Unseen PhD Effort, “Failures,” and the Research Iceberg Analogy

When one does a PhD — or any research for that matter — there is an enormous amount of unseen effort. The enormity of the unseen effort can be discouraging, especially while in the middle of a project. This unseen effort can include countless hours of thinking, research instrument development, experimentation, “failures,” and more.

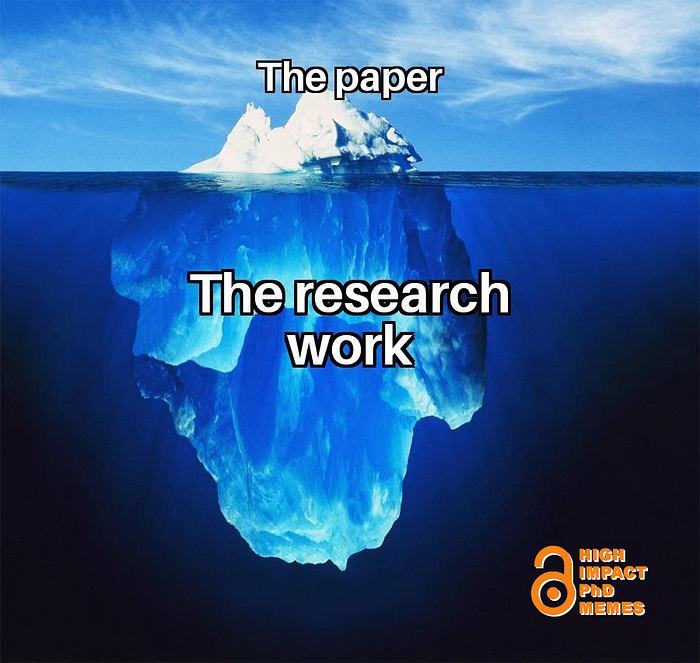

Below, I offer some perspectives on this unseen effort. In doing so, I reference the “Research Iceberg Analogy:” the notion that much of a research project (like much of an iceberg) is invisible (below the surface of the water).

I include my variant of the “Research Iceberg Analogy” figure below.

Overview of my version of the “Research Iceberg Analogy” diagram.

Paraphrasing from my earlier post on PhD Bubble Diagrams, the research process (generally) consists of (1) identifying potential projects, (2) selecting which problems to work on, (3) working on those problems, (4) refining the work for publication, and (5) dealing with setbacks along the way. Eventually, one enters the phase of (6) publishing the results.

The cyclical pattern in the above diagram indicates the repetitive cycle of (1)-(2)-(3)-(4)-(5)-(1)-(2)-(3)-(4)-(5)-(1)-(2)-(3)-… that happens before the work is finally published (6). The mass of the cycles below the water surface represents the significant amount of effort that goes into a research project but that is not visible in the resulting publication.

Personal examples.

I wrote a sidebar with personal examples of the iterative research process. Since Medium doesn’t support sidebars (to the best of my knowledge), I put the sidebar in a separate (short) post.

On projects and dissertations before publication: Below the surface of the iceberg.

When in the middle of working on a project or a dissertation, one is constructing the base of the iceberg. This process is time-consuming and can be discouraging!

One might conduct and then throw away the results of numerous preliminary experiments as they work toward identifying the final experiments to include in a paper. One might build a research instrument or write some code that they end up not using. One might change their underlying research questions or research objectives. In short, one might restart the research cycle multiple times.

During this phase, one doesn’t completely know what the visible portion of their iceberg will look like. One might not even know if they’ll ever have a visible portion of the iceberg. Naturally, this can be a very challenging time for researchers.

On projects and dissertations after publication: Looking at icebergs from above the surface.

The feeling of pride and joy after successfully publishing a research project is beyond compare. Now the tip of the iceberg is visible for the world to see! Congratulations!

In my experience, one’s perspective on their research project changes after one sees their research product enter the world. The pain and suffering during the research process were still real— the uncertainty of whether one was headed in the right direction, the torment over “failures” (see below), and more. But, now, the iceberg is complete and can be celebrated.

I encourage researchers to reflect upon their entire research process before the memory of working on the iceberg base fades too deeply (see the following figure). For example, a researcher might ask themselves questions like:

- What lessons did I learn as I worked on this project?

- If I were to redo this project, knowing what I know now, what would I do differently? What would I do the same?

- How would I carry out future projects based on the lessons that I learned? What would I do differently? What would I do the same?

- What would I tell myself if I find myself stuck while working on a future research project?

After finishing multiple projects: A sea of icebergs.

After completing multiple research projects (after building multiple icebergs), one’s perspective on the research process changes. When engaged in one’s first research project (one’s first iceberg), there are many unknowns. For example, a common question I often hear is, “Am I am approaching this problem in the right way?” Or, “Is it valuable to spend my time working on X when I’m not sure if X will be included in my eventual publication?”

It is okay to have these questions!

It is okay to not to know the answers to these questions!

After completing multiple projects, a researcher begins to develop an intuition for how to answer these types of questions while still in the middle of a project. As a result, the process of building future icebergs becomes less daunting. It is at this stage that one’s research activities often explode.

A note to mentors: mentors have successfully completed multiple projects and, as a result, their perspectives on the challenges with building an iceberg are different than the perspectives of a junior researcher engaged in the middle of building their first iceberg. It is important to keep this different perspective in mind.

On how to interpret “failures” while forming the base of the iceberg.

When forming the base of the iceberg, we often repeat the research cycle: (1)-(2)-(3)-(4)-(5)-(1)-(2)-(3)-(4)-(5)-(1)-(2)-(3)….

I frequently hear the term “failure” to describe a situation in which a researcher realizes that one direction isn’t working out and they have to step back and try a different direction.

I strongly dislike the word “failure” here. In my mind, the realization that one direction isn’t working out and that one should try a new direction is a success! The researcher has learned something and has developed better insights into the next direction to take the research. Also, research is about exploring unknowns, so — almost by the definition of “research” — one should expect to experience “failure” along the way.

One way to think about “failures:” as you explore multiple directions, you are creating a massive, solid base for your research iceberg. The more solid your research iceberg base, the easier it will be to create a visible (published) tip.

Also, when a research project experiences (so-called) “failures,” the researchers grow as researchers. I reference again my earlier PhD Bubble Diagrams post:

My philosophy is that the addition of new knowledge is a byproduct of the PhD process. To me, the most important part of a PhD is experiencing the PhD process — learning how to….

If one is in the middle of a research project and realizes that they need to shift directions and return to an earlier phase in the research cycle, then they will be better equipped to handle future “failures” and guide others (possibly their own students, years later) through “failures.” They will also have a greater intuition for how to avoid similar “failures” in the future. This is all growth in a positive direction!

Thus, I highly encourage researchers to not consider shifts in direction or negative results as “failures,” but as successes (A) along the path of advancing the project and (B) along the path of growing as researchers.

Also on the Research Iceberg Analogy.

I wrote two additional posts on the Research Iceberg Analogy:

- On Comparing with Others and the Research Iceberg Analogy

- The Art of Research Paper Writing and the Research Iceberg Analogy

Alternate images.

These are two other images that I’ve seen and that I think are also valuable. I like the beauty and simplicity of the following image:

I like how the following image surfaces the unseen characteristics of the researcher that made the visible research possible:

Acknowledgements.

I learned so much about the PhD process from my own advisor, Mihir Bellare. After obtaining a faculty position, I continued to develop my own philosophy on advising and the PhD process through the advising my own PhD students. Much of my thoughts on advising and the PhD process have also been shaped through the co-advising PhD students with UW Security Lab co-director Franziska Roesner. Thank you to all the students and postdocs that I have advised, past and present! Thank you also to Kaiming Cheng, Camille Cobb, Ivan Evtimov, Earlence Fernandes, Umar Iqbal, Lucy Simko, and Eric Zeng for comments on my writings about icebergs.