The Perfect Shot | conversations at nighttime

His sentences became senseless mumblings, and at last he said to me, Du gehst mir auf den Keks: you are getting on my nerves.

A story? At such a late hour? Ah, your opinion of me is too high. No no thank you, all that whiskey doesn’t sit well with me at all.

What, already my turn? Well. Well I guess I’ll have to make do with what I promised? I would hate to ruin this night…No of course not! And the waves do seem very inviting from the deck. It doesn’t look half bad if I drown of embarrassment there, eh?

Quit your bickering now, I’ll tell a story alright. I’ve had my fair share of adventuring before I settled. Ay, you heard it right! I’ll tell you now:

During my student years in Vienna, I found myself in places I really shouldn’t be, and meeting people I never sought to ever encounter.

See, it was a time when everything was brighter, and new fortunes seemed just around the corner. Wherever these new treasures were, they certainly weren’t hidden in the tight hallways and narrow doors of boarding school: by Jove, that place was dreadful even in memory! The professors smelled of salted herring and a few looked like they escaped from the mortician, and the windows! Anyhow, I knew my Pa paid a fortune for that school: and with the benefit of boarding came the freedom to do whatever I pleased during the extended times of liberty.

I picked up a small hustle selling matchsticks to coated and gloved gentlemen at a nearby train-station, and soon collected enough schillings to get a camera. That was the beginning of it all. There was that wonderful and terrible tingling sensation which runs down your spine and back up: when a youngster realises that the world was just beneath his fingertips, all its finest for him to keep with the release of the shutter.

For most of the nights I snuck out under the guise of several overcoats(large enough to conceal my precious camera) and a pair of spacious leather boots, intentionally left unpolished so that I blended right in with the stream of hungry clerks and lawyers and whatnot who stumbled through the wet streets and into various bars and nightclubs for their winding-downs.

I adored the pubs and the bars, especially a place near the junction of Quellenstrabel and Gudrungrom, which the locals referred to as ‘Möllersdor’, or just ‘Möllsdor’. Not because I liked to drink, mind you. I didn’t care a single groschen for the drinks: but rather, it was the drinker which piqued my intense interest.

When I remark that you can catch any kind of person there, take my word for it. The place was a lively as anything, and the quartet would be asked to play once the stars are fully out and the main audience settled down from their clamouring and shufflings into their polished wooden seats. The muddied snow slushed against the stone steps and a most curious smell of old oak wafted between the godly wisps of smoke which billowed up from newly baked Appel Strudels and Weiner Schnitzels — a mixture of spices and heat that held the frigid winter air at bay in the windows. It wasn’t only German conversation, but Dutch and French and Italian all the other languages which I could not care to recognise(Or could not, for I almost always took naps during linguistics). Soon the floor would be cleared for dancing, and the tunes of a polka or a waltz rose in unison with the crackling of the wood-fires.

By then, everyone would be too drunk, too droopy or too senselessly gay to notice a clumsy ‘gentleman’ in unpolished boots, busy fumbling in his thick overcoats. To me, it was a haven of drama and portraiture: I caught ladies twirling with their partners: their heavy winter garments seemed so at ease that I wanted to be swept along into that mass of activity and action — till a newly arrived personage let in a blast of bone-chill from the door which forced me to push up my collars a bit more. The wrought-iron chandeliers swinging from the sudden updrafts provided a landscape of shadows and light which I have never before witnessed. Under that flickering light I caught derby hats and trilby hats and no hats all the same — there was something in taking shots which I so adored. It was almost as if by observing and keeping, I lived all their lives at once.

One winter’s eve when I set up in my usual spot, I noticed an unusual figure toward the opposite of the room. There is nothing out-of-place when one observes trench-coated, tightly-wrapt figures in the middle of winter, but it was not his simple attire which caught my eye, but how he moved. A sharp strike into his pocket to fetch a small box, and a stiff withdrawal of a single, bent cigarette. All done with decisiveness and control like a Spartan pulling an arrow from his thigh. The man proceeded to hold the little roll of tobacco and paper up in the light, before deeming it worthy of being lit by his lighter. This matter settled, our Spartan proceeds to fall back into his ‘relaxed’ form — that is, as ridged as a lone pine in a snowstorm.

I must’ve been staring for a bit of time, for as I turned his eyes met mine and I felt a sudden tremor in my chest, akin to being hit square in the ribs by a pitcher’s ball — as if an invisible snapshot of myself was lifted from my current visage and forever kept in those deep, dark eyes. I shuddered, and turned away in cowardice. Suddenly, a part of Möllsdor was closed off to me, and I snuck back earlier that night than ever before.

Since then, that tall, imposing figure was always present whenever I was present. Always along, he would be at a table or between a throng of workmen. By this hour, I knew that he was probably as aware of myself as I was with him: but there was never an intention to make a move. I could tell that he was intent on observing me and observing only, so it only disoriented me more when I was given a sign to approach.

Immediately the room seemed to dissolve into monochrome and then into darkness, and it was only us: each occupying an extremity of the space available. The man made another sign, more beckoning than anything else. I was trembling, for I dreaded the thought of being captured by one of my masters, especially Herr Guttenhumier, the school deputy who was rumoured to lie undercover in order to catch students out-of-character. But as a covered the distance between us I could tell that what I beheld before my eyes could not be Guttenhumier: this man was much leaner in form. But then the thought of the unknown only thew my mind into further chaos.

All along my body weaved between waiters and dancers and carousers, careful not to foil my own guises while appearing as comfortable as possible. Until at last, crossing a minefield of spilt wine, I reached the strange man’s table. He gestured to a chair, which I gingerly took, and at last I would get a glimpse of that figure which I was so curious to explore.

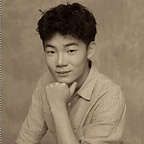

Clean cut lines where wrinkles faded into flesh. Face ruddied from the wind, eyebrows like forests bordering two deep, deep lakes. His nose was swollen and there was loose skin where blisters once bloomed. All the wild, unkempt strength of slavic features. He kept some sort of beard, but even at that distance the light was too dim for me to distinguish.

After a long silence, he finally spoke:

“It is good night, is it not?”

He spoke in heavily accented German, with a deep rumble which gave impressions of a shaggy bear treading on ice. I replied that the night was wondrous. I tried to keep my voice low. He seemed to take in my comment, and proceeded to talk.

“I notice you every night: you don’t act like anyone else. I am curious. What brings you to hearty Vienna?”

It was at that moment that I realised: if I wished to preserve what remaining disguise I had, I needed to become a familiar character, and fast. So I did: and Eustace Murdoch because Ulbrecht Weber — a photography student cum temporary Viennese resident, here at the Möllsdor to take shots for an exhibition. I turned to the stern fellow:

“Yes…yes I take shots: I take shots of people for contractors who are interested in my work.”

“Shots, did you say?” And at this the man laughed: a deep-chested, creaking laugh, “Ho-ho. And after all this time. I have finally found friend.”

At this gesture of kindness, I left behind all doubts. I, too, longed for conversation on the topic of taking a perfect shot in portraiture — conversation which no one within my vicinity seemed to care for. Finally, my work was noticed by someone! Maybe this is a professional lensman…or a real contractor who can teach me wonderful things I’ve never dreamt of learning before!

“Dear me! You must be most experienced in this area, then? I am really most passionate about taking that ‘perfect shot’ — you know, that one second where everything is suspended in perfection?”

“Of course, my friend. But tell me: what subjects do you like the most? Men? Women? “ At this he paused a little, “Children?”

“Anyone I can catch, really. It is so difficult to set up a proper position when they are wandering strangers.”

“Ah. I see what you saying,” He paused and looked around: the bear is scanning for danger. He took out a cigarette and took a long draft. “But friend, remember it is all about angles. Every shot you take must have purposeful intent, you see.”

“But I thought it was the free-angles which are the most popular: shots of life and moments easily gone by are the most prized in the papers.”

His face suddenly dropped at this.

“The papers? When did shots go on papers? I do not remember such a thing in my time.”

Rather old fashioned.

“But sir, the papers are full of the men, women and children all around us. Have you not seen?”

“Nein. Things changed since old time. I keep my shots to myself, in sealed paper bag. Must take work seriously, not folly. ”

We talked of lighting, of weather and of steady hands. But the more I told him of modern practices, the most frustrated and alarmed he became. His sentences became senseless mumblings, and at last he said to me, Du gehst mir auf den Keks: ‘you are getting on my nerves’.

We must’ve been sitting for an awfully long time, for the general assembly has long since trickled away into the dead of the night: leaving trails of colourful wrappers and mud upon the freshly lain snow. A storm had swirled up outside. The old man pushed away from the table and crushed the cigarette head between his thumb and index finger.

It was then when I caught it: dark grooves at the base of both his thumbs. They looked like old wounds. No longer swollen, but the dents on the nails which refused to heal were enough to describe the sudden and brutal force of that contraption which inflicted upon them such a crushing blow.

He tightened his coat, and, taking further notice of me, uttered a forced goodbye and made for the door. Something stirred in the back of my mind. I stumbled after him, past the door and into the dim street.

“Sir! I am looking for that flawless photograph, my perfect shot! But Sir, are you also — “

The frigid air stung my lungs, and that was when I remembered the lecture of the history master a few nights ago:

“…The early designs for the Mosin–Nagant lacked a guard function for the chamber door……and so the unaware Soviet sniper, reaching in to reload the cartridge in mind of time, would have the metal blunt his finger in a single, agonising blow.”

The shadow before me stopped in his tracks for a while, as if he was waiting for me. And then he disappeared altogether into the snow.

I fumbled for the camera, and shot blindly into that vast void: A dark silhouette against the backdrop of a darker night.

A perfect shot indeed.