New Study Confirms Millionaire Tax Flight Exists, Is Small

Also, Cool New IRS DATA!

UPDATE: It turns out the authors had a working copy of this paper up a loooong time ago, and I didn’t notice it. Which sort of makes me a jerk for not commenting during the comment period, then commenting afterwards. Mea culpa, and my sincere apologies to the authors. I guess among those insufficient rigorous reviewers, I should list myself.

On the heels of my recent post about “Millionaire Migration,” a new study is out in the American Sociological Review about tax-motivated migration among millionaires. This is a fascinating study because it uses the complete panel of all tax returns from the IRS from 1999–2011 that filed at least 1 year of over $1 million in income, for all 13 years. That’s amazing. That’s the kind of panel study we need if we’re going to really see how migration impacts income. Aside from using innovative new data, the study also broadly confirms the existing academic consensus: tax-motivated migration does exist, but depends on a variety of factors, and is not extremely large.

Good data and a consensus finding. This is a good study! Yay!

Now let me nitpick. This study has serious problems in the data, method, and especially interpretation. Let’s start with the data.

IRS Data Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means

Let Me Count The Ways

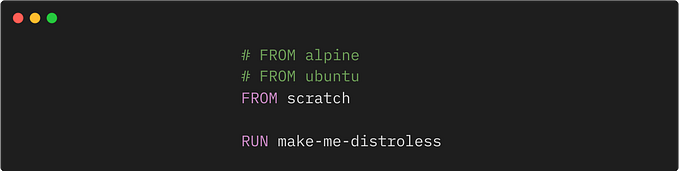

I’ve written a lot about how to use IRS migration data. Here I am with a piece published by an outside group on common mis-uses. Here I am reviewing new improvements to the data. Here I am on other new improvements. And here I am offering a visual guide to some oddities in the data. I know this data well. And it should be noted: this study did avoid the most egregious misuses of the data. They appropriately used the data to refer to fixed-year AGI, not “migration of money.” But they make a key error.

IRS tracks filing-address mobility, not tax-liability-mobility.

Whoops!

It turns out, sometimes your filing address doesn’t match the state you’re taxed in, especially in cross-border metro areas. Especially if you have complex income structuring. Especially if you file business income, or file from a business address. Consider a person who owns a law firm. Maybe they file the firm’s taxes and their personal taxes together, but file from the law firm’s address rather than their home address. If the law firm is on one side of a state line and the residence on the other, then which state’s taxes the resident will pay on his or her income depends on the existence

This doesn’t matter that much with simple wage earners. But with millionaires claiming complex income structures? Oh yeah, this matters. You need to know in which state taxes were paid. The IRS does have that data, because you claim credit for state taxes paid. But it is not tied to the migration data.

Because IRS-tracked millionaires are uniquely likely to have mis-attributed migratory status, we are likely to miss a large amount of intra-metro migratory tax arbitration.

Studies that control for reciprocity agreements (this study did not, but this other study does) reliably find meaningful tax effects. Predictably, lacking controls for these effects, this study fails to find an intra-metro effect. No surprise, but also not meaningful.

High earners are wrongly-tracked in 2011 and earlier

This study claims to offer a “census” of high-earner migrants. Sadly, it is not so.

Before 2011, the method used to track assign migratory status was deeply flawed, leading to many high earners especially being wrongly categorized as non-movers. Want proof? Here’s a paper from the IRS showing that the new (current) methodology significantly increases estimates of millionaire migration. The old method missed about 15–20% of migrants with over $1 million.

Now it is possible they are re-applying the new method to the old data. So I’m not 100% sure they are wrong here, but my basic assumption is they’re using the old data as it was categorized then. Missing 20% of migrants, and specifically 20% of migrants with the most variable and complex tax returns that may represent tax-shielding, means that this isn’t an Census. It’s a sample. A large sample, but its very size raises a concern. It’s not an 80% random sample. It seems plausible that, because we know the erroneously assigned returns were structurally different from the mover-assigned returns, that they may also exhibit different migratory patterns.

Again, this doesn’t cripple the study. It just means, you know, don’t get cocky.

Most of these millionaires are not millionaires

Only 38% of the sample was a millionaire in 8 ore more years. But anyone who was a millionaire in any year is treated as a millionaire migrant. They did not look and see, “Within this time frame, does each potential millionaire’s probability of migrating change before/after a tax increase is announced?” That’s the central question they try to answer, but it’s not the one they actually answer.

Say you’re in Florida and you win the lottery. No income tax! Great! You never need to work again!

So you quit your job. Money is no object. You have no “income” that needs to be taxed perhaps, or fairly little. You can move anywhere. Maybe you prefer to move to a high-tax, high-service area, because you already realized your income in a low-tax district.

I have no idea how common migration into high-tax areas may follow after large realizations in no-tax districts. And this study could have answered that question. But they chose not to. Probably not intentionally. But it’s telling, because this sample isn’t really showing us how actual millionaires behave, but how “people who happen to get over $1 million in a single year at some point in 13 years” behave. Some may just be retirees realizing some investments in a lumpy way!

And when we restrict to actual millionaires, i.e. those who had over $1 million in 8+ years, it turns out that a 10% change in the tax difference creates a 1.2% change in migration flows. So, for example, if the difference in taxes between Virginia and Maryland rose from 1% to 2%, that’s a 100% increase in tax differences, meaning outflows from the higher-tax state should increase by 12%.

Persistent millionaires show large responses to small tax increases.

Why do I say large? Simple: a 12% increase in flows from MD to VA would also be accompanied by a 12% decrease in flows from VA to MD, making a net change in the cross-migration balance of 24%. The vast majority of states have cross-migration balances (aka “replacement ratios”) of between 75% and 125%, while tax increase proposals of 1% of income or more are fairly common. As such, commonly advocated millionaire tax increases can lead to very significant losses of persistent millionaires. That is the simple mathematical conclusion of this study.

But again, persistent millionaires are just somewhere between 30% and 60% of millionaires, and the tax effects identified are way smaller, in some cases insignificant, for other millionaires and the general population.

Other Unique Results and Method Questions

Businesses, Investment Income, Prices, and Amenities

Aside from issues with the data itself, the study produced some unique results that may indicate method problems. I mentioned the odd intra-metro results above that probably reflect a methodological shortcoming.

Business and Investment Income

But there’s more. This study contradicts even previous studies showing small or no millionaire migration. Whereas previous studies have shown that people with large investment income are more mobile, this study shows them as less mobile. Apparently millionaires with wages are more likely to move than those with little wage income.

That finding is the exact opposite of the hypothesis the authors claim to be confirming. If you think millionaires are locally embedded, then you’d expect those with large wage income to be less likely to move, as previous studies have found.

Plus, as I mentioned, it’s likely that this method miscategorizes the residence of business-owners in many cases. So it’s no surprise business-owners are less likely to move: I wager if we compare the residential address to where the business’ taxes were filed, we’ll find a large correlation, and if we visit those places, we’ll often find that it’s actually not a house where anyone lives.

Prices and Amenities

Finally, the most obviously incorrect finding of the whole study: people prefer high prices and low incomes. This is just so silly that I can’t believe the paper let these results get published. Controlling for other factors, this study finds that millionaires significantly prefer high priced areas. Meanwhile, less significantly, everyone seems to prefer high priced areas, and low income areas. These results expose a serious methodological flaw.

If you want to give me an economic theory explaining why, even after controlling for other factors, people prefer to live in areas with high prices but low incomes, then, hey, you go, guy.

The core problem here is the lack of sufficient amenity measures. The study’s only measure of amenities in a state is the temperature (ugh). They have no measure of school quality, of pollution or crime, of government services, all variables that most studies of this topic use, because it’s super important.

What this study is really showing is that millionaires prefer low crime areas.

And to be clear, this should bother those who believe taxes don’t impact migration. Because this study is claiming that government spending has no role in appealing to migrants. In other words, those investments in roads, schools, health, public services… don’t matter. Raise taxes, and (some) millionaires will leave, no matter your spending. That’s the claim this study is making, and that claim is probably not true.

Local Taxes

There are other questions to be asked. It appears that local income tax rates were not used. That seems like a major oversight, especially in states like Maryland, Kentucky, or New York City, where these local income taxes take a big bite out of peoples’ paychecks. In other words, the core independent variable very well might be mis-measured. Now I’m not 100% sure these taxes were excluded, but they definitely aren’t mentioned, and I don’t think the TAXSIM model includes them.

And that’s an egregious oversight. If your bedrock variable is flat-out-wrong, especially for millionaire-abundant states like New York, well then, your results are biased. This is especially true given that these local income taxes would have the uniform effect of increasing the size of disparities. So um, yeah, skipping over a $29 billion tax, as of 2013, does seem like a mistake.

Likewise, they appear to have an error in the sales tax too. (UPDATE: Actually maybe not. They call it state sales taxes, but the variable seems like it may actually include local. I include my original critique here in order to show that I admit it when I’m wrong and don’t bury the evidence. The timing question still applies, however.) They cite the Tax Foundation as of 2013 giving 2011 rates — it’s not clear if they apply the same rates to every year, or if they reflect changes in each year. If they’re applying to all back years, then that’s an obvious error. But more importantly, they appear to exclude local sales taxes.

To be clear, local sales taxes raised over $100 billion in 2013. If you skip that line item, that’s kind of an egregious mix-up. It could also explain some curiosities, since New York has an extremely high local rate despite a low state rate. When you add the local rate, state sales jump from 38th ranked to 9th ranked. Oklahoma goes from 36th to 6th. These kinds of huge changes in relative tax levels could substantially alter results.

All of these questions should have been asked and answered during peer review.

The fact that it’s not even clear from the text what method was used in some cases suggests that the reviewers fell down on the job, not that the authors did something wrong or bad. I want to emphasize that point. The authors, I think, aren’t to blame for many of these problems: presumably they submitted to peer review, hoping it would get a thorough review. Unfortunately academics in the field of sociology are not known for being shy about their political leanings, and this paper appears to have gotten less rigorous scrutiny than it may have gotten in, say, an economics or tax policy journal.

Answering Interesting Questions

There Are Better Uses of the Data

The authors are pre-occupied with a sociological question about whether millionaires are predisposed to be flighty, or predisposed to be “embedded” in local areas. They conclude that the answer is “embedded,” that that model of immobile millionaires is The Model We Should Use. They explicitly reference political advocacy efforts on both sides, and are evidently responding to that advocacy.

But their own data contradicts them. Some millionaires are “embedded”. Some aren’t. Policymakers shouldn’t be taught to replace one silly model with another silly model. They should be taught to stop using silly models.

The key point here is not that this study is bad. It’s not. It’s quite good. Its broad findings line up with the vast majority of other studies. Its method was innovative, and the data it build will hopefully be used by other researchers to test other theories.

And the most interesting set of studies won’t be about taxes at all, but about economic mobility. A panel of IRS income data opens up all new possibilities with regards to migration. It should be used to answer the pressing questions about whether geographic mobility is connected to economic mobility, and exactly how.

I look forward to these authors continuing to do follow-ups on this study, and I hope other researchers get access to the data.

Check out my Podcast about the history of American migration.

If you like this post and want to see more research like it, I’d love for you to share it on Twitter or Facebook. Or, just as valuable for me, you can click the recommend button at the bottom of the page. Thanks!

Follow me on Twitter to keep up with what I’m writing and reading. Follow my Medium Collection at In a State of Migration if you want updates when I write new posts. And if you’re writing about migration too, feel free to submit a post to the collection!

I’m a graduate of the George Washington University’s Elliott School with an MA in International Trade and Investment Policy, and an economist at USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service. I like to learn about migration, the cotton industry, airplanes, trade policy, space, Africa, and faith. I’m married to a kickass Kentucky woman named Ruth.

My posts are not endorsed by and do not in any way represent the opinions of the United States government or any branch, department, agency, or division of it. My writing represents exclusively my own opinions. I did not receive any financial support or remuneration from any party for this research. More’s the pity.