The Tanpınar Challenge

How to translate poetry that defies translation

Note from the editor Rebecca Ruth Gould, PhD

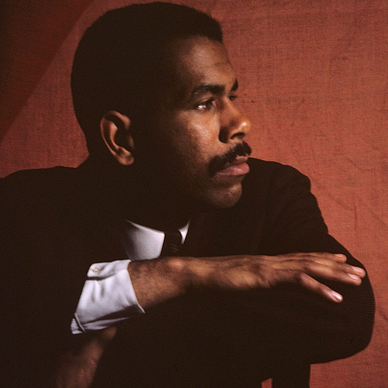

Here at GLT, we’re very excited to introduce you to a series of translations of Turkish literature by the eminent Turkish-English translator, Aysel K. Basci. We have already published one story in this series, Basci’s translation of “The Dog” by Sabahattin Ali.

Before proceeding with our next stories in this series, which are by the masterful Turkish writer Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, we wanted to give Basci the opportunity to explain her translational method to our readers. The essay below focuses on Basci’s approach to translating Tanpınar’s poetry but it also illuminates her translations of Tanpınar’s prose which we will be publishing soon.

General guidelines exist for literary translators to follow, but it is also common for individual translators to have their own set of principles developed over time based on their experience. I fall in this second category and follow a few simple rules of my own.

When I am translating straight prose, I focus on two things. First, when creating the translated text, I try to remain as true to the author’s voice and intended meaning as possible. Second, to the extent I am able, I try to ensure that the reader is as unaware as possible that he or she is reading a translation. Sometimes these requirements conflict with each other, requiring some give-and-take between them.

When translating poetry, I consider two additional factors. First, if the poem is to be translated rhymes, I assess whether the translation should also rhyme or not. Second, if aesthetics were important to the poet, I evaluate whether it is necessary — or even possible — to take this into account and achieve pleasing aesthetics in the translated poem as well. Choosing to utilize a rhyming structure and attempting to create pleasing aesthetics are at the discretion of the translator, but because these features are so difficult to achieve, they are usually ignored.

What makes translating the much-respected Turkish poet and author Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar’s poetry so daunting is that these latter considerations cannot be easily ignored. Doing so takes too much away from his art.

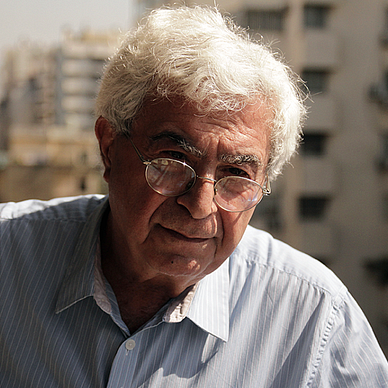

Tanpınar (1901–1962) was a Turkish poet, novelist, literary scholar and essayist, widely regarded as one of the most important representatives of modernism in Turkish literature. He was a professor of aesthetics, mythology and literature at the University of Istanbul. Although he died 62 years ago, his writing and poetry remain very popular among Turkish readers today.

When translating Tanpınar’s poetry, one must be prepared to work with four competing considerations: reflecting the true meaning of his words, sounding natural in the translated language, rhyming, and providing pleasing aesthetics. Perhaps such difficulties are the reason why, thus far, very few of Tanpınar’s poems have been translated.

In his verses, Tanpınar chooses his words with extreme care and quite sparingly — the fewer, the better. His word choice is simple, yet impeccable. Reflecting the accurate meaning of his words in a different language is incredibly challenging.

In most (although not all) of his poems, Tanpınar uses rhyme and meter abundantly and to great effect. To render some sense of his art into the translated work, the translator is almost obligated to use rhyme.

Tanpınar cared deeply about aesthetics, and constructed his stanzas with the utmost care. They are perfectly engineered and precise. So, ideally, his focus on aesthetics should be reflected in the translated poem as well. However, in practice, this is nearly impossible to do.

Above all, Tanpınar’s poems exhibit an overall elegance that permeates his verses and stanzas, which cannot be easily rendered in a different language — not because the translator lacks the skills to do so, but because of the intrinsic differences in the source and target languages. Some concepts, expressions, or even points of view are simply not perfectly translatable. Therefore, the translator has no choice but to settle with what is available.

For these reasons, translating Tanpınar’s poetry is intimidating, and the effort required to do it effectively and accurately should not be underestimated. Furthermore, it should be understood that the results will probably never be perfect (or even near perfect). Therefore, it is wise to set low expectations for the results to help mitigate potential disappointments.

Thus, it is fair to say that translated poems are not always art. Sometimes, they are just a translation into a different language of what the poet conveyed and nothing more. Ontological analysis, and other tools, exist to help measure the artistic values of poems.

For poets like Tanpınar — an extraordinarily gifted artist — it should not be a surprise if those values differ markedly between the original work and the translation. This doesn’t mean there aren’t gifted and highly skilled poets who are capable of fully rendering Tanpınar’s art in a new language, but the task is difficult.

Case Study: “The Ship Asleep at the Dock”

Where possible, I eliminated as many words as I could from the translation.

Below, I use Tanpınar’s poem “The Ship Asleep at the Dock” — heavily rhymed, meticulously timed, and aesthetically crafted to perfection — as a sample to illustrate the challenges involved in translating it as well as the mediocrity of the result. What follows describe the nuts and bolts of the process. Not everyone may be interested in these technical details.

In translating poetry, I follow two steps. First, I do a substantive analysis of the poem, which involves a close reading (and many rereadings) to analyze its structure and identify potential difficulties. For this step, the sample poem did not present many difficulties.

Next, I follow a fairly analytical process comprising three stages. First, I translate the poem as if it were straight prose, focusing on capturing the poet’s ideas. Second, I try to rhyme the translated poem. Finally, I try to improve the aesthetics of the translated poem, knowing that there may be little I can do. Below are the sample and the translated poems.

Theme: The theme of the poem is ‘longing to reach eternity.’ The subject is a retired ship resting (asleep) at a dock. The poet relates this ship to his own, old and tired state-of-mind which is consoled only with past memories. By trying to wake up the ship, the poet expresses his longing for his younger, more vibrant days.

He also sees a parallel between the ship’s struggle with sea and his own struggle with life. To the poet, open seas signify eternity, and his wish to sail in the ship to the open seas expresses his desire to reach eternity (death). At the end of the poem, he realizes this is impossible and returns to reality. He concludes that going back to his younger days is not possible.

Rhyming: The sample poem features assonants, full and triple rhymes. My earlier analysis revealed that, in the translation, this level of rhyming would not be possible, so I tried to do the best I could. I had to make several compromises, such as changing the order of some phrases, exchanging some words with their synonyms, and modifying the structure of a few sentences. Despite my effort, the two last quatrains feature only near-rhymes.

Timing: The sample poem is an octameter (8 syllables per verse, with no pauses). The translation could not be perfectly timed and contains verses with a varying number of syllables.

Style and Aesthetics: Tanpınar preferred to use as few words as possible. Where possible, I eliminated as many words as I could from the translation. In this stage, it was the only improvement I could do. I categorize these changes as style, not aesthetics.

The aesthetic appeal of Tanpınar’s poems is far more ambitious, which is why translating his poems is difficult! Tanpınar was taught aesthetics by the great Turkish poet Yahya Kemal Beyaltı, and he taught the subject (which was dear to his heart) at Istanbul University for many years. More than once Tanpınar complained about the slowness of his output — undoubtedly due to his perfectionist approach to aesthetics.¹

Let’s delve into Tanpınar’s aesthetic considerations. He saw a poem as a four-layered construction forming a whole. The whole needed to be appealing while each layer contributed to the overall pleasing aesthetics. The four layers are as follows:

Sound of words: He chose his words such that the sound of each word contributed to the overall music of the poem in a pleasing manner. He ably used meter, rhyme, repeated voice, assonance, and alliteration techniques to achieve the desired result.

Meaning of words: He used words with both explicit and more subtle, hidden meanings (which one could grasp by reading between the lines and considering the totality of the poem).

Imagery of words: He carefully chose objects that helped create vivid mental imagery (such as open seas, stern waves, roaring waters, torn sails, breeze of the morning).

Feeling of words: This refers to the feelings evoked individually and collectively by the objects mentioned in the poem. In Tanpınar’s case, this could also be called “the fate of the poem’s objects.”² This fate is not explicitly spelled out, but implied by using “us” and “we” instead of “I.” Thus, whatever fate the poem describes is shared by all and, therefore, of direct concern to the reader. This approach evokes the reader’s emotions.

Even though the beauty of Tanpınar’s original poem is not fully reproduced in this initial translation, by attending to these literary techniques and devices which are unique to Tanpınar’s poetics, translators can improve their craft. The same approach can be used for other poets: the better translators understand their poet’s aesthetics, the more likely they are to give birth to poems that rival the original in translation.

References

¹ Hüsrev Akın, Analysis of Tanpinar’s Poems with Ontological Method (2016).

² İsmail Tunalı, Sanat Ontolojisi, İnkılap Yayınları (2002).