“Blade Runner 2049” is Failing at the Box Office because it Fails the Cinematic Voight-Kampff Test.

Don’t let the critics fool you, “Blade Runner 2049” isn’t inexplicably failing, it’s failing because it breaks one of the most basic film making principles, it fails to create emotion — it fails Voight-Kampff.

Don’t worry about the spoilers. If you haven’t seen this film yet, you’re not going to, not at the cinema, not on pay per view, not even on late night cable. This film was DOA and no amount of defibrillating will revive it.

There’s room in the world for dark comedies, romantic slasher flics and quirky art films, but not much. Budgets for offbeat films that appeal to limited audiences have to be small. If you’re going to spend $300 million on a film you’ve got to appeal to everyone, to basic human emotions.

The folks who made “Blade Runner 2049” forgot this. The film can’t appeal to our emotions because it has no human component — because it’s not about humans.

Forgotten Voight-Kampff?

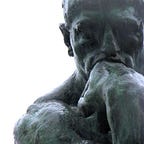

Voight-Kampff was the psychological test Harrison Ford used in 1982’s “Blade Runner” to differentiate between humans and androids. The test measured the eye’s responses as the subject listened to emotionally leading questions.

Human’s eyes responded to emotionally laden language, but replicant’s eyes didn’t, because we humans are burdened with emotions that eluded the replicants, the otherwise all but human androids in that story.

They may not have shared all our emotions, but they weren’t emotionless. Rachael’s response when she failed her Voight-Kampff test was to fall in love with Deckard, her tester. Leon’s response, when he failed his Voight-Kampff test was to kill his tester.

There were no boring androids in “Blade Runner”.

Replicants were nothing if not interesting. “Blade Runner’s” androids weren’t devoid of emotion, they felt different emotions differently, and dealt with them differently than we humans.

And therein lies the difference between “Blade Runner” and “Blade Runner 2049” — the androids.

“Blade Runner 2049” is full of androids. Almost all the characters we meet are androids, almost all the important characters are androids, but not the androids we know from “Blade Runner”. The latest versions of replicants, all but human androids, have no free will — and no emotions.

If androids had flavors, these would be vanilla, straight vanilla.

And therein lies the film’s failure. There’s nothing to fear in these androids, and nothing to like. We don’t care about them. We can’t. There’s nothing inside them about which we can care. They aren’t anthropomorphized robots, they’re disanthropomorphized humans.

And the few humans in the film are so flawed we don’t care about them either. After 168 minutes of watching androids killing androids, with the odd human thrown in, we realize our mistake — we went to the wrong movie; we went to see a film about people; this one’s about androids, emotionless, expressionless androids — boring —

— people, minus the interesting parts.

“Blade Runner” made us worry for 2 hours (and 35 years) about whether Deckard might have been an android. We worried because we cared, we liked him. We wanted him to be human. We didn’t want him to be a replicant.

And it seemed a real possibility, since the androids in his world not only had free will, they had something more important and interesting — personalities.

The androids in “Blade Runner” weren’t just as interesting as humans, they were far more interesting than most humans. We had no idea, when an android was on the screen what would come next, a kiss or a broken neck.

Joanna Cassidy, Brion James, Daryl Hannah, Sean Young and Rutger Hauer are burned in our cultural memories as the characters they played in this film.

In “Blade Runner 2049” however, there are no anxieties, no worries — and no mysteries.

We know in the first few minutes K, our protagonist, is an android, and though he’s violent, his violence is emotionless. We were used to beautiful, complicated, alternately charming and explosively dangerous, bigger than life androids.

K is the Casper Milquetoast of androids. He’s a an emotional zero. He eats, sleeps and fights wearing the same expressionless mask and using the same expressionless voice throughout the entire film.

No matter how daunting are his trials and tribulations, we find ourselves as unable to care for or about him as he is unable to care for or about himself. His life or death mean nothing, because they’re not his.

He’s not the only character who leaves us cold. His human boss, Robin Wright’s combed back, greasy cop look and lonesome loser (at one point she seems to proposition K…who doesn’t respond) persona make her even less appealing than her emotionless android employee. She seems unmoved by anything around her but tracking down rogue, older model androids. She’s so jaded she can’t even bring herself to care about her own murder, and surprise — neither can we. We barely flinch as she dies.

Even our villain, if there is one, fails in his role. We can’t bring ourselves to like him because he’s not likable, neither can we hate him. Jared Leto inspires more pity (he’s blind) and disbelief (he grows countless perfectly functional human bodies, but can’t grow himself a new set of eyes? You bet…) than fear.

Instead of a bigger than life, completely unstoppable, unspeakably evil villain, he’s a pathetic, powerless, helpless figure. He can’t walk across a room without assistance, or even see his own creations without gimmicky electronic aids, and his glazed eyes leave him even more expressionless than his emotionless android assistant, Luv…

…who kills almost everyone and everything that crosses her path…in between having her nails done. She’s not likable, but not hatable either; because she’s just an android, without free will, doing her job, like a wrench or a hammer in the hands of a deluded blind man.

We care little about the beings she kills, and even less when she herself eventually dies, because she wasn’t human, she was never emotionally alive.

We’re almost 2 hours into the film before we encounter a human capable of expressing emotion, Rick Deckard. Unfortunately, the emotions he expresses are, for the most part, the “get off my lawn” type.

In one of the film’s supreme disappointments, after 35 years of wondering what happened to him, in “2049” we find out — the sympathetic hero of “Blade Runner” has turned into a grumpy old man, living on his own in an abandoned casino, drinking a lifetime supply of whatever’s behind the bar.

And, when he fails to fight off the androids or rescue himself from a sinking car he becomes a passive hero, i.e. a non-hero, and we begin to wonder why, after all these years, we cared or still care what happened or will happen to him, or even his hapless daughter, unfortunately and unwisely confined inside a glass dome that precludes her from interacting with anyone outside.

The only appealing character thrown our way isn’t human, or even an android, it’s an AI named Joi, sweetly played by Ana de Armas, and displayed visually as an untouchable and untouching hologram.

Yes, the only appealing character in the entire film is a mass produced, big box store, cellophane wrapped, bundle of photons. And even though she’s sweet and sensitive, when she’s eventually deleted we’re unable to grieve because, after all, she’s only a collection of 1s and 0s on a thumb drive.

Sure, she’s digitally dead, but anything that’s digital can be rebooted, reborn. K could always buy another thumb drive and program another Joi to be sweet and sensitive again, or not, maybe he’d rather have a schizo bitch for a companion next time around.

The film is replete with passive, boring, unlikable heroes, passive, boring, unhatable villains, boring supporting characters, ridiculous plot devices, an all exclusive emphasis on design, and an overwhelming infatuation with CGI.

We spend far too much time looking at sets and digital effects that add nothing to the narrative, and eventually become as tedious as each character’s habit of speaking s l o w l y and e nun ci a ting per fect ly, as though they’re pronouncing great truths being recorded for posterity.

This film won’t make it to posterity. There is no market for 2 hours and 48 minutes of boredom. If there were, C-SPAN would be a hit.

Art design and CGI help films, but they don’t make them; characters and stories make films.

We don’t go to the multiplex to see pretty pictures. We go to cheer underdogs, to fear for the weak, to hate the villains and to worship the heroes. We go to care. “Blade Runner 2049” gives us no one to cheer, no one for whom we fear, no one we hate and no one to worship. It gives us no reason to care. It leaves us emotionless.

Our eyes are unmoved.

And in that, it fails the film maker’s Voight-Kampff test.

It’s time for Alcorn, Sony, Denis Villeneuve, Michael Green and all 16 of the film’s producers to go back for a “Story” refresher because this film should never have seen the light of day. It failed basic storytelling principles.

It’s hard to believe no one stood up in an early development meeting and asked: “Who’s our hero? Why do we like him? Who’s our villain? Why do we fear or hate him? Is the ending happy or sad? If we don’t have a hero to like or villain to hate and we can’t figure out whether the ending is happy or sad, is this really a cinematic story? Will anyone care? Will anyone buy a ticket?”

We don’t care, and as the box office shows, we’re not buying tickets.

The only question the movie will raise in any viewer’s mind is how a score of film professionals could greenlight a $300 million investment and make a film doomed to fail the instant the digital ink dried on the electronic page.