Final Paper

Putting the Life Back in Death

“Now, there really isn’t anything radically wrong with being sick or with dying. Who said you’re supposed to survive? Who gave you the idea?[1]”

-Alan Watts

INTRODUCTION

In an article published by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) News, Canada is the latest country to join a growing trend, like the one experienced across Europe, to host a gathering of people in a casual setting who talk about a taboo subject, namely death. In Halifax, Nova Scotia Deborah Luscombe started an open forum in a downtown Halifax café which encourages people in the local community to get involved and talk about the one thing that most human beings in Europe and North America dread talking about. Luscombe comments that “My goal is to encourage the conversation around death to come out of the closet. It’s an event we all share, inevitably. I think there’s fear. It’s just been a taboo subject[2]”. A former mid-wife and a devoted Buddhist practitioner, Luscombe believes that it is only through embracing death does one ever find the meaning of life. It is this point that many Buddhist traditions have been trying to emphasize over the centuries to lay people around the world. Death is not something to hide in the closet and hope it stays there; it is something to bring out in the open and worn everyday just as one goes through life wearing clothes each day, hopefully. Many cultures in places like Thailand, Japan, China, and Sri Lanka already understand this view from a Buddhist perspective. With the growing interest in this subject matter now spreading to North America, the significance of this case needs to be discussed to enlighten individuals still oblivious to this trend.

As such, in this paper I will discuss the subject of death from the perspective of Tibetan Buddhism. First, I will give a brief historical account and general practices regarding death in Buddhism as practiced in the region of Tibet. Second, I will discuss how these practices can enlighten and enrich the social welfare of contemporary human beings living in the Western world as part of a technologically advanced and modern society. Finally, I will conclude with a brief overview of the themes discussed and suggested further research questions. It should be noted that this paper is not meant to an exhaustive account or meant to cover all traditions in Buddhism regarding death. Instead, the idea is to guide the reader through some introductory material regarding the view of death in Buddhism, as practiced in Tibet, and to see how this material is applicable in modern society.

TIBETAN HISTORY AND PRACTICES ON DEATH

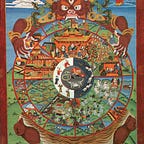

In order to give a brief historical account and general practices regarding death from the Buddhist perspective, it is prudent to begin with a document that deals specifically with this subject matter. Buddhist death practices vary throughout the world but the most rich and long standing tradition on this matter comes from the tradition that is practiced in Tibet. The mortuary document that is widely used in this region is the Bardo Thodol or more commonly known as the Tibetan Book of the Dead. According to folklore, during the eighteenth century the guru or spiritual teacher Padma-Sambhava brought this work to the region of Tibet but concealed it due to his belief that the people of the time were unable to comprehend its message and meaning. Therefore, he hid this document in various places like underneath stones, in lakes, and as part of ancient pillars. Overtime this document was collected and put together to create what is today known as the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Although Western readers remained largely in the dark to these teachings until in 1927 Dr. Evan-Wentz along with the Lama or teacher Kazi Dawa-Samdup set out to create what remains to be one of the most ambitious works in academic and scholarly history[3]. The title the “Tibetan Book of the Dead” was extracted from the work the “Egyptian Book of the Dead”, which had already been translated and published in the West, in order to signify the similarity of the subject matter. A closer translation of the original work would render the title to be “the after-death experiences on the bardo plane or intermediate state”. A noteworthy point is to highlight how both the Egyptian and the Tibetan Book of the Dead deal with similar subject matters and take the after-death state as being something which is factual even though they were authored centuries apart from their inception. This signifies a cultural similarity between two separate peoples living centuries apart pointing to a common theme of the human condition.

The Bardo Thodol is essentially a mortuary document which is meant to be recited over a deceased person’s body over the course of forty nine days. The reading is meant to help guide the deceased through the experiences of the intermediate state between death and rebirth. In the very rare cases this is not necessary because the deceased has gained liberation or nirvana and therefore escaped the cycle of birth and death. The readings themselves can be broken up into four sections. First, the moments of death are described where physiological changes in the body are discussed and the censoring of the environment around the dying person. The censored environment, that is the absence of any loved ones or cherished possessions, is meant to remove the feeling of attachment the individual may have that would cause her to regret the process of death. This is characteristic of Buddhist practices throughout the world, that is, the perfecting of non-attachment. Second, a reading to the deceased of the dawning of the peaceful and wrathful deities is recited for guidance in the intermediate state and a constant reminder is reiterated for the deceased to recognize the fantastical illusions that she experiences as nothing more than the workings of her own mind. Third, the after-death state is described in detail to help guide the deceased’s thought process to a higher level of rebirth. Finally, once rebirth is guaranteed for the consciousness principle the process of rebirth itself is described in detail. The major influences that helped to create the fantastical stories and imagery in the Bardo Thodol can be attributed to four major schools of thought: Indo-Buddhist doctrines derived from philosophical and esoteric traditions, the early Tibetan notion of the bardo derived from the Abhidharma or scholastic works of Indian origin, the relationship between human beings and pretas or hungry ghosts folklore, and the influential documents surrounding the revered and enlightened being in Asia known as Avalokitesvara[4].

This backdrop provides a brief introduction to some history and general practices exercised in Tibet regarding death and dying. It would be prudent now to turn to how these teachings can be applied in the Western world to better enrich the social welfare of individuals.

THE VIEW OF DEATH IN THE WEST

The Tibetan view of death and dying can have a positive impact for people living in the technologically advanced and modern Western world. To begin with, the most important difference between people in the West and people living in Tibet is the attitude centered on death and dying. For the most part, people in the West view death as being a catastrophic end to the party of life. With the scientific revolution and the enlightenment age along with the “death of god”, as Friedrich Nietzsche put it, the idea of an after-life was pretty much extinguished from the Western soul exacerbating the idea that this life is all one would ever know. Now, I’m not here trying to make a case for the after-life but simply trying to show how a shift in the attitude from thinking that this life is all there is to this life is all one needs may greatly improve attitudes centered on death. On the other hand, people in Tibet view death in a different manner. For the most part people generally believe in the doctrine of rebirth and therefore an afterlife of sorts although not quite the same as the after-life portrait painted by traditional Western religions. As Geoff Childs comments: “Life begets death: that is a universal constant. Whether one believes in reincarnation, an after-life or neither, a human’s physical existence is shadowed by the inexorable march toward decay and dissolution[5]”. This is exactly the point that the modern Western soul needs to accommodate and take a hold of. Death should no longer be a grim subject but one discussed at length and examined. Ultimately it is out of attachment that the Western soul is unable to accommodate such thinking. Young Westerners grow up bombarded with cultures of consumerism and consumption and develop attachments to things which are not even essential for human survival.

Furthermore, the same young Westerners growing up in these corporately fashioned cultures run the risk of developing mental health issues and severe social disorders and anxieties. This downward cycle may be halted by a simple change in attitude on the matter of death and dying. Donald S. Lopez Jr. does an excellent job of painting this portrait by stating the following: “Although everyone knows that death will come in the end, everyone thinks with each passing day, “I will not die today, I will not die today”, mentally clinging until the moment of death to the belief that they will not die[6]”. This same attitude is what allows for the social and psychological conditions, mentioned above, to flourish. If Westerners began to develop the attitudes of death that the people in Tibet have been perfecting for centuries, then there is a strong possibility for liberation from the mental shackles that death has imposed on the Western mind.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, I have attempted to discuss the subject matter of death as practiced by Tibetan Buddhism. A brief historical account and general practices were highlighted to show where this tradition is coming from and how people living in Tibet today generally practice it. The second part of this paper highlighted the differences in attitudes that Western people and people living in Tibet have when it comes to the issues of death and dying. Attachment, a key subject of Buddhist study, was highlighted as being a determining factor in the shaping of the Western attitude surrounding death. It seems then that what Gautama Buddha taught about attachment being the root cause of suffering is true in this sense. But ultimately further research needs to be carried in order to answer questions like: Why has the attitude surrounding death in the West varied so much from attitudes in places like Tibet? What is the role of attachment in influencing the attitude towards death and dying? And how can the Tibetan attitude on death help mental health individuals and terminally ill people around the world? These are all questions for a future researcher to address and I hope that this paper has inspired such research to be carried out.

[1] YouTube. “When Death Happens-Alan Watts”, Video URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BLKb-G18K00.

[2] Jennifer Henderson, “Death Café Starts up in Halifax”, (Halifax: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation News, March 2015), Document URL: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/death-caf%C3%A9-starts-up-in-halifax-1.3013036.

[3] Translated by Kazi Dawa-Samdup, Edited by W.Y. Evans-Wentz, Forward and Afterword by Donald S. Lopez Jr., “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), Pgs. 2–3.

[4] Brain J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I. Stone, “The Buddhist Dead Practices, Discourses, Representations/Chapter 9: The Death and Return of Lady Wangzin Visions of the Afterlife in Tibetan Buddhist Popular Literature”, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007), Pgs. 300–306.

[5] Geoff Childs, “Tibetan Diary from Birth to Death Beyond in a Himalayan Valley of Nepal/Chapter 9: Parting Breaths Death is but a Transition”, (California: University of California Press, 2004), Pg. 156.

[6] Donald S. Lopez Jr., “Religions of Tibet in Practice/Chapter 28: Mindfulness of Death”, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), Pg. 427.

Bibliography

1.) Brain J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I. Stone, “The Buddhist Dead Practices, Discourses, Representations/Chapter 9: The Death and Return of Lady Wangzin Visions of the Afterlife in Tibetan Buddhist Popular Literature”, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007.

2.) Donald S. Lopez Jr., “Religions of Tibet in Practice/Chapter 28: Mindfulness of Death”, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

3.) Geoff Childs, “Tibetan Diary from Birth to Death Beyond in a Himalayan Valley of Nepal/Chapter 9: Parting Breaths Death is but a Transition”, California: University of California Press, 2004.

4.) Jennifer Henderson, “Death Café Starts up in Halifax”, (Halifax: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation News, March 2015), Document URL: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/death-caf%C3%A9-starts-up-in-halifax-1.3013036.

5.) Translated by Kazi Dawa-Samdup, Edited by W.Y. Evans-Wentz, Forward and Afterword by Donald S. Lopez Jr., “The Tibetan Book of the Dead”, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

6.) YouTube. “When Death Happens-Alan Watts”, Video URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BLKb-G18K00.