The Death of “Crazy Uncle” (Major Blog 3)

Following the days after the New Year celebrations, the local nuns and monks invited as many of the village people as they could to attend the monastery to discuss the funeral rights for the body of “Crazy Uncle”. I made my way over to the monastery on the morning of the meeting with my friend Chodak. “Crazy Uncle” was apparently, from what the nun from the monastery had told me, a tantric practitioner who barely talked to anyone and hadn’t been seen in a number of years prior to his death. No one was sure as to what he had been up to prior to his death in the cave he resided in on the outskirts of the village over the past few decades. Based on my knowledge of the process of death from a tantric perspective, five elements make up the human body and the word “death” is meant to signify the breakdown of these five elements. A key point to note among tantric practitioners is that the element of “wind” is the essential energy that animates human life. When the “wind” element is taken away, the human begins to shut down physiologically speaking[1].

I had assumed that the old man’s body would be given the right that most practitioners of Buddhism followed in the village, namely, cremation. But as Chodak and I entered the monastery, we could hear debates going on between the villagers as to what to do with the body. Chodak and I sat to one side and heard what the villagers were actually saying. Some claimed that he was a noble saint and should be afforded the funeral right of such while others claimed that he was a drunkard who spent his time drinking in his cave far removed from noble acts. No one was actually sure what kind of man he was and what sort of life he led. As I sat back and heard all the arguments against a man who was no longer able to defend himself, I thought to myself what kind of life this “Crazy Uncle” had lived? Right away I figured out that this man couldn’t have been a noble saint or a drunkard. First off, if he was a noble saint, as some of the village people claimed he was, surely his character would not be brought into question. For example, many people think of Gautama Buddha as a Tathagata or “one thus gone”. Someone who is known for wisdom and knowledge; but others may argue that he was a charismatic yoga guru who managed to infatuate the young and old alike into thinking along the same lines of thought as he did much like Socrates in ancient Athens.

I have yet to hear of any creditable account of Gautama as being a drunkard or someone of low moral and ethical stature. Similarly, if “Crazy Uncle” was a noble saint then people would argue to what degree he was “saintly” just like they do the wisdom of Gautama and not contrast his character with a totally opposite and clashing personality. On the other hand, I also figured that “Crazy Uncle” couldn’t have been a drunkard who spent his time drinking in a cave and oblivious to the world around him. Surely a person who was rumored to be a tantric practitioner couldn’t also be a common drunkard. If “Crazy Uncle” did indulge in large quantities of strong drinks then he must have been doing so out of some practitioner devotion to his interpretation of the tantric tradition. In other words, if he was a drunkard he must have thought that being in an intoxicated state brought him closer to realizing or recognizing the ultimate truth, whatever that may be according to him.

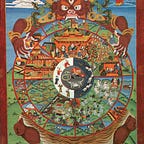

Regardless of these contrasting lifestyles, it seems it is true what a practice of the mindfulness of death teaches, that is, there is no place to stay unharmed by death. It does not exist in space, the sea, or in the midst of the mountains[2]. “Crazy Uncle” is a perfect example of this teaching. No matter how much someone might try and escape the world, death finds a person in any corner of the earth be it in a populated village or a secluded mountain side cave. Buddhism, most generally taken, teaches that the worldly life is nothing more than an illusion. One’s daily life, choice, love, hate, and craving are nothing more than a veil cast in front of the eyes to blind the individual from seeing the true nature of reality, that is, emptiness. Death in this sense is an opportunity to escape from this illusion and have a chance to see reality for what it really is. Most other cultures trend to demonize death as being a farewell party for the individual experiencing it with the consequence being that the “show” goes on after the individual passes.

Buddhism and its various sects seem to do the opposite and welcome it as a road to experiencing and knowing the truth. Now, “Crazy Uncle” must have to some extent known this and therefore wouldn’t have cared what happens to his body once his consciousness principle had passed. This is what was getting to me as I sat and listened to the villagers with my friend Chodak. The fact that all these people were arguing over what is essentially disposal of a human body, as blunt as that sounds, when Buddhism teaches that after death the body is no longer of any use to the consciousness that has escaped. What matters in Buddhism, according to a Shingon Monk named Kakukai (1142–1223), is not so much what to do after one has died but the moments before one’s death; as he notes: “I think it is quite splendid to die as did the like of (the recluse) Gochibo, abiding in a correct state of mind with his final moments unknown to any others[3]”.

With that being said, the body of a deceased person in Buddhism can be used to determine what sort of rebirth one may gain or even if one was able to obtain liberation. This is usually done by examining the body for post-mortem signs. According to traditional teachings in the village, if a deceased person’s head was warm and her feet cold, then that means that she was able to obtain liberation and escape the cycle of rebirth or gained a noble rebirth in the after death state. On the other hand, if the opposite came to fruition, that is, the head was cold and the feet were warm then that means that the consciousness principle escaped from the individual’s feet and therefore gained rebirth into a lowly existence. For these reason one’s body would tell a story after her death but wouldn’t in any case help that person. This practice is meant to be a comfort for the person’s loved ones. However, the reading of the Tibetan Book of the Dead or the Bardo Thodol over one’s body may help to guide the individual during the after-death or intermediate state between death and rebirth.

As these thoughts ran through my mind as me and Chodak sat and listened, I looked outside from the monastery at the sky and saw what appeared to be the most fantastical rainbow my eyes had ever seen. The sky was blue like the deepest sapphire stone I had ever seen and birds could be seen singing and hovering around the monastery. As if I was in a trance, I got up and made my outside to the monastery courtyard and looked on in amazement. I could feel Chodak’s eyes leering at me as I got up and left but I didn’t pay much attention to it. As I stood there in awe I felt the gentlest breeze rush through my hair and whisper in my ears. It was at that moment that I realized what kind of life “Crazy Uncle” must have lived. Similar to when Milarepa’s death approached it is said that: “The clear sky was filled with a rainbow outline of a Go board, as if one could touch it. And in the center of each square there was a variegated eight-petaled lotus, each with four petals in the cardinal directions. And upon these were three-dimensional mandalas, drawing more amazing and marvelous than any made by expert craftsmen[4]”.

After seeing the signs in the monastery I knew that what should be done to “Crazy Uncle’s” body was to be nothing short of a burial fit for an enlightened being. Realizing this I made my way back into the monastery to hopefully convince and show the villagers the signs that were right in front of them.

[1] Kurtis R. Schaeffer, Matthew T. Kapstein, and Gray Tuttle, “Sources of Tibetan Tradition: Chapter 14 Writings on Death and Dying”, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), Pg. 447.

[2] Donald S. Lopez Jr., “Religions of Tibet in Practice: Chapter 28 Mindfulness of Death”, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), Pg. 431.

[3] Jacqueline I. Stone and Walter Mariko Namba, “Death And The Afterlife In Japanese Buddhism, Chapter 2: With The Help Of “Good Friends” Death bed Rituals Practices In Early Medieval Japan”, (Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, 2008), Pg. 81.

[4] Kurtis R. Schaeffer, Edited by Bryan J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I. Stone, “The Buddhist Dead Practices, Discourses, Representations, Chapter 6: Dying Like Milarepa Death Accounts In A Tibetan Hagiographic Tradition”, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007), Pg. 213.

Bibliography

1.) Donald S. Lopez Jr., “Religions of Tibet in Practice: Chapter 28 Mindfulness of Death”, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

2.) Image URL: http://www.springbrook.com/Tibet-yak-pictures/Tibet-yak-pictures/Tibet%20Stupa%20rainbow.jpg.

3.) Jacqueline I. Stone and Walter Mariko Namba, “Death And The Afterlife In Japanese Buddhism, Chapter 2: With The Help Of “Good Friends” Death bed Rituals Practices In Early Medieval Japan”, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

4.) Kurtis R. Schaeffer, Edited by Bryan J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I. Stone, “The Buddhist Dead Practices, Discourses, Representations, Chapter 6: Dying Like Milarepa Death Accounts In A Tibetan Hagiographic Tradition”, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007.

5.) Kurtis R. Schaeffer, Matthew T. Kapstein, and Gray Tuttle, “Sources of Tibetan Tradition: Chapter 14 Writings on Death and Dying”, New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.