An Urdu Poet on the Palestinian Liberation Struggle

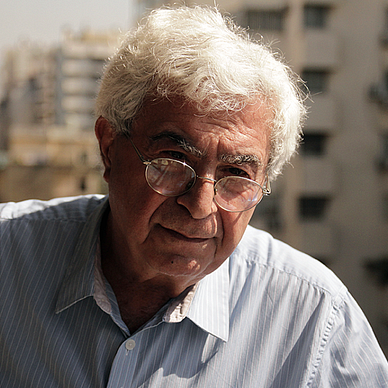

Faiz Ahmed Faiz on the martyrs of Palestine

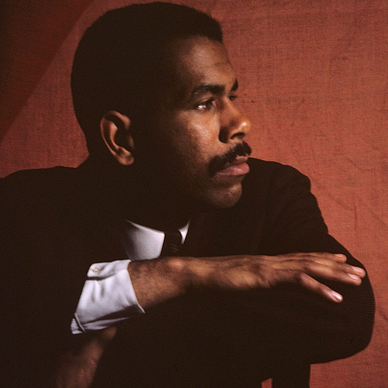

In Memory for Forgetfulness (1987) by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, we encounter a self-exiled Faiz Ahmed Faiz living in a city deeply scarred by conflict. It is Beirut in the late 1970s. Having escaped the military dictatorship of General Ziaul Haq after Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in Pakistan, Faiz finds himself amidst an entirely new political struggle.

As a revolutionary poet, Faiz could not escape resistance movements and was always at the heart of liberation struggles. While this was no longer Karachi and the fight for freedom came at an entirely new cost, Faiz was adept at seeing the shared humanity which underscores much of his poetry.

In his book, Darwish reflects on how Faiz (spelled below as Fayiz) was busy with the question of the artist:

“Where are the artists?”

“Which artists, Fayiz?” I ask.

“The artists of Beirut.”

“What do you want from them?”

“To draw this war on the walls of the city.”

“What’s come over you?” I exclaim. “Don’t you see the walls tumbling?

This exchange powerfully conveys the complex role of artists in times of conflict. Faiz was greatly preoccupied with this role and explored it throughout his literary career. Faiz longs for the artist to document and interpret the war, to “draw this war on the walls of the city,” as a means of bearing witness to the suffering and resilience of the people. He sees art as a vital tool of resistance, a way to capture and preserve human experience amidst the chaos.

Darwish grounded in the harsh reality of Beirut’s destruction, Darwish points out the seeming futility of such an endeavour when the very walls that could bear this art are literally crumbling under the weight of the ongoing violence.

Through this dialogue, Darwish and Faiz highlight the critical need for literature and art as voices of resistance. Faiz illustrates the artist’s unique role in making sense of suffering, capturing the resilience of the human spirit, and ensuring that the stories of those caught in conflict are not lost to the ravages of war.

Even as the walls crumble, the need to document, to bear witness, and to resist through art remains as crucial as ever.

Editor in exile

Faiz Ahmad Faiz, a name synonymous with resistance, justice, and humanism, was a renowned Pakistani revolutionary poet whose verses transcended borders and spoke to the universal struggles of the oppressed.

Known for his deep emotional connection to humanity, Faiz’s poetry intertwined the personal with the political, often blurring the lines between love and sorrow, beauty and despair. His life and work were a testament to his unwavering commitment to speaking truth to power, a commitment that led him into exile in Beirut during one of the most tumultuous periods in the city’s history.

The 67-year-old poet chose self-imposed exile in Beirut in 1978 after facing increasing risks in Pakistan due to the military dictatorship of General Zia ul-Haq. Having been previously imprisoned from 1951 to 1955 on charges of conspiring to overthrow the government, Faiz lived under the continuous threat of re-arrest.

Yet, Beirut was a precarious refuge. At that time, Lebanon was engulfed in a brutal civil war that would span 12 years. Beirut, divided by the infamous Green Line which separated the Christian-controlled East from the Muslim-controlled West, was a focal point of intense conflict, where daily life was punctuated by the constant threat of raids.

Despite the city’s dangers, Beirut was a hub of modern Arabic culture and anti-imperialist thought. Committed to international solidarity, Faiz quickly found his place: where art, politics, and resistance were inextricably linked.

Faiz became the first non-Arab editor of Lotus, a trilingual quarterly magazine issued by the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association (AAWA). The magazine was funded by the Soviet Union, Egypt, East Germany, and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO). His editorial role was facilitated by his close ties with Yasser Arafat and Mahmoud Darwish.

As the editor of Lotus, Faiz played a pivotal role in ensuring that the magazine served as a powerful platform for writers from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East to express their struggles against colonialism, occupation, and dictatorship. His editorial work reflected his deep belief in the power of literature to inspire and mobilise the oppressed. He also contributed poetry, translated works, and essays—including pieces like “The Role of the Artist”—to the magazine.

However, Faiz’s time in Beirut was brief. Less than four years later, he was yet again forced to flee. In 1982, with the Israeli siege of the city, Faiz and his wife were compelled to return to Lahore. He continued to edit Lotus from afar and was last listed as editor-in-chief in issue 56, published after his death in November 1984.

Faiz and the Palestinian liberation struggle

Faiz’s exile in Beirut deepened his connection to the Palestinian cause and offered him a platform from which to voice his solidarity. His poetry, already steeped in themes of resistance, gained new depth and relevance in the context of the Palestinian struggle.

While in Beirut, Faiz penned two powerful poems in support of the Palestinian cause: “Palestinian Martyrs in Foreign Lands” and “Lullaby for a Palestinian Child.” These poems were later included in his 1980 collection Mere Dil Mere Musafir (My Heart, My Traveler), which he dedicated to Yasser Arafat.

In “Palestinian Martyrs in Foreign Lands,” Faiz mourns the loss of Palestinian freedom fighters who sacrificed their lives far from their homeland. The poem is a profound meditation on the sorrow of exile, capturing the deep pain of longing for one's homeland.

Yet, amid the loss and mourning, there is a powerful undercurrent of pride and defiance. Faiz honours the resilience of those who continue to resist oppression, even when the odds are overwhelmingly against them.

I translate the poems below.

Palestinian Martyrs Who Were Slain in Foreign Lands

Wherever I went, O homeland,

The painful scars of your humiliation I carried in my heart,

The desire for the light of your dignity I carried in my heart,

The yearning of your love, your memory accompanied me,

The fragrance of your orange blossoms accompanied me,

The glow of all the unseen companions remained with me,

How many hands were embraced in mine

In the unkind paths of distant foreign lands.

On the paths of unnamed streets of unfamiliar cities

On the land where my blood blossomed as a standard

There waves the flag of Palestine.

Your tyranny destroyed one Palestine,

My wounds how many Palestines established

(my translation of the original Urdu)

Faiz employs the classical ghazal form to intensify the emotional resonance of his reflections. Rooted in Urdu and Persian literary traditions, the ghazal traditionally delves into themes of love, loss, and longing — motifs that echo profoundly with the Palestinian struggle for identity and homeland. The structure, comprising independent yet thematically intertwined couplets, mirrors the fragmented existence of those affected by the Palestinian cause, whether displaced by conflict or living in exile. Yet, these dispersed lives are unified by their collective fight for freedom, much like the overarching theme in a ghazal binds the individual couplets.

The recurring refrains of the form also generate a rhythmic persistence, symbolising the unwavering spirit of the Palestinian people, whose resilience intensifies with each act of oppression. As a Marxist, Faiz reinterpreted the ghazal’s traditional themes of love and mystical yearning, transforming them into a broader political message that calls for justice and liberation. Blending the classical form with political struggles, Faiz emphasizes that love and resistance are intertwined and that the fight for a just world is as sacred as any mystical pursuit.

This poem shows show that attempts to destroy Palestine only lead to the strengthening of its spirit and identity. The wounds inflicted by oppression and violence do not lead to the erasure of the Palestinian cause; instead, they give birth to countless new “Palestines,” each one a testament to the enduring resilience and determination of the people.

Faiz shows that the struggle for freedom cannot be quelled by physical force; instead, it is a movement that grows stronger with each attempt to suppress it. The wounds of the people become sources of strength that carry forward the fight for justice and freedom.

In 1980, Faiz also wrote a poignant lullaby (here is a clip of him reading it) in response to the devastating attacks on Palestinian camps in Beirut by Israeli gunships.

A lullaby for the Palestinian child

Don’t cry child,

Don’t cry child,

Crying and crying,

Your mother just fell asleep,

Don’t cry, child,

Moments ago,your father,

took leave from his sorrows,

Don’t cry, child,

Your brother,

chasing his butterfly dreams,

has gone off to a faraway land,

Don’t cry, child,

Your sister’s wedding carriage,

has gone to a foreign place,

Don’t cry, child,

in your courtyard,

the dead sun has been washed,

the moon has been buried

Don’t cry, child,

For if you do, then all of these —

your mother, father, brother, and sister,

the moon and the sun —

will make you weep all the more.

Should you smile instead,

then perhaps in a different form,

they will all return to play with you one day

(my translation from the original Urdu).

What resonates most deeply in this poem is the profound suffering that innocent children have endured since the onset of the Palestinian struggle for freedom. The repeated refrain ‘Don’t cry, child,’ underscores how it is children who continue to bear witness to the harsh realities of the occupation.

For children who experience the loss of loved ones and any sense of a true homeland, their shattered dreams leave them with little hope for a better future. It is children who, despite carrying the traumatic burden of memories must learn to ‘smile instead.’

However, Faiz also offers a glimmer of hope in the face of all the irrevocable loss. The final lines call on them to find resilience and patience so that the days of joy and peace might once again return, though ‘in a different form.’

A lasting symbol of resistance and a beacon of hope

Nearly five decades later, Faiz’s poetry remains as relevant as ever and continues to resonate deeply amidst the unrelenting tragedy of the ongoing genocide and occupation of Palestine. Faiz’s call for the presence of artists — whose voices capture the suffering as well as offer hope — has never been more urgent.

Through these poems, Faiz not only expressed his solidarity with the Palestinian cause but also underscored his belief in our shared humanity. Nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature and awarded the Lenin Peace Prize, Faiz’s poetry serves as a powerful vehicle for empathy and a strong critique of the dehumanisation inherent in conflict. His work remains a lasting symbol of resistance and a beacon of hope.