The Fisherman of Halicarnassus

How Turkish writer Cevat Şakir continued the tradition of Homer and Herodotus

When visitors arrive in Bodrum (Halicarnassus, during ancient times), they are greeted by a conspicuous sign on the summit of a hill that reads:

When you reach the top of the hill, you will see Bodrum. Don’t assume that you will leave as you came. Others before you were the same too. As they departed, they all left their souls behind.

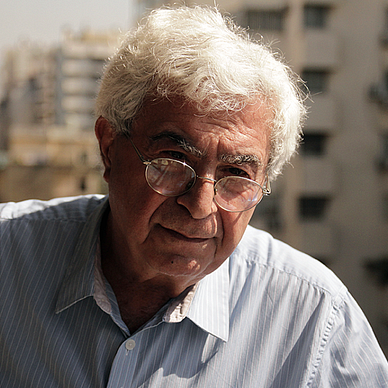

These are the words of Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı (1886–1973), a prominent Turkish author who, in 1925, was exiled to Bodrum for three years because of an article he wrote criticizing the government. Back then, Bodrum — located on the Aegean coast of Turkey — was a small fishing and sponge-diving town.

While Cevat Şakir was there, living under fairly relaxed conditions, he fell in love with the entire region. The beauty of the scenery, the rich history of the region, the warmth of the people, their customs and culture, but above all, their way of life captivated him completely. After finishing his sentence — spending only the first year and a half in Bodrum, and the rest in Istanbul — he returned to Bodrum and spent the rest of his life there.

He adopted the pen name “The Fisherman of Halicarnassus” and began writing exclusively under that name. Cevat Şakir was a prolific writer and, when he died in 1973, he left behind many novels, collections of short stories, investigative writing, and essays, mostly related to the natural beauty of Bodrum and the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts of Turkey (known as Lycia in ancient times).

Cevat Şakir also contributed greatly to the literary discourse of the time by translating nearly 100 books from various languages (he was fluent in nine) into Turkish.¹ In 1971, two years before his death, the Turkish government recognized Cevat Şakir’s extraordinary contributions by presenting him with the prestigious State Culture Award.

Born into a well-to-do family, Cevat Şakir was a historian educated at Oxford University, where he earned a degree in Modern History. After graduating from Oxford in 1911, he moved to Rome and studied painting at the Academy of the Fine Arts. During this time, he married an Italian woman.

In 1913, Cevat Şakir returned to Turkey and began writing columns in the newspapers and literary journals. Apart from his reputation as a prolific writer, Cevat Şakir is better known as a humanist and naturalist. Throughout his life, he worked tirelessly for marine conservation in and around Bodrum and helped establish top-quality ecotourism facilities in that region. Cevat Şakir’s writing has been largely credited for introducing Bodrum to the world and making it a top international tourist attraction. He is one of the founders of the very popular Blue Cruise offerings in that region.

The following quote from Cevat Şakir eloquently expresses his devotion to, and love for, the Bodrum region:

Take a blind man to Lycia, and he’ll immediately know from the smell of the air exactly where he is. The acrid perfume of lavender, the pungent fragrance of wild mint and thyme, will tell him.

His life philosophy often reflected in his stories is that people who live closely connected to nature are a lot happier than those who don’t.

As an author, Cevat Şakir’s writing style is quite lyrical, almost poetic. The sea — either the Aegean or the Mediterranean — is usually central to his stories, and his protagonists are people who make their living off the sea.

Meanwhile, those who do not work hard to reap the sea’s harvest, and instead live idle, luxurious lives, are depicted as adversaries exploiting the heroes of the stories. However, these antagonists are always individuals and never a class of people. In this way, the author ensures that his stories steer clear of politics and are not misinterpreted.²

Today, some literary critics, while acknowledging the power and appeal of Cevat Şakir’s lyrical style and epic narratives, argue that, from a technical standpoint, his writing is less than perfect.

Their argument is based on three factors. First, the author’s frequent use of very long and complex sentences is deemed to be unnatural in Turkish. Second, his tendency to use technical terms and terminology borrowed from Greek mythology as well as from other local legends is considered to diminish the purity of his writing in Turkish. Third, it is argued that the author’s reliance on highly lyrical and often exuberant language is done at the expense of a proper literary style, for which he pays the price.

Perhaps the easiest way to illustrate the author’s somewhat unique literary style, especially for those unfamiliar with his work, is to present short extracts from a few of his best loved stories. Here are three such extracts:

The Bird that Lost the Light tells the dramatic story of a mother seagull (Miho), who is shot and blinded by a ruthless hunter. Describing Miho’s struggle to stay alive, many hours after she was shot, he writes:

She flew several more hours. By then, night had fallen. The Miho was still searching for daylight but could not find it. Her wings were getting heavier. She realized she would not be able to reach daylight with her wings. Instead, she began to search the blue sky with her voice. With her innocent voice, she started to sing a song. With her song and the fire burning inside her, she tried to create a new sun that would shine light and bring an end to this terrible darkness. But she was exhausted, and soon her voice began to waver.³

Mermaid Island recounts a grandfather’s deep love of the sea and his pleasant memories of fishing and diving in his younger years. Describing the grandfather’s encounter with a ‘mermaid,’ he writes:

I had fallen completely in love. I dived! I followed her! Night fell. She, blinking brightly, was swimming away. She dived; I dived. She came to the surface; I came to the surface. She swam; I swam. I do not know how many times we circled the island. She was laughing and smiling. Her laughter was biting and infectious, like the salt of the sea. The moon was up; and it was huge. My eyes, opened wide, beheld a pure white light. It was perfectly circular! I could not tell if it was the moon, the island, her, or me moving. I was repeatedly reaching out to touch her. Each time she looked at me, I saw the moonlight in her eyes. One moment she was disintegrating into bits and pieces, the next, she was coming together like mercury. Finally, I was able to wrap my arms around her waist. I tried to embrace her, but she instantly melted away. It was only the moonlight I was embracing.⁴

Maneuver is a story of several fishermen and their boats, caught in a vicious storm at sea, and their struggle to survive. Describing one captain’s courageous rescue of four fellow fishermen from the sea after their boat capsizes, he writes:

The Denizkuşu moved toward the Martı like an arrow shot from a bow. Each time the wind hit, the whole armada crackled like the bones of imprisoned men being tortured to death. When they were five meters from the Martı, Ateşoğlu screamed, “Lower the sails!” The Martı crested a huge wave. Just as the wave was about to fall, Ateşoğlu yelled, “Hoist the sails!” The boat’s yard was tossed in the air. Reaching into the sky, the sails were nearly shredded. Like a race horse being whipped, the Denizkuşu took off, nose up, flying over the Martı from its side against the wave as Ateşoğlu yelled, “Take them in!” The crew reached out, over the railings and down to their waists, to pull their friends, grabbing their arms, their hair, and their chins — anything they could get a hold of. They swept them aboard as if emptying their daily catch of fish into the depository. Like swallows circling over a pool of water, pausing to quickly gulp in the water while still in flight, the Denizkuşu had plucked four men from the sea.⁵

It is interesting to note how the author uses very little dialog in some of his stories, and yet, he is still able to create powerful and likeable characters. Despite the limited discourse in these stories, the reader has no difficulty relating to his characters; and when warranted, feeling empathy for their troubles. No doubt, this is achieved by the author’s skilful storytelling.

Indeed, notwithstanding the few suggested deficiencies in Cevat Şakir’s literary style, the Fisherman of Halicarnassus was a highly gifted and skilled storyteller who left behind many wonderful tales. The substantial contributions he made to the Bodrum region, as well as to Turkish literature will always be remembered with respect and gratitude.

Azra Erhat, one of Turkey’s most prominent intellectuals of that generation, gave Cevat Şakir an exceptional accolade when she famously said, “Three major figures helped elucidate the history of Anatolia. These were Homer, Herodotus and the Fisherman of Halicarnassus.”

No doubt, if these three great minds of modern and ancient history were together in the Fisherman of Halicarnassus’ boat off the Aegean coast, they would cast their lines deep into a philosophical discourse on humankind, the beauty of nature, and the art of fishing.

Notes

¹ In addition to Turkish, Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı was fluent in Arabic, Persian, English, French, Italian, German, Greek, and ancient Greek.

² Halikarnas Balıkçısı’nda Doğa (The Fisherman of Halicarnassus and Nature) by Selim İleri, 1976.

³ Gündüzünü Kaybeden Kuş (Halikarnas Balıkçısı, Merhaba Akdeniz, 1962).

⁴ Denizkızı Adası (Halikarnas Balıkçısı, Merhaba Akdeniz, 1962).

⁵ Manevra (Yaşasın Deniz, 1954).

The story extracts appearing in this essay were translated from Turkish into English by the author.