Your Health Coverage Will Change. Here’s How.

Texans fall into five groups. Each needs healthcare and will feel the effects if the ACA is repealed. What will it mean for you? A doctor explains.

By Don Kramer

The administration change in the White House marks an interesting time in America, particularly for the Affordable Care Act (or Obamacare). It’s worth looking at the ACA’s impact, especially in Texas, to try to make some projections about the economics of health care in the coming years.

But first it’s helpful to know where we stand globally. Health care spending in the US far exceeds that of other countries: For comparison, we spend about 18 percent of our GDP on health care, whereas France spends 11 percent and the UK spends about 8.5 percent. Our spending is driven primarily by expensive technology, high prices for services, and crazy high prices for prescription drugs. (As an example, I pay $78 for a medicated cream in Paris, where I live. At CVS or Walgreens, the cash price for the same medication is almost $1,600.)

These costs have far-reaching economic consequences. To understand how they will affect people, let’s first break the population of health care beneficiaries in Texas into five groups.

There are about 30 million people in the state, 3.7 million of whom are covered by Medicare, the federal plan for seniors and permanently disabled.

The next 15.3 million people (more than half of Texas’ population) are covered by employer-sponsored group health insurance. Under the ACA, companies with more than 50 employees are required to provide health insurance to their employees who work more than 30 hours per week. Concerns were raised with the passage of the ACA that employers would not be able to manage that financial burden.

No doubt, to offset the rising cost of premiums, employers like myself are buying higher deductible plans and shifting more of the costs onto employees. From the employee’s perspective, since 2006, health care expenses as a percentage of family median income for Texans have increased from 6.5 percent to 10 percent. Employer purchased group health insurance premiums for families in the United States are now in excess of $16,000 (which is shared between employer and employee). For a worker earning minimum wage of $7.25/hour over a 2,000-hour year, that premium now exceeds the worker’s annual wage.

The third group is the population that the ACA was intended for. It gives people the ability to buy individual health coverage plans through insurance exchanges, also known as the ACA marketplace. It’s aimed at those who are not eligible for employer-supported insurance and yet are not poor enough to qualify for Medicaid.

As of August 2016, 20 million Americans have purchased insurance from health exchanges as individuals or families, without exclusion for preexisting conditions. In Texas, 1.3 million purchased coverage from the health exchange, up 13 percent from the year before. So far in 2017, 12 insurance carriers have signed up to sell their plans to individual Texans through the marketplace, but a number of insurance carriers have also recently left because they say they’ve been unable to make a profit.

The ACA promised insurance carriers that the federal government would reimburse losses, but Congress has passed legislation to block those payments. Insurers have filed lawsuits, but a recent federal ruling suggests the outcome may not be what insurers would hope. Currently, insurance companies claim they’re owed about $12 billion. As a result, Aetna, Cigna, and United Healthcare exited the Texas marketplace, and Humana left Harris County. The remaining insurance companies have dropped their PPO plans and now only offer HMOs, which many say is a sign the health insurance exchanges are falling apart.

Regardless, the impact of this is enormous. People will no longer be able to receive their care from providers that are not on the HMO panel. If you were in the middle of a treatment plan for a serious condition, such as cancer, this can be devastating. In Houston, MD Anderson and Texas Children’s Hospital are reputed not to sign contracts with HMOs that offer substantial discounts to the rates these premier hospitals charge.

Currently 87 percent of individuals who buy plans from the ACA exchange receive some amount of federal subsidy, which is calculated based on a ratio of a person’s income to the federal poverty level (FPL). Those subsidies are quite large, bringing the actual cost to a Texan down to $87/month, versus $600/month for an individual or about $1,400/month for a family without a subsidy. But here’s the kicker: One must earn at least the FPL of $11,000 per year for an individual (more for families) to be eligible for the subsidy. So what happens if you make less?

That brings us to our fourth group: The uninsured.

Since 2013, the percentage of uninsured Texans has dropped from 27 percent (the highest in the nation) to just 16 percent (still the highest in the nation). Minorities, especially Latinos and blacks, are disproportionately uninsured. For example, 32 percent of Latinos in Texas lack health insurance.

But why is this? It’s in part because there is a gap between those who can afford to purchase insurance on the exchange and those who qualify for Medicaid. In the middle are those who make too much money to qualify for either an ACA subsidy or Medicaid but make too little to afford individual coverage. That gap was supposed to be addressed by an ACA provision whereby states would expand their Medicaid plans to cover those individuals, and the federal government would pay 90 percent of the cost.

In June 2012, the Supreme Court struck down this provision because it made Medicaid expansion mandatory. Instead, it became optional. Nineteen states, including Texas, then chose to opt out of Medicaid expansion and rejected the federal dollars that would have come with it.

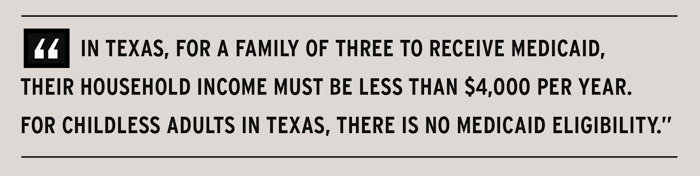

Let’s look at the impact of that decision. Texas has the strictest Medicaid qualifications in the country. In states that expanded Medicaid coverage under the ACA, a working poor family that earns up to 138 percent of the FPL (or $27,821 for a family of three) would be eligible for Medicaid coverage.

In Texas, however, according to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation, for that same family — a mother and two children, for example — to receive Medicaid, their household income must be less than $4,000 per year. In other words, to qualify for Medicaid in Texas, a family of three cannot make more than 19 percent of the federal poverty level compared to the 138 percent requirement of other states. For childless adults in Texas, there is no Medicaid eligibility, no matter how little one earns. In states that took the expansion, individuals who earn less than $16,000 qualify for Medicaid.

That’s why more than 4.8 million Texans — including 623,000 children — lack health insurance. A whopping 47 percent of Texans with household income below $20,000 — the FPL for a family of three — remain uninsured according to a report by Rice University’s Baker Institute.

Texas hospitals continue to shoulder the burden of providing health services to those without insurance. In Houston, for example, those costs get passed on to the Harris County Hospital District and then to its taxpayers. Texas’ decision to reject the Medicaid expansion program prevents the state from receiving an estimated $100 billion in federal funds over a decade. At the same time, Texas hospitals are providing $5.5 billion in annual care to the uninsured.

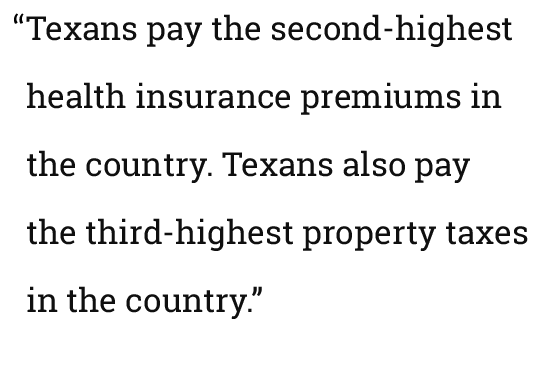

Let’s look at it another way: Texans pay the second-highest health insurance premiums in the country. Texans also pay the third-highest property taxes in the country. Last year in Dallas, Parkland Memorial Hospital took $585 million in property tax revenues from Dallas County to cover its costs of providing uncompensated care. In Houston, the Harris Hospital District took $635 million in property tax revenues. These are monies that the federal government would have largely reimbursed through Medicaid expansion. Combine this with the fact that our state does not allocate state revenues to pay for uncompensated care, the obligation to pay falls to local taxpayers. Since 2012, Harris County property tax levies have increased 43 percent, and more than one quarter of those tax revenues go to the Harris Hospital District to pay for uncompensated care.

Let’s look at our fifth and final group, the 4.8 million Texans who do receive Medicaid.

Over the past 10 years, the cost to the state per Texan covered by Medicaid has risen only 10 percent. How is that possible? Part of that answer is that most Medicaid recipients have been shifted into managed care programs. The other part is that Texas just refuses to pay more, and it also pays for fewer services. As a result, the payments to providers no longer cover the costs of providing that care. While in 2000, 67 percent of providers in Texas accepted Medicaid, today fewer than 30 percent do. Texas is a big state, and we have areas in Texas where you cannot find a provider for a Medicaid patient. On top of that, as previously explained, qualifying for Medicaid in Texas is difficult.

But here’s another interesting point: When the ACA was being proposed, it was said that people would be able to keep their doctors. However, when states get to set the payment rates, no one in the federal government can make that guarantee.

So, where does this leave us under the new Trump administration? One can look at the proposals made by Rep. Tom Price, M.D., President Trump’s new Secretary for Health and Human Services, the agency that oversees the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the administration of the ACA. Let’s see how his proposals would affect our five groups to gain some insight into what to expect during his tenure:

1. Medicare Recipients

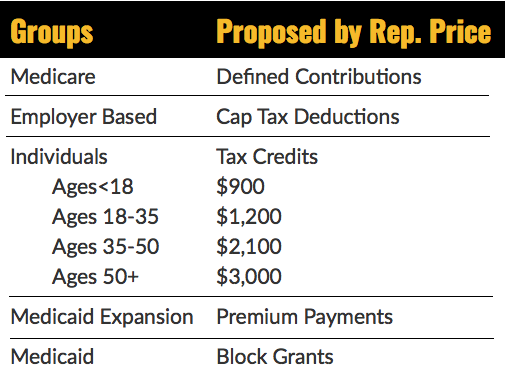

Secretary Price has supported changing the current Medicare program from one where the federal government pays open-ended costs for health care (called a defined benefit) to one that gives each beneficiary a fixed amount of money each year, which could then be used to buy private health insurance (known as a defined contribution). This is essentially what happens now for the 30 percent of seniors who are enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.

2. Employer-Sponsored Group Coverage Recipients

For this group, Secretary Price supports President Trump’s goal to allow insurance companies to sell policies across state lines and says doing so would encourage competition and lead to lower prices. Opponents say such a plan would hurt consumer protections by allowing insurance companies to register their products in the most unregulated states and that consumers would lack recourse through their own state’s insurance commissioner.

In fact, most companies, especially large ones, are actually self-insured, and insurance companies — Aetna, United, or others — are really only providing administrative services, so these plans would be unaffected by allowing sales across state lines. Additionally, a number of states already allow out-of-state insurance sales, but that has not been popular with insurance companies, and they don’t endorse this plan.

Secretary Price also advocates capping the deduction that employers can take on funding their health insurance premiums. This exclusion is one of the largest deductions in the federal tax code, and it costs the federal government an estimated $260 billion a year in foregone revenues.

3. The Self-Insured

This is the 20 million Americans who purchase individual through the exchange. Secretary Price proposed legislation in 2015 that would repeal the ACA and offer this group a tax credit that could be used to purchase private health insurance. Interestingly, he tags this benefit to age rather than income. The proposed tax credit would be $1,200 per year for people up to age 35 and would progressively increase to $3,000 per year for those over the age of 50.

Secretary Price’s proposed plan also eliminates the requirement for insurance companies to cover pre-existing conditions for anyone who has not had 18 months of continuous insurance coverage. Those with care denied for a pre-existing condition could enter a high-risk pool with substantially higher premiums, which may make insurance unaffordable for many. Recently, Speaker Paul Ryan suggested that the federal government would provide subsidies to those in high risk pools, but we don’t know what those amounts would be.

4. The Uninsured

For insight here we can look to Seema Verma, selected by President Trump to lead the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Ms. Verma is a health care consultant from Indiana where she designed the state’s Medicaid Expansion Plan with the support of then-governor Mike Pence. Participants in Indiana pay an income-based contribution into a savings account each month that’s akin to a premium. Failure to pay means losing benefits or coverage. There’s also a penalty charged for using the ER for non-emergencies.

Pence and Ms. Verma said the plan would make people act more responsibly in seeking health care. Proponents call this putting “skin in the game,” but a study published by Dr. Laura Dague, an economist from Texas A&M University, showed that requiring a premium payment — even $10/month — significantly decreased program participation. The drop-off was not related to the size of the premium payment, just to the perceived burden of having to comply. This Indiana program was the first time that CMS let a state lock out Medicaid beneficiaries from coverage, even temporarily. Other states are considering applying for similar programs.

5. Medicaid Recipients

The federal government currently pays 50 percent of the cost of care for Medicaid recipients, and states pay the other half. Dr. Price would like to give the states block grants to replace what the federal government currently pays and shift the remaining expense to the states.

Essentially, the Federal government wants to get out of assuming the risk that comes with providing care for which it has little control. Instead, it wants to give defined annual contributions per beneficiary and shift the risk onto the states.

It may be easy with the recent national election to think that the solutions to our healthcare problem can come from federal legislation alone, but this is wrong. In Texas, the legislature and governor need to be engaged. They have legislated based on principle, but that has not benefited our taxpayers because while health services do get administered in Texas — often through the ER, which is inefficient and expensive — the taxpayers are the ones who’ve been footing the bill.

And that may not change anytime soon. On January 21, President Trump signed his first executive order, which attempts to scale back the ACA. While not directly stated, many suspect the order will weaken the ACA’s central feature, the individual mandate. Without it, young, healthy individuals will likely choose not to buy insurance, which will shift the risk profile to older, less healthy individuals — many of whom have pre-existing conditions. If companies can’t underwrite profitable insurance plans, they’ll stop offering them. In Texas, we’ll know which carriers are in and which are out by May 31. If there isn’t a comparable replacement available by open enrollment in November, we could find ourselves in the center of a brewing crisis.

Donald Kramer, M.D., is the founder, past CEO, and current chairman of the board of Nobilis Health Corporation. He is a board-certified anesthesiologist and serves as the consul for the Republic of Botswana, where he helps develop public health programs. He received his BS from Penn State, his M.D. from Jefferson Medical College in 1981, and his MBA from the McCombs School of Business in 2011. He resides in Paris, France.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily The University of Texas at Austin.

Originally published at www.texasenterprise.utexas.edu on February 22, 2017.

http://www.texasenterprise.utexas.edu/2017/02/22/aca/your-health-coverage-will-change