Ahmet Haşim and His Poems

On relishing the nightingale’s song rather than killing it for meat

“A poem is not a story; it is a silent song.” — Ahmet Haşim

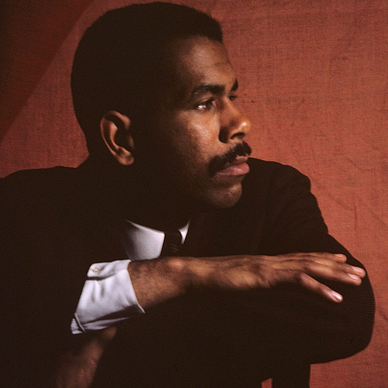

Ahmet Haşim (1887–1933) was one of the great Turkish poets of the early 20th century. Living during the last quarter of the 19th and the first quarter of the 20th century, he witnessed the end of classical Turkish poetry (Divan Poetry) and contributed to the creation of modern Turkish poetry.¹

Haşim’s early work was influenced by such Turkish poets as Tevfik Fikret and Cenap Şahabettin. By contrast, his later work was influenced by French impressionists and symbolists. He is best known for masterfully blending musicality with poetry and using imagery to create strong sensory impressions.²

Haşim was born in Baghdad (then part of the Ottoman Empire), where his father was a provincial governor. After finishing elementary school, he went to Istanbul and enrolled in Galatasaray High School. His mother died in 1906, leaving Haşim broken hearted.

After completing his education, he began to work as a civil servant. Later, he worked as a teacher and translator. He taught mythology at the Istanbul School of Fine Arts and French at the İzmir Sultani. He died in Istanbul in 1933 at the age of 46.

In his short life, Haşim published two poetry collections: Hours of the Lake (Göl Saatleri) in 1921, and The Wine Cup (Piyâle) in 1926. The poems he published in various literary journals prior to these collections were mostly in the classical style. His first collection, Hours of the Lake, already under the influence of impressionism and symbolism, was well received and his peers praised his work.

By the time Haşim published his second collection, The Wine Cup, he had fully transitioned to the modern style. Sadly, The Wine Cup was not well received and some of his peers complained they could not understand the poems in it. He was ridiculed for his poetry, and some of his detractors even accused him of not knowing the Turkish language or the poetic meter required to write good poetry. He was also criticized for not dealing with the concerns of Turkish society.

Haşim’s poems were mostly about loneliness, sadness, death, love, and other personal topics. Under pressure, and as an afterthought, Haşim wrote an introduction for The Wine Cup, in which he described and defended his poetic approach.³ What follows is an excerpt from that introduction:

A poet is neither a reality reporter, nor someone who has perfected eloquent speech to an artistic degree, nor someone who sets restrictions. A poet’s language is not meant to be understood like prose, but rather it should be felt — as an element between words and music, but closer to music than words. The literary elements used in prose to create a narrative are totally unsuitable for poetry. Prose gives birth to reason and logic, whereas poetry, with the exception of those parts dealing with perceptions, is a nameless spring. It is buried in secrecy and obscurity. A poet’s language may be understood only at the edges of his half-lit perceptions. Scrutinizing a poem to find its meaning is like killing a poor nightingale, whose songs are capable of giving goosebumps to even a summer night’s stars, for its meat. Can that morsel of meat fill the place of the beautiful voice which is silenced? What’s important in poetry is not the meaning of a word but how it is used. Those who think poetry is a shared language are only dreaming.

His introduction did little to satisfy his critics, but he did have an important admirer: his fellow Turkish poet, Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, who was not yet famous. Tanpınar was 14 years younger than Haşim, and after Haşim’s untimely death, Tanpınar filled his vacant seat as an art history teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul.

Interestingly, Tanpınar’s own poetic aesthetic is closer to Haşim’s than any other Turkish poet. Both men considered musicality to be the most important aspect of their poems and were focused more on the feelings their poems evoked in the reader than the meaning of the words they used. After Haşim’s death Tanpınar wrote the following:

In Ahmet Haşim, we met for the first time with a truly great poet as defined by the Western school of thought (i.e., the Europeans). We learned from him that, behind a poem, it is necessary to have a whole world of aesthetics and structure. In this respect, the introduction Haşim wrote for The Wine Cup, which was published in Dergâh, was a real turning point for Turkish poetry. There are two kinds of poets. The first is one who is naturally inspired in a way that the general public is inclined to approve and enjoy — the man who weaves in his magic whatever the days and moments bring to him. The second is the exact opposite. He does not tolerate any external interference in his poems. Their understanding of poetry is not the result of any external stimuli, but the product of voluntary, intelligent effort. Ahmet Haşim was this second kind. He gently sang, in his own way, of a world he created with his own willpower and intelligent efforts.⁴

To get better acquainted with Haşim’s poetry, we’ll look at five of his poems. Through these poems we’ll observe the transformation in his poetic style as he progressed from the classical to the impressionist approaches. “The Garden (or, Remembrance)” is from his first collection and is somewhat still within the norms of the classical style.

The poem describes a garden at sunset. The last ochre rays of the sun bring a gentle beauty to the garden, giving it a resemblance to the famous Persian gardens or those colorful gardens typically found on prayer rugs. The same rays reflect on the pool too, making it look as if it were full of red wine. Next, the poet says that during this time of day, his beloved looks uncharacteristically somber. He concludes by saying that the only joy left in later life is remembering the beautiful days of the past. The poet uses the setting sun as a metaphor for the end of life — a departure from a doom-filled world.

The next poem, “The Nightingale,” is from Haşim’s second collection, The Wine Cup.

The poet clearly alludes to the end of summer, and at this time, classical Turkish poetry’s most cherished bird, the nightingale, is in love with a rose. The end of summer brings an end to the blooming rose, an event the nightingale mourns.

When we examine the poem more closely, a deeper meaning emerges. Haşim is actually alluding to classical Turkish poetry, which at the time was undergoing a metamorphosis. Hence, the nightingale in the poem symbolizes a poem in the classical style.

The verse before the last, “That rose is now scattering in the air” is a reference to how that style is fading away fast. The last verse, “At a different star, the sun is rising there,” refers to the transition into a new literary era — away from the Eastern style toward a Western style. Thus, the poem’s secondary and perhaps more important theme is “out with the old, and in with the new” and the sadness associated with that change.

Stretching it a little further, one could interpret the poem as a reference to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the creation of the Turkish Republic — which took place in 1923, just three years before the publication of The Wine Cup. In short, the poet is expressing his feelings of nostalgia for what is being left behind.

The third poem, “A Wish at the end of a Day,” is considered one of Haşim’s best in The Wine Cup. It features characteristics unprecedented in Turkish poetry at the time.

Haşim said the following about this poem: “My most beautiful poem, and I am afraid, my only beautiful poem. That’s the truth. The others are all child’s play, quite rudimentary!” In this poem, Haşim takes the impressionistic approach to poetry to a whole new level, and revels in the structural freedom offered by the modern style.

The poem starts at sunrise and ends at sunset. To depict the diminishing daylight during this time, Haşim uses a decreasing number of verses in successive stanzas, starting with 5 and ending with 2. Turning from physical appearance to meaning, again he uses words to paint an image. In the first stanza, he says the sun’s ascent appears to him like roses, alluding to the similarity between the typical red colors of sunrise and roses.

In the second stanza he suggests that, contrary to general belief, at night birds leave our world and travel elsewhere. He sounds envious. In the next stanza, he draws a clear image consisting of a golden horizontal line ahead and a bow above, reminiscent of an archer. Then he completes the image by saying he wishes he were a reed — a straight line perpendicular to earth, like an arrow — meaning he wishes to leave the earth like an arrow shot from a bow. That is his “wish.”

The next poem, “The Wine Cup,” is from Haşim’s second poetry collection with the same title. It is one of his most famous poems and though it may appear, on first glance, to be an ordinary love poem, it is about the love of God.

The last poem we will look at is Haşim’s “The Carnation,” which is reminiscent of a Haiku in style and has the same theme as the previous poem, the love of God.

In closing, it is safe to say Haşim has a special place in Turkish poetry. No doubt, some of his poems will not go out of style any time soon, no matter what the latest literary trend is. I will end with a few wise words from Haşim: “Nothing is more similar to trees than languages. Languages — just like trees — shed their dead leaves from time to time and grow fresh ones. The leaves of languages are words.”

Notes

¹ Divan is the name of the classical style used in Turkish poetry for many centuries. Developed under the influence of Eastern poetry, it is highly structured, with rigid rules and without much room for flexibility. Beginning with the declaration of the Constitution in 1908, the classical style was slowly replaced with a new style influenced by Western poetry.

² When translating poetry, it is not possible to render the same level of musicality and structure in the target language as the source language. Therefore, some descriptions in this essay apply only to the original Turkish versions of the poems, not the translated versions.

³ The introduction Haşim wrote for The Wine Cup is entitled “A Few Remarks About Poetry” (in Turkish, “Şiir Hakkında Bazı Mülahazalar”).

⁴ “Akşam Şairi: Ahmet Haşim,” Anadolu Ajansı (3 June 2020).

* The poems included in this essay were translated into English by the author.