unnamed girlfriend (played by Natalie Portman in the film’s accompanying short Hotel Chevalier). Francis’ ulterior motive for the journey is eventually revealed to be a reunion with the Whitmans’ mother (Anjelica Huston), who is a nun at a Himalayan convent. This does not sit well with Peter and Jack. The meticulous order of Francis’ planning — he even employs an assistant, Brendan (Wallace Wolodarsky), who prints and laminates a daily itinerary on board the train — begins to untidily unravel. Shenanigans ensue.

Even though it’s still clearly Anderson-authored, the circumstances of filming with a real moving train in real locations mean it doesn’t, for once, feel designed and choreographed to within an inch of its life. This is Anderson’s loosest film, and if his work can sometimes feel chilly, in Rajasthan Darjeeling swelters. That combined with — unusually for Anderson — a screenplay co-authored with Schwartzman and Roman Coppola, gives the film a distinctly separate vibe to the rest of his canon. It feels as if the other two writers are undercutting Anderson’s fastidiousness, as Peter and Jack do to Francis. Darjeeling feels like well-aware self-satire, rather than unwitting self-parody: Anderson allowing his friends and collaborators to gently mock him. The none-more-Anderson Hotel Chevalier companion piece compounds that idea: a static, formal vignette about Jack’s over-planned, over-designed final romantic liaison; the dialogue so clipped and blank and stylised it wouldn’t be out of place in a Yorgos Lanthimos script.

Inside the carriages it’s a typically Andersonian doll’s house. The costumes — including the brothers’ splendid matching pastel pyjamas — are by Milena Canonero, who did Sophia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuiton designed the Whitmans’ opulent luggage: a none-too-subtle metaphor for their emotional baggage. But this film and its characters continually resist that perfection and order, and the brothers are eventually thrown off the train altogether. So we get the typical Anderson confined space but also a palpable sense of somewhere real outside it. Cinematographer Robert Yeoman makes this the first Anderson film to look really beautiful in a way that isn’t entirely artificial.

Some commentators have found the Whitmans to be Anderson’s least likeable set of characters, but the fact that they’re idiots is entirely the point. They’re the Three Stooges, far out of their natural element, trying to force a spiritual epiphany. Or one of them is. The other two don’t really care at all. That fecklessness undercuts criticisms of this being a sort of fantasy India like Jeunet’s Montmartre in Amelie. Anderson is avowedly channelling Jean Renoir’s The River, along with the work of James Ivory and Satyajit Ray, but India is presented as the brothers have been conditioned to see it. “This is a movie from the point of view of three American tourists,” Anderson explained to The Guardian’s Xan Brooks. “Their window is always going to be pretty narrow.” The Whitmans’ gormless experience is the “real” India resisting them (although they get their epiphanies anyway, if not the ones they were expecting: the film sort of has it both ways).

Away from the train, the brothers encounter a tragedy in an Indian village. Often criticised as jarring or queasily patronising (or both), you can equally argue that it’s at least an attempt at a moment of genuine emotion in contrast to Anderson’s usual artifice, with a committed and sincere performance from the late, great Irrfan Khan. It also anticipates the laudably downbeat surprise lurking at the end of Anderson’s much more austere The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014).

And of course, there’s the music: Anderson indulging once again his enormous proclivity and facility for picking impeccable drops for a jukebox soundtrack. There are numerous perfect cues from Ivory and Ray films; a blast of the Rolling Stones; the British Peter Sarstedt providing French ennui at Hotel Chevalier; the French Joe Dassin singing about the Champs-Élysées over end-credits footage of rolling Indian rails. The Darjeeling Limited is an “exotic” departure, but in the end, it’s uniquely Anderson after all. “With my style,” he told The New Yorker, pondering Darjeeling’s perceived failure compared to Slumdog Millionaire’s success, “I can take a subject that you’d think would be commercial and turn it into something that not a lot of people want to see.”

Those people, to this day, are missing out.

This feature was originally published at the late lamented BirthMoviesDeath.