The Running Man (1987): Running On Empty

In 2011 we got a new Conan the Barbarian. In 2012 we got a new Total Recall. In the last few years we’ve had a new It and a new Pet Sematary. But if there’s one Arnold Schwarzenegger movie or one Stephen King adaptation that’s really worth doing over, it’s The Running Man.

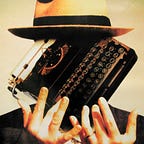

King wrote The Running Man in 1982 under his short-lived “Richard Bachman” thriller-author pseudonym. In the story the year is 2025, an age when the populace is glued to gameshows like Treadmill to Bucks, Run For Your Guns, How Hot Can You Take It and Swim the Crocodiles. All exploit the sick and the needy for the entertainment of the docile but bloodthirsty “Free-Vee” audience. Ben Richards joins a line of equally desperate wannabe contestants that stretches back from studio The Games Building for nine blocks.

The Richards of King’s version is 28, 6’2 and a malnourished 165lb — very much not Arnold. He’s recently been laid off from his blue-collar job at General Atomics, leaving him with scant resources to pay for medicine for his dangerously sick 18-month-old daughter. His wife has been turning tricks for extra cash. Richards is regarded as “antiauthoritarian and antisocial”. In the past he’s been expelled from school for kicking the assistant principal in the ass, and in trouble for calling a union superior a “cornholing son of a bitch”. He has a definite Eastwood vibe, although heyday Eastwood was a decade older. The Running Man’s producer Dan Killian, meanwhile, you could imagine being played by Yaphet Kotto. Kotto is in the movie, but not in that role.

The Running Man itself is the most popular show of all. Contestants are given a head start and some stake money to get as far away from the Games Building as possible before the professional “Hunters” begin their pursuit. The hunted earn $100 for every hour they remain at large, and a bonus $100 for every Hunter they kill. If they survive a month on the run, they win a grand prize of a billion dollars — and get to live. Every other potential scenario ends with their demise, which the audience hopes is as grisly as possible. “People won’t be rooting for you to get away,” Killian tells Richards. “They want to see you wiped out and they’ll help if they can.” Viewers are rewarded for providing the Hunters with sightings, and punished for harbouring fugitives. The novel’s action races through New York, Boston, New Hampshire and (of course) Maine, until a devastating climax that, post-9/11, is probably now unfilmable.

There’s obviously a strong thread of jet-black satire at work here, and King said in his introduction to the compiled Bachman Books that the novel “moves with the goofy speed of a silent movie.” But it’s also bitterly angry, finding time to rage about poverty, monolithic corporations and environmental issues along its breakneck route. King wrote it in a furious 72-hour marathon and, barring minor tweaks, the book that was published was essentially that single draft. “I had an energy I can only dream about these days,” says the man who’s published ten books since 2014.

The movie version came along in 1987 as the Arnold vehicle in between Predator and Red Heat. Steven E. de Souza (Commando, Die Hard) wrote the screenplay, which went through various drafts for various directors including George Pan Cosmatos (Cobra) and Andrew Davis (Above the Law, Under Siege). Paul Michael Glaser recalls originally turning it down when he learned there would be barely any prep time. Davis got the gig, but was fired when, after two weeks filming, the production was already a week behind schedule. Glaser took it on after all. He’d almost walked away from Starsky & Hutch a decade earlier because he thought it was too violent and stupid. Now he was directing a film in which Arnold garrottes a man with barbed wire and says, “He was a real pain in the neck”.

De Souza makes the year 2017, when a nebulous totalitarian government is in place and Mick Fleetwood and Dweezil Zappa lead a resistance movement. Arnold’s Ben Richards is a helicopter lawman who refuses to fire on an unarmed protest over food shortages and is sent to a sweaty industrial detention foundry where he has a beard and glistens and carries girders around. He breaks out of there and finds the rebellion, but is then captured again, framed as a mass-murderer and, thanks to Killian’s intervention, sentenced to The Running Man (with a “court appointed theatrical agent”). Killian here seems to be all things to The Running Man: its presenter as well as its producer. He’s played with impressive, self-aware relish by Richard Dawson, who’d hosted Family Feud for years and had a reputation for smarm. His Running Man studio show has a more explicit Price Is Right aspect (“Come on down!”) than King’s, with audience members winning prizes as Richards progresses elsewhere.

In this version, the runners are dropped into a cordoned off area of slum Los Angeles and have three hours to make it through four game zones, only one of which is in any way differentiated from the characterless others (an ice hockey rink, in the only sequence Davis completed). In the book, the multiple Hunters are anonymous, shadowy figures until the final-stretch entrance of the hardcore McCone. In the film, the “Stalkers” ultimately number only four, and each has a gimmick: Professor Sub Zero (hockey, exploding pucks); Buzzsaw (chainsaws, “He had to split”); Dynamo (electricity and, er, opera); Fireball (flamethrower and jet pack, “What a hot head”). Jesse Ventura’s Captain Freedom, disappointingly, stays on the reserve bench in a turtleneck.

King thinks his novel is goofy, but it’s Dostoevsky compared to a fatally rushed and compromised film where it looks like nobody other than Dawson could quite be bothered anymore. Its production values are abysmal, its photography flat, its tension non-existent. Everyone appears merely to be going through the motions in the knowledge that what they’re working on is unlikely to turn out well. Ironically the film ultimately has the same contempt for its audience as the society it’s satirising. Maybe that contempt was justified: The Running Man opened at number one and turned a profit.

Occasionally commentators like to pick up on the prescience of both film and novel — their apparent anticipation of reality TV and “fake news” (although neither predicts digital media or the mobile phone). But there’s so much more to run with here; so much potential to drop The Running Man into the current climate of alarmist social media and deep fakes and mass surveillance and “fine people on both sides”. And all within the context of an action narrative that plays out like The Most Dangerous Game (or Hard Target) on a nationwide scale, with some of the headlong momentum and paranoid, panicked pursuit of Spielberg’s Duel.

But until that happens, there’s always Hunted, the UK show based on an extremely similar premise to King’s novel (but partially faked and without the death). Contestants can run anywhere in mainland Great Britain, pursued by Hunters who have law enforcement and intelligence experience and access to CCTV. Viewers can — and do — turn in the runners for rewards. And if the runners manage to stay at large for 28 days, they win £100,000. The show began on Channel 4 in 2015 and has so far run for six seasons (including a celebrity version for charity). It was adapted for the US on CBS for a single seven-episode season in 2017, with the grand prize set at quarter of a million dollars. Weirdly, the US version had a contestant called Stephen King. He won.

This feature was originally published at the late lamented BirthMoviesDeath. In the time since, Edgar Wright’s name has been attached to a new Running Man movie…

Stephen King’s novel is published in the UK by Hodder and in North America by Pocket Books, both as a single volume and part of the Bachman Books omnibus. The 1987 film is widely available on disc and digitally.