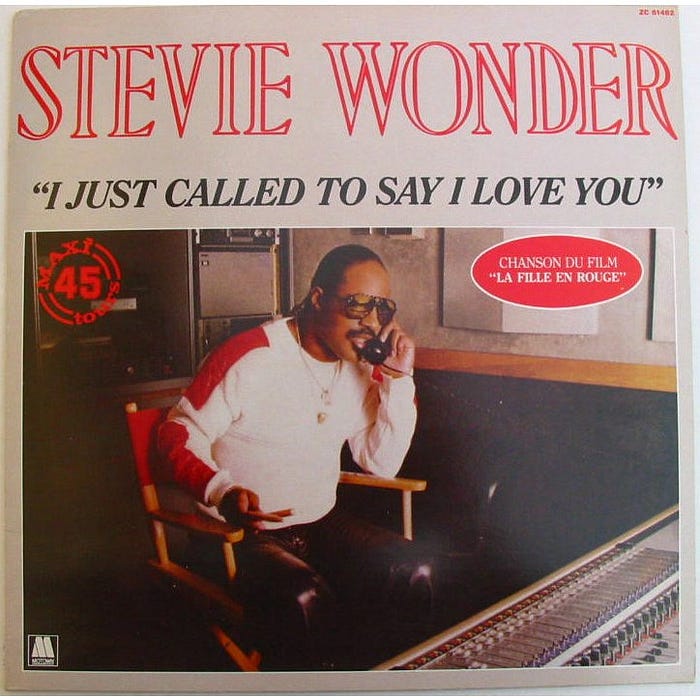

‘I Just Called to Say I Love You’

“I Just Called to Say I Love You” is ingeniously simple: It doesn’t matter what day it is, I love you all the time.

Every day, I’ll write about a random song. Maybe it has had an impact on me. Maybe not. Either way, these are songs that have helped shape me.

On Oct. 13, 1984, “I Just Called to Say I Love You” reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. Six days later, I was born.

There’s nothing particularly great about “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” the lead single from “The Woman in Red” soundtrack, which is practically a Stevie Wonder album by itself, though clearly the genius filled the collection up with some scraps. To be real, “I Just Called to Say I Love You” is a scrap, but in the way that Paul McCartney’s “My Love” was a scrap. Deep inside, Wonder knew the song wasn’t that great, but he was aiming for the charts. This was a soundtrack. There was no political message in the groove, no heady rumination to study. This was a soundtrack, and the lead single needed to do something on the charts. So the lyrics are, at best, banal:

No New Year’s Day to celebrate

No chocolate-covered candy hearts to give away

No first of spring, no song to sing

In fact, here’s just another ordinary day

It’s the calendar, month to month and moment to moment, and the song’s message is as simple as Wonder gets: It doesn’t matter what day it is, I love you all the time.

I just called to say “I love you,”

I just called to say how much I care

I just called to say “I love you,”

And I mean it from the bottom of my heart

This isn’t “Living For the City.” It’s not even “Signed, Sealed, Delivered.” Naturally it stayed at №1 for three weeks. This is a consumption anthem of the highest order, the kind of song everyone can get behind because every single person can relate to some day on the calendar. And you know, there’s special genius in understanding that and crafting that obvious knowledge into a compact pop song, which is why Wonder is so incredible (also, we shouldn’t forget, his near-peerless musicianship and, oh, he’s blind).

So this song was №1 when I was born, and in the first week or so after returning from the hospital. I didn’t hear the song until the Huxtable family jammed out with Wonder’s synclavia on “A Touch of Wonder,” the season-two episode — which I caught in rerun — that neatly encapsulates everything great about “The Cosby Show” while shoehorning a major celebrity appearance. We get disgraced human being Bill doing his “baby” shtick, Claire purring about and acting surprised that she could be so damn cool, and of course, Theo’s legendary only-in-the-’80s phrase “jammin’ on the one.”

Members of the culture intelligentsia have written eloquently about that episode, but all this lower-middle-class urban white kid remembers is that it was fun. It just seemed so damn fun to be in Stevie Wonder’s studio, laying down beats and making up farm animal noises.

Thus, all my memories of “I Just Called to Say I Love You” are happy. And I think most memories of this song are happy for most people. Folks who raise their noses at Starship and Huey Lewis have trouble faulting this song, because even though the words are elementary and the melody is simple, Wonder’s high-reaching joy keeps this song happily floating near the sun. And when the Huxtable kids sing the №1 hit with Mr. Wonder, it’s undeniable.

And then there’s the sentiment.

“I Just Called to Say I Love You,” again, is ingeniously simple: It doesn’t matter what day it is, I love you all the time. And, to extend that, I will call you just to say that I love you.

I don’t do this much, if at all. I call someone to tell him or her that I need something, or maybe to catch up on life, but it’s a unique occurrence that I call someone to say “I love you.”

Maybe upbringing is responsible for some of this, that the lack of outward love shown to me through my life — and, instead, a combination of tough love and small, everyday action — shaped me to deny giving real, public and outward love. I felt the most love during holidays and birthdays, major marks on the calendar that came laced with anticipation. And because of that anticipation, even days with the most love felt crushingly disappointing. Maybe I was awaiting something besides being playfully — or not playfully — teased by everyone for being soft, or feminine. Maybe I just wanted a real hug.

My wife Sarah is a real hugger. She touches and kisses, too, which means some may describe her as “overly affectionate.” I said as much, at times feeling threatened by it, at times feeling disgusted by it. I wouldn’t hug, touch or kiss in return, or I would quickly pull away or act too busy or too annoyed. Sarah’s display of outward love unnerved me, but most of all, scared me, and all because I wasn’t used to it, I hadn’t lived with it, and I couldn’t understand it. In short, it was foreign.

As a child I was sensitive. I responded to verbal blows by classmates, school bullies, neighborhood tough guys and family members by whining and weeping to whomever who could help me. But my tears were considered the wrong reaction. “Stop being so sensitive,” I’d be told. It didn’t matter. I cried a lot as a kid. I cried to adults. I cried to peers. I cried to myself, and more than anyone knows, typically in my bedroom alone at night, and listening to Vanessa Williams’ “Save the Best for Last” or Janet Jackson’s “Again.”

Twenty years after “Again,” Sarah was touching, hugging and kissing me, and in my head I was repeating the same thing I was told as a kid: “Stop being so sensitive.” Arguments ensued. Slowly the voice in my head would overcome me, and I would break down, wondering why I couldn’t open up and simply give and receive love outwardly. I could cook dinner every night. I could hold the door open. I could write infrequent emails that expressed my deepest feelings. But I couldn’t give a real hug. I couldn’t just call to say “I love you.”

“I Just Called to Say I Love You” became one of the songs Sarah and I sang together, first because she doesn’t remember the lyrics to pop songs, but this one was easy enough; second because it came on enough during long car rides; and third because, as I explained to her, it was the song that was №1 on the Billboard Hot 100 when I was born. I’ve always remembered that, always wanted to tell people that, and for what reason, really? To recall “Jammin’ on the one”?

When we sing together, something clicks. She can sing. I really can’t. But it doesn’t matter. We’re a team, deeply in love, deeply having fun in the moment, much in the same way the Huxtable kids were having fun in Wonder’s studio, much in the way I had fun watching “A Touch of Wonder.” My cares drift away. Being sensitive or not being sensitive doesn’t matter. For four minutes, I can sing the song away with my wife and focus only on getting the words right and have a blast doing it.

In a weird way, singing along with “I Just Called to Say I Love You” is my way of calling Sarah just to say I love her.

It’s the sentiment I couldn’t ever express as a child, the one denied to me for decades, the one that built walls in my adulthood — walls that I’ve had to scale repeatedly, and walls that, to this day, I continue to scale. I still have trouble returning Sarah’s hugs, touches and kisses. I still can turn annoyed. But now I’m aware of the feeling, and just as important, I know that there’s a song out there — one I can find on any random day — to remind me that I am capable of all kinds of love.