Raga and Dwesha: Key Concepts in Yoga You Should Know

Buddha, Krishna, and Patanjali on the important concepts of Raga and Dwesha (— Attraction and Aversion)

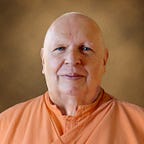

by Abbot George Burke (Swami Nirmalananda Giri)

Two of the most important words in analyzing the dilemma of the human condition are Raga and Dwesha–the powerful duo that motivate virtually all human endeavor. Buddha, in common with all philosophers of India, continually refers to them, so an understanding of their import is essential to us.

Unfortunately, both Hindu and Buddhist translators are prone to do just that–translate them–and thus obscure or distort their meaning. There may be exact equivalents in other languages, but NOT in English, and translators do us a real disservice by not retaining them and explaining them somewhere in the text, by a footnote, or by a glossary. Here is my preferred definition of them:

Raga: Attachment/affinity for something, implying a desire for that. This can be emotional (instinctual) or intellectual. It may range from simple liking or preference to intense desire and attraction.

Dwesha: Aversion/avoidance for something, implying a dislike for that. This can be emotional (instinctual) or intellectual. It may range from simple nonpreference to intense repulsion, antipathy and even hatred.

They are commonly referred to as “rag-dwesh”–as a duality, for they are the alternating currents or poles that keep us spinning in relativity, reaching out and pushing away, accepting and rejecting, running toward and running away from. The horror of them is that they not only alternate, spinning us around, they also mutate into one another. What we like at one time we dislike at another, and vice versa. For they, like everything else, are essentially one, a double-headed monster.

“When he has no lust [raga], no hatred [dwesha],

A man walks safely among the things of lust and hatred.

To obey the Atman

Is his peaceful joy;

Sorrow melts

Into that clear peace:

His quiet mind

Is soon established in peace.” (Bhagavad Gita 2:64,65)Buddha lists ridding ourselves of raga and dwesha as the first step in the Holy Life. But what a gigantic step! It will not be made overnight, we may be sure, for raga and dwesha have driven us along from the moment we were plants, what to say of animals and human beings.

Raga and Dwesha in the Bhagavad Gita

However, with attraction and aversion eliminated, even though moving amongst objects of sense, by self-restraint, the self-controlled attains tranquility (Bhagavad Gita 2:64).

The words translated “desire” and “hatred” are raga and dwesha. Raga is both emotional (instinctual) and intellectual desire. It may range from simple liking or preference to intense desire and attraction. Dwesha is the opposite. It is aversion/avoidance in relation to an object, implying dislike. This, too, can be emotional (instinctual) or intellectual, ranging from simple non-preference to intense repulsion, antipathy and even hatred.

We must keep in mind that anything can grow and change. Therefore simple liking can develop into intense craving, and mild dislike can turn into intense aversion or hatred. And since opposites are intrinsically linked to one another and can even turn into one another, the philosophical and yogic texts frequently speak of raga-dwesha, the continual cycling back and forth between desire/aversion and like/dislike.

Obviously, this makes for a confused and fragmented life and mind, something from which any sensible person would wish to extricate himself.

Finding the right cure

There are a multitude of supposed cures for what ails us. The vast majority do not work because they are not really aimed at what truly ails us. The rest usually do not work because they are based on a miscomprehension of the nature of the problem, or because they are simply nonsensical and time-wasters. This is true of most religion and of a great deal that is called yoga [see the article What is Yoga?].

If we look at this verse we discover that Krishna is speaking of a very real inner state in which the individual is utterly free–and incapable–of raga and dwesha, and not just a psychological alteration coming from insight into or analysis of the defects of addicting objects. In fact, just the opposite will happen, for “thinking about sense-objects will attach you to sense-objects,” as we considered previously. This is a law, and we will be wise to keep it in mind.

There is no use in trying to talk ourselves out of delusion. We must dispel delusion–not by concentrating on delusion or resisting it, but by attaining jnana: spiritual knowledge coming from our own direct experience. This will dissolve delusion automatically.

Therefore, when we are no longer subject to attraction and aversion for objects, we can move among them without being influenced or moved in any way. But we must be very sure that we truly are no longer susceptible to them, and not just going through a temporary period in which we find ourselves indifferent to them. Such periods are sure to end in re-emergence of passions that in the meantime have grown even stronger within us. Many ascetics have been deluded in this way, so we must be careful.

Raising our Consciousness beyond raga and dwesha

I have left the most important for last. The Sanskrit has atmavyashyair vidheyatma: “having controlled himself by Self-restraint.” [See A Brief Sanskrit Glossary] That is, he has controlled his lower self by moving his consciousness into the higher Self. Until he does so, the lower self drags the higher Self along from birth to birth. But when the higher Self comes into control of the lower self the situation is different indeed.

Atmic consciousness alone is the antidote to all our ills. When the sadhaka no longer acts according to intellectual or instinctual motives, but rather is living out in the objective world the inner life of his Self, then and only then is true peace gained by him.

Acting out of intellectual belief, faith, devotion, or even spiritual aspiration, can certainly elevate us, but ultimate peace cannot be found until, centered in the Self, we live our life as a manifestation of Spirit. It was the Self speaking through Jesus that gave the invitation:

“Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28–30).When the buddhi rests in the Atman, peace is inevitable. That is what a Master really is: one who lives ever in his Self. Everything else needful follows as a matter of course. And how can this come about? Krishna tells us clearly in the next verse.

In tranquility the cessation of all sorrows is produced for him. Truly, for the tranquil-minded the buddhi immediately becomes steady (Bhagavad Gita 2:65).

Note that the cessation of sorrows is not bestowed on the buddhi yogi, nor does he acquire it. Rather, it is produced, it evolves, it grows like an embryo. First is conception, then growth and then birth. It is a process that goes in stages.

It does not come like a lightning strike, but slowly and in an orderly manner, for it is a natural consequence of the yogi’s unfoldment through sadhana of his essential nature. It is evolution, not revolution.

This is why the idea of instant enlightenment, of instant liberation, springs from ignorance of the way things are. For the state of liberation through Self-realization is a revelation of the way things have always been. This is the real non-dual teaching of the Gita. The steadiness of the buddhi comes immediately upon the birth, but the birth takes time. That is what buddhi yoga is all about–coming to birth, truly being born again, really becoming a twice-born.

Raga and Dwesha in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

Yoga Sutras 2:7. That attraction, which accompanies [results from] pleasure [sukha], is raga.

Yoga Sutras 2:8. That repulsion which accompanies pain [dukha] is dwesha.

This is the experience of us all, but as Patanjali has pointed out, through ignorance we get sukha and dukha mixed up and our reactions are the opposite of what they should be.

To help us get untangled, a good rule is this: We cannot become addicted to what is good for us, only to what is bad for us. We see this in the way people become addicted to alcohol and drugs (including nicotine) that repelled and made them sick the first time they tried them. The body was warning them away, but after some continued use the same body began to demand and “need” them. The body being only an instrument of the mind, the addiction was also psychological.

In the same way unnatural things and behavior become “natural” to us and we blame those who do not see it the same way as we do. In fact, many addicts become very unsettled and even hostile toward those who are not addicted like them, denouncing them as fools or worse. I vividly remember what it was like to be persecuted by a history teacher in high school because I did not smoke cigarettes. It had nothing to do with history, but every so often we would have a class “discussion” on how silly it was to not smoke. (Things have certainly changed!) He would always end up by saying: “In my opinion, people who don’t smoke are doing worse things.” Such is the evil of addiction.

Many people’s favorite foods are the very things that are bad for them to eat. The same is often true of the people they like or “love.” Once the mind is distorted it avoids the good and seeks out the bad, sinking into habit patterns that can bind them for lifetimes as they revel in their “free will.” As the Gita says: “The man of restraint is awake in what is night for all beings. That in which all beings are awake is night for the sage who truly sees” (2:69).

This article was taken from the following books, which are all available as a paperback or ebook at Amazon.com and other online outlets:

- The Bhagavad Gita for Awakening, a commentary on Krishna’s teachings in the Bhagavad Gita

- Yoga: Science of the Absolute, a commentary on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

- The Dhammapada for Awakening, a commentary on Buddha’s teaching from the Dhammapada