Why the Passive Protagonist of Vampyr Is Its Greatest Storytelling Strength

Your blood is drained and you’ve breathed your last but Vampyr is just getting started

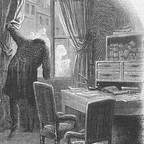

In Vampyr, a student of the occult travels to an obscure French town living under the shadow of an evil spirit. In search of answers, he passes between the worlds of the living and the dead, the light and the dark, risking his soul to vanquish the spirit and save the town.

At least, that’s how I’d describe the film. There’s a subjectivity to Vampyr, a liminal space that begs, like the mysteries of life and death, to be filled in. What’s on the screen is intangible like a shadow, unknowable like a soul. “I wanted to create a daydream on film,” said director Carl Th. Dreyer. Vampyr exists in the space between waking and sleep.

The dreamer is the student, a young man by the name of Allan Gray. His expression is no less neutral than his name. The actor, Julian West, was really producer Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg, who had financed the film on the provision that he be cast in its lead role. I must agree with writer Tony Rayns that “Dreyer makes astute use of his blankness.” It’s at his passive pace that we move between disorientating scenes of ghostly heralds, dancing shadows and premature burial. Only through Gray do we see both worlds. Only by seeing both do we understand the stakes.

“When Americans want to tell people something frightful, they show drops of blood, which drop down on the floor and finally make a pool of blood,” said Dreyer in a 1932 interview. “There is no blood to be seen in Vampyr but one senses blood.”

In keeping with the European vampire myth, the threat to this French town is not physical but spiritual. The damage done to a victim’s body is nothing compared to what awaits their soul. Such a nondescript character rarely makes for a good lead — yet it’s his detached sight of both sides, his willingness to believe, his very malleability, that makes Gray the film’s most compelling character.

Undeservedly but not unsuitably, Vampyr received mixed reviews in 1932. It followed a run of monster films from both Europe and America — including Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein movies, to which Dreyer directed some blame. Critics preferred vampirism as a sickness of the body. They wanted a threat they could see and touch. They couldn’t, or wouldn’t, see what Gray sees, the space between — a world where, in the words of Tom Milne, “nothing, or everything, is real.”

More posts will be passing into the physical world soon — be sure to follow so they don’t slip by you.