Concepts Without Context

Why you cannot understand the 2nd Amendment without knowing history

This post is the the first in a series provided by a friend of The Agoge and a “friend of the people,” who goes by the nom de plume ‘Publicola.’ This post originally appeared in another, now defunct, blog in 2013.

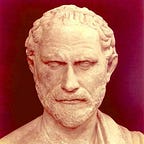

“On every question of construction (of the Constitution) let us carry ourselves back to the time when the Constitution was adopted, recollect the spirit manifested in the debates, and instead of trying what meaning may be squeezed out of the text, or invented against it, conform to the probable one in which it was passed.”

— Thomas Jefferson, letter to William Johnson, June 12, 1823

Every time the debate about gun control rages, there is invariably a myth that is dusted off, shined up and placed on display to be referred to by every misinformed commentator. The text of the 2nd Amendment is invoked to argue that the Founders only intended “the militia” (implied to mean an organized militia, as in something akin to the National Guard) to keep and bear arms. In actuality, this very wording proves precisely the opposite.

But this is only evident to those who understand that words are merely tools, used to convey meaning. This is a simple concept that can be seen easily with differing languages. The word “gift” has a meaning in English, but the same arrangement of letters means “poison” in German. The language in which a word is used, its context, affects meaning. And context is determined by time as well as language. In the U.S. in the 1950s, the word “gay” had a drastically different meaning than it does today. A contemporary viewer, watching a movie from that decade without understanding this, would be greatly confused if one character referred to another as gay.

This, then, is the same same situation that occurs when one tries to interpret the text of the 2nd Amendment with no understanding of history. What emerges in this interpretation is a sort of halfway position between adhering to the text (emphasizing one portion and ignoring another) and imposing a different (more modern) interpretation on it, rendering it contrary to its actual intent and how it was understood at the time it was ratified. To understand what the Amendment really means several complimentary approaches can be used.

1. Common Sense. The system of government set up by the Founders was based on the political philosophy of individualism, that individual rights are sacred and the basis for society (hence our Bill of Rights, hence limits on the power of the government and limits on the power of the majority). So averse were the Founders to collectivist government that the word democracy does not appear in the Constitution once, but a variation of republic (a form of government based on individualism, with guaranteed protections of rights) does, twice. Franklin, when exiting the convention and asked what government was created, famously replied, “A Republic, if you can keep it.” Why would these men, after creating a whole structure based on a political philosophy of individual rights suddenly and for only only one critical right, shift into a collective mode of thought? The right to free speech is certainly not a collective right (groups benefit from it, but it is not limited to them).

The purpose of the right can further be deduced by looking at another of founding document, penned by Thomas Jefferson:

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, —That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness … But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”

Why would men have proclaimed the right and duty of a people to overthrow a tyrannical government, but at the same time deny them the means to do so?

Critics of this view ask why the Constitution gave the power to “suppress insurrection” to the federal government, if it wanted the people to be able to overthrow a government. This simplistic view assumes that there cannot be both legitimate causes of revolt and illegitimate ones. It was expected that unlawful movements that did not represent the will of the whole people, like Shay’s Rebellion, would have to be put down by the government, but it was also assumed that when a government crossed into tyranny, then the armed populace rising against it would consist of a much greater part of the population, and the government would not be able to resist it. The ability to suppress rebellions was added to protect the republic from domestic insurrection, but arming the populace to make the government vulnerable to the people, and thus more accountable to them was also means of doing the very same thing.

2. The text. “A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

The Framers were incredibly specific and very detail-oriented in creating the Constitution. They haggled over every sentence, every word, every piece of punctuation in Constitution. In fact, the deliberate change of a comma to a semicolon in one version of the draft was an attempt at expanding the central governments power and almost changed the meaning of the document, until it was caught and corrected. With this in mind, why would the Framers grant “the people” the right to bear arms and not “the militia” if that was their intention? The point is made very forcefully by Penn Jillette in this short clip.

Understanding the real meaning of the text requires a knowledge of history. At the time of the Founders, the distinction between the individual and the militia did not exist. The militia was a compulsory and universal system, not something separate from the individual. There was no distinction between the militia and the people and the concept of the militia as an actual separate entity did not exist until after the war of 1812.

This idea can be witnessed in several examples from the time:

- The first draft of the Amendment was actually worded after Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, and it began, “A well regulated militia, composed of the whole body of the people…”

- During the debates George Mason, made this point explicitly: “Mr. Chairman, a worthy member has asked who are the militia, if they be not the people of this country, and if we are not to be protected from the fate of the Germans, Prussians, &c., by our representation? I ask, Who are the militia? They consist now of the whole people, except for a few public officers.”

Congress actually rejected the wording that stated “to keep and bear arms for the common defense” to ensure that the right was seen as an individual right, not simply as part of national defense. Interestingly, this same debate was had regarding the English Bill of Rights of 1689, but in that case as well, the individual right wording won out.

3. Historical Context. At the time of the founding there was a tradition of individual rights to weapons. The Framers based their philosophy on a long history of English law (among many other philosophies) and in this area the right to keep and bear arms has been very present for a long period of time.

- English common law always allowed a right to keep and bear arms, and in fact doing so was required for most of English history (as it was a necessary part of feudal society).

- This right was protected in an un-named charter by Henry II in 1154.

- The 1215 Magna Carta ensured the right of individuals to revolt against the government if their rights were not protected — this right not only implies but necessitates a right to keep and bear arms (so also with the Declaration of Independence).

- Disarming of English citizens and raising of a large standing army and tyrannical treatment of citizens by King Charles II and King James II resulted in the English Bill of Rights of 1689 which guaranteed no royal interference in the freedom of the people to have arms for their own defense. This would later be a major influence on the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and US Bill of Rights.

This is an outstanding article highlighting this long tradition.

4. In Their Own Words. If the Founders intent for the right to bear arms to be an individual right for the purpose of defense against tyranny is not obvious enough at this point, statements that they and others of the time made make this clear.

* It must be noted most of the statements are in the context of a debate between a standing army and the militia, but as already discussed, the militia was viewed as the people and the argument for a militia to be armed to protect against a standing army only further demonstrates that the intent was that the people be armed as protection against the government:

“And what country can preserve its liberties, if its rulers are not warned from time to time that this people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms.” — Thomas Jefferson in a letter to William S. Smith in 1787

“Their swords, and every other terrible implement of the soldier, are the birthright of an American… The unlimited power of the sword is not in the hands of either the federal or state government, but, where I trust in God it will ever remain, in the hands of the people.”

— Tench Coxe, Pennsylvania Gazette, Feb. 20, 1788

“Guard with jealous attention the public liberty. Suspect everyone who approaches that jewel. Unfortunately, nothing will preserve it but downright force. Whenever you give up that force, you are inevitably ruined.”

— Patrick Henry, Debates

“…to disarm the people — that was the best and most effectual way to enslave them.”

— George Mason, Debates

“The great object is that every man be armed…everyone who is able may have a gun.”

— Patrick Henry, Debates.

“As civil rulers, not having their duty to the people before them, may attempt to tyrannize, and as the military forces which must be occasionally raised to defend our country, might pervert their power to the injury of their fellow citizens, the people are confirmed by the article in their right to keep and bear their private arms.”

— Tench Coxe, `Remarks on the First Part of the Amendments to the Federal Constitution,’ Philadelphia Federal Gazette, June 18, 1789

“Besides the advantage of being armed, which the Americans possess over the people of almost every other nation, the existence of subordinate governments, to which the people are attached, and by which the militia officers are appointed, forms a barrier against the enterprises of ambition, more insurmountable than any which a simple government of any form can admit of. Notwithstanding the military establishments in the several kingdoms of Europe, which are carried as far as the public resources will bear, the governments are afraid to trust the people with arms…”

— James Madison, Federalist Papers #46

“The right of the people to keep and bear…arms shall not be infringed. A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people, trained to arms, is the best and most natural defense of a free country…”

— James Madison, I Annals of Congress 434 [June 8, 1789]

“A militia, when properly formed, are in fact the people themselves…and include all men capable of bearing arms.”

— Richard Henry Lee, Additional Letters from the Federal Farmer (1788)

“The right of the people to keep and bear arms has been recognized by the General Government; but the best security of that right after all is, the military spirit, that taste for martial exercises, which has always distinguished the free citizens of these States….Such men form the best barrier to the liberties of America”

— Gazette of the United States, October 14, 1789

“The whole of the Bill (of Rights) is a declaration of the right of the people at large or considered as individuals…. It establishes some rights of the individual as unalienable and which consequently, no majority has a right to deprive them of.”

- Albert Gallatin of the New York Historical Society, October 7, 1789

“No Free man shall ever be debarred the use of arms.”

— Thomas Jefferson, Proposal Virginia Constitution

“No kingdom can be secured otherwise than by arming the people. The possession of arms is the distinction between a freeman and a slave. He, who has nothing, and who himself belongs to another, must be defended by him, whose property he is, and needs no arms. But he, who thinks he is his own master, and has what he can call his own, ought to have arms to defend himself, and what he possesses; else he lives precariously, and at discretion.”

— James Burgh, Political Disquisitions: Or, an Enquiry into Public Errors, Defects, and Abuses [London, 1774-1775]

“The people are not to be disarmed of their weapons. They are left in full possession of them.”

— Zachariah Johnson, Debates

One may say what they will about whether citizens should or should not be allowed to possess firearms, but one thing that cannot honestly be said is that that the Framers did not intend for it and that the Constitution does not allow for it.

(Coincidentally, the courts have consistently upheld this view as well, but that is a matter for another post)

-Publicola