A Poet, “In Paris,” and a Period

Poet Carl Dennis settles a debate

In Woody Allen’s classic movie “Annie Hall,” he’s waiting in line outside a movie theatre and a pompous guy behind him is pontificating to his wife — pompsplaining — about Marshall McLuhan, the prophetic philosopher and educator on culture and technology. Allen gets into a heated argument with the guy, basically saying it’s ok to be totally wrong about McLuhan but just not so loud about it.

The guy self-importantly announces something like, “well I happen to be a professor at Columbia University and I teach a course on culture and media and I know my McLuhan.” To which Woody says, “oh really, well I happen to have Marshall McLuhan right here,” and he pulls the actual living Marshall McLuhan from behind a screen who proceeds to tell the professor, “I heard what you were saying, and you know nothing of my work. How you ever got to teach a course in anything is totally amazing to me.”

Is there any better way to win an argument? “Well, I’ve got Socrates right here and…”

As Woody Allen said, though, “wouldn’t it be great if real life were like this?” Which, of course, it isn’t. In real life, deliverance in an argument is many degrees of separation away.

Except in real life I had this experience (kinda) with a Pulitzer Prize winning poet. It turns out that only two degrees of separation is enough to get a real, live, acclaimed poet to personally settle a question about a poem.

But this was not a movie. In real life, nothing was delivered. I lost the debate.

How it happened

I organize several poetry reading groups for people who are poetry-curious or poetry-reluctant. I’m no professor, no academic, I’m just an enthusiast who has discovered that it’s not hard to get even poetry-averse people enthused by and often in love with a poem, if the poem is any good.

For one group, I recently gathered a selection of poems about Paris, and one was by a poet whose name and work I was unfamiliar with. I had been hunting specifically for Paris poems so I’m sure I found this one by its title: “In Paris.” I was unfamiliar with the poet but instantly captured by the poem.

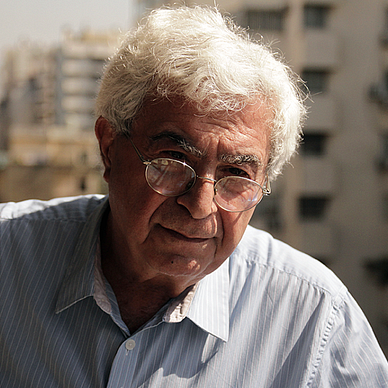

The poet is Carl Dennis. I figured I’d look him up to have something to say to the group. To my private (and now public) embarrassment and chagrin, Dennis was unknown to me but was hardly unknown outside my own little orbit. In 2002, he won a Pulitzer Prize in poetry, eclipsing the other two nominees, both of whom were future Pulitzer winners. His poetry has been published in many important magazines and poetry journals, including some I have occasion to read.

I also learned that Dennis taught for years in the English Department at the State University of New York at Buffalo, where the faculty included renowned poets whose names I did know and have even read, like Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, Susan Howe, Anselm Hollo, and Charles Bernstein. (Disclosure: I’m no fan of the “schools” of poetry these poets were part of and I don’t read much of their stuff.)

To make matters even worse for me, I went to SUNY/Buffalo. And I was an English major. And I was learning there (allegedly) while Carl Dennis was teaching there. We were one degree of separation away as I walked past his classroom.

Maybe he only taught graduate students. Or may it was the early 1970’s and I was a long-haired kid from Brooklyn whose main influence was Groucho Marx and Jefferson Airplane. And Dennis really was an unknown poet back then. So our one-degree gap was all it took to keep me in the dark.

But for present purposes, I now had my intro about Dennis for the poetry group. Everyone had a good laugh when I gave this background about my unknown poet, after which I read his poem aloud.

And for a long while no one spoke. You could hear the silent re-reading, the thinking, the unsaid questioning. We were all engaged, provoked by a poem, and, since the poem was about Paris, maybe a little in love. Here’s the poem.

In Paris

Today as we walk in Paris I promise to focus

More on the sights before us than on the woman

We noticed yesterday in the photograph at the print shop,

The slender brunette who looked like you

As she posed with a violin case by a horse-drawn omnibus

Near the Luxembourg Gardens. Today I won’t linger long

On the obvious point that her name is as lost to history

As the name of the graveyard where her bones

Have been crumbling to dust for over a century.

The streets we’re to wander will shine more brightly

Now that it’s clear the day of her death

Is of little importance compared to the moment

Caught in the photograph as she makes her way

Through afternoon light like this toward the Seine.

The cold rain that fell this morning has given way to sunshine.

The gleaming puddles reflect our mood

Just as they reflected hers as she stepped around them

Smiling to herself, happy that her audition

An hour before went well. After practicing scales

For years in a village whose name isn’t recorded,

She can study in Paris with one of the masters.

No way of telling now how close her life

Came to the life she hoped for as she rambled,

On the day of the photograph, along the quay.

But why do I need to know when she herself,

If offered a chance to peruse the book of the future,

Might shake her head no and turn away?

She wants to focus on her afternoon, now almost gone,

As we want to focus on ours as we stand

Here on the bridge she stood on to watch

The steamers push up against the current or ease down.

This flickering light on the water as boats pass by

Is the flow that many painters have tried to capture

Without holding too still. By the time these boats arrive

Far off in the provinces and give up their cargoes,

Who knows where the flow may have carried us?

But to think now of our leaving is to wrong the moment.

We have to be wholly here as she was

If we want the city that welcomed her

To welcome us as students trained in her school

To enjoy the music as much as she did

When she didn’t grieve that she couldn’t stay

Sois ici maintenant (Be here now)

Time steals us all away and leaves photos as proof of existence.

This narrative poem — a dramatic monologue — is teeming with imagery, feeling, and thought. Time, the ephemerality of the moment, Paris, romance, obsession, the flowing Seine, sepia-toned photographs, photography’s power and powerlessness: the group discussed all these things, and more I’m sure.

The speaker is in Paris with his — wife? paramour? friend? — and he knows she is frustrated with him. He’s obsessed with a 19th century photograph they saw in a print shop of a Parisian street scene with a woman carrying a violin case. He can’t stop thinking of the woman, long gone from Paris, faraway from now, and lost to history.

We all could relate to both sides of the poem’s modern-day scenario. On one side of the couple’s dilemma is the seductive power that a photograph has over the narrator (and, by proxy, over us readers). The other side of the dilemma is the “here and now” that the narrator’s companion wants to enjoy while strolling with her man.

Reflecting the narrator’s obsession, the present-day “she” in the poem is barely there. We know much more about the long-gone woman in the photograph. “Enough already,” we imagine the living woman wants to say, but she doesn’t have a voice in the poem. The narrator simply tells us, “She wants to focus on her afternoon, now almost gone.”

But wait! The woman who “wants to focus on her afternoon” is the woman in the old photograph, not the woman in the present. This man cannot stop thinking of that ghost in the image. “Paris is laid out in splendor before you now!” I want to shout at him. “Pay attention to the angel in front of you!” But I cannot reach the inattentive narrator who is just a disembodied “voice” in a poem, just as he cannot reach the woman in a faded image from the 19th century.

Look how he can’t stop himself! He promised — promised! — in the poem’s first line to “focus on the sights before us” rather than on the beguiling antique photograph. “Focus” is what he says — just like a camera does. Perhaps “focus” is not the reassuring word the narrator should have chosen, but it’s honest because his focus keeps returning to the camera’s subject a century earlier. He says he won’t “linger long” on her death, as he clearly already has and proceeds to do some more.

About halfway through the poem, the sun comes out and it seems like our haunted hero is going to come back to the present. He sees how “the gleaming puddles reflect our mood,” and he all but says “honey! I’m home!” But, no, he falls instead through the camera’s time portal back to the muddy puddles that his 19th century inamorata is stepping around as she smiles to herself. At this point in his preoccupation, the narrator exceeds the four corners of the photograph and simply creates unknowable facts about her successful audition and her musical studies.

Just as things are getting a little out of hand, the narrator — and the poem — asks an important question: why does he care what became of his enchantress if she herself, living wholly, didn’t care to “peruse the book of the future”?

Why does he care? What ensnares him? Photography gives us the illusion that we can stop time right — snap! — now. Old photographs let us imagine more fully this vanished place in that vanished time, like the prototypical 1838 photograph of a Paris street, above. They let us meet and look into the eyes of the dead. Haven’t you looked at a photo from, say, Coney Island in the 1920’s and thought “every one of these people is gone”? Or from the 1960’s and wondered “what became of them”?

Time steals us all away and leaves photos as proof of existence.

As if answering the question “why do I care,” the poem now plunges into the river of time with its boats and flickering lights and its Heraclitean flow, never captured in art, that leads who knows where. The narrator is having, perhaps, a mini-Whitmanesque moment, crossing the Seine rather than Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, seeing the same boats the slim brunette saw (“steamers”) and the same flickering lights she saw, and knowing now he must not “wrong the moment.”

When the narrator resurfaces, he knows it is important to be “wholly here.” (“Wholly” is such a perfect word!) Across a century, the woman in old Paris has reminded him that we are here but briefly, like the blink of a camera’s shutter. He comes to see that the city of Paris will “welcome us as students trained in her school/ To enjoy the music as much as she did.” Her school? The Music School of the Holy Here.

So wake up, take your present-day companion’s hand, and watch for puddles.

Reading too closely

But there’s a little more to my story about Carl Dennis and Buffalo, New York. Though we might easily have knocked our coffees onto each other’s plaid shirts in the makeshift English Department hallways in, say, 1972, I assumed that 50+ years on, Carl and I had drifted apart to the expected six degrees of separation, or more.

But no, we were a mere two degrees of separation away. Go know! One of the people in the poetry group, Eva, lives in Buffalo. When we read “In Paris” in our group, she said, “Hey, Carl is a neighbor of mine! He lives a couple of houses away.” Wow! So do you know him? “Yeah, of course, but as a neighbor, not as a famous poet.” So cool!

We discussed the poem as a group for a good long time. It felt like we were on that Paris bridge, like we could see the woman in the photograph, like we knew how to be mad at our partners for “wronging the moment” and not being “wholly here” when presence mattered.

But then I pointed out: “look, this poem doesn’t have a period at the end of the last sentence.” It seemed odd to me, and I checked my source for the poem, the Academy of American Poets online. Nope, no period. See for yourself.

What does it mean to leave a poem open-ended like that? Poets don’t do this for no reason, after all. I’m sure I mentioned Emily Dickinson’s defiance of punctuation conventions.

What does the grammatical caesura do in this particular poem?

Does it hint at the continuing, endless nature of Time?

Does it signify something about indeterminacy? but of what? the moment? our relationships?

Are we intended to go back to the start of the poem, like James Joyce made us do in Finnegans Wake (mostly written in Paris!) where the final sentence (“A way a lone a last a loved a long the”) has no period and flows like the River Liffey into the opening sentence (“riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay,”)?

I even checked “In Paris” to see if that worked. It does, if you want it to.

Eva said, “I have an idea! I’ll text Carl and ask!” Fantastic! And she did. “Hey, Carl, we’re reading your poem ‘In Paris!’” And he replied something like I can’t believe anybody’s reading that old poem. And she then asked, “what does it mean that there’s no period at the end?”

And much like Marshall McLuhan, he replied, “That’s a mistake. It’s supposed to be there.”

So much for the River Liffey.

Falling in love

Ok, the sepia-toned woman, so busy with living, “didn’t grieve that she couldn’t stay PERIOD.” Got it. Message to the poem’s speaker from two women, one on the bridge now, one there a hundred years ago: when in Paris, be in love or at least be here now. PERIOD.

“In Paris” was published in Dennis’s 1993 poetry collection The Near World. Unlike the poem’s distracted narrator who was focused on the deep past, the poetry group was reading a modern poem written in our lifetimes. But we were like the narrator in one respect: we were enthralled. We were in Paris, and I think we were falling in love with this poem.

And now, weeks after the poetry group discussion, I find myself re-reading Dennis’s poem umpteen times, poring over it like a man staring at a very old photograph while I’m working on this piece. It’s taken all day, and soon my wife and I have somewhere to be. I hear her call from the other room, “It’s time to go. Enough with that poem already!” I am here and it is now and we do have to go.

Post-script #1

Because the poem above is exactly what I shared with the group, you’ll note there’s no period at the end. Since I have it on good authority that a period belongs there, I’m duty-bound to offer the correct last line: “When she didn’t grieve that she couldn’t stay.” Ah, so much better!

Post-script #2

“In Paris” lead me to Dennis’s books of poetry which are now 14 in total plus one book of essays. I’ve bought several now, including his last, Earthborn. Many colleagues and commenters describe his poetry as thoughtful, sensitive, focused on the everyday, accessible, meditative, humane. All true. But I haven’t found any mention of how funny, how deeply wryly funny, Dennis can be.

In “Primitive,” he refrains from killing a spider in his house in order to avoid the slippery ethical slope toward killing a few people he knows. In “Progressive Health,” he advises healthy organ donors for perfectly ethical reasons not to wait another day before donating their organs. In poems like “Eurydice” and “The God Who Loves You,” you’ll laugh but only to keep from crying. Find them, read them.

The God who loves me whispers that he bets that Carl Dennis likes Groucho Marx and thinks Groucho was a good a preceptor for me in college as any of Carl’s smart colleagues.