The History Boys: Henry VI, Part Two

Hang on a second, did I get my chronology wrong here? How come I appear to have skipped Henry VI, Part One and gone straight to Part Two? Well, the scholars seem to agree the Parts Two and Three were the original works and then Part One was a later prequel. A version of this play was published in quarto format in 1594 with the somewhat unwieldy title The First part of the Contention betwixt the two famous Houses of Yorke and Lancaster, with the death of the good Duke Humphrey: And the banishment and death of the Duke of Suffolke, and the Tragicall end of the proud Cardinal of Winchester, with the notable Rebellion of Jack Cade: and the Duke of Yorke’s first claim unto the Crowne. That ‘First part’ indicates the primary nature of this play in the sequence and the title gives a pretty good summary of the main events in this pretty long play (the film version clocks in at three and a half hours). So it looks like Shakespeare did a George Lucas here and wrote a successful play, following up with a sequel before deciding that maybe he needed to go back and tell the lead up to the story first. I’ve never read or watched the Henry VI plays before, so here’s hoping Shakespeare did a better job of the prequel than George Lucas did with those horrible Star Wars films.

Young Will had shown some talent for comedy in his first couple of plays, both of which were set in Italy (although, really, they could have been set anywhere — there’s not much in the way of specific detail about Verona or Padua in them). Now he must have decided to have a stab at an English story and what better place to look than the history books. Specifically Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1587) and the earlier source (which Holinshed himself borrowed liberally from), Edward Hall’s The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancaster and York (1548). The epic upheaval that constituted the Wars of the Roses seemed like the perfect opportunity. Here was an England torn apart by rival factions, taking advantage of a weak king to plot against each other. There could be battles and intrigues as well as insults against the French. He could even incorporate the lower classes as well as the nobility, primarily through the rebellion led by Jack Cade.

The BBC version of Henry VI, Part Two was broadcast in January 1983 as part of Series 5 and was directed by Jane Howell as part of the tetralogy of the three parts of Henry VI and Richard III. The four films were made at the same time with cast members continuing roles across the series. Peter Benson plays the weak King Henry VI, who had attained the throne at just nine months of age after the untimely death of his father, the heroic Henry V who had conquered France.

It’s unclear (to me at least) how old Shakespeare was wanting King Henry to be in the play, but it begins with Henry’s marriage to Margaret of Anjou, which in reality occured in 1445 when Henry was 24 and Margaret 15. Peter Benson was 39 when this film was made, so he looks a little out of place as the young and naive king who is still assisted by a ‘Protector’ at the beginning of the play (although he needs to play the older Henry in Part 3 as well).

The marriage doesn’t go down too well with the other nobles as Suffolk has managed to swing a remarkable deal that not only sees Margaret come without a dowry but also sees Henry lose the lands of Maine and Anjou in France. Everyone seems pretty upset about the situation, but particularly York who gets his own soliloquy to reveal his plans to take the crown for himself due to an argument about lineage that will make more sense after you’ve seen Henry IV, Part One, but Shakespeare won’t write that for five years or so yet. It looks like it’s all going to be on between the Yorks and the Lancasters: white roses versus red roses. But not for a few more hours yet, because there’s other stuff that Will wants to tell us about. Lots of other stuff. Like I said, this is a pretty long play.

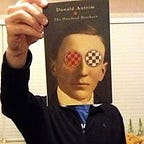

Interestingly, one of the complaints about Henry as king, apart from the fact that he’s really not as good as his dad (but then people thought his dad was a dud too, while he was prince — see Henry IV, Part One), is that he reads too many books: “bookish rule has pulled fair England down.” We’ll see this echoed later in the play when Jack Cade goes on the rampage. He also bangs on about God all the time, which I guess could be appropriate for someone who is supposed to be God’s representative on earth, but really people want a king who’s going to go out and kill some Frenchmen instead of staying at home reading the Bible and wringing his hands (see portrait above).

One of the things that Henry fails to do is protect his Protector. His wife Margaret says that he’s a big boy now and doesn’t need a Protector anymore, and Suffolk and Cardinal Beaufort hate beardy old Humphrey the Duke of Gloucester anyway, so plans are made to undermine him. First they catch his wife trying to get a bit of witchcraft going and manage to have her exiled, which Humphrey is forced to support. Then they turn on Humphrey himself, get him thrown into prison and then Suffolk hires a pair of murderers to do away with him. We’ll see this done much more efficiently in Richard III, because Suffolk is really just an apprentice villain without the truly evil skills of Richard with his hunchback and withered arm. Everyone, even the king (and that’s saying something), immediately knows that he’s responsible, so he gets exiled and the Cardinal gets an attack of the guilts, starts raving and seeing ghosts and then dies. Oh and Suffolk gets captured by a band of ruffian soldiers and has his head chopped off.

There’s other stuff to do with alliances being formed and York heading off to Ireland with a band of soldiers to crack a few heads before coming back to use those soldiers to start a full-fledged rebellion against the king, but the really interesting stuff that brings the play alive is the rebellion of Jack Cade, which we see in Act IV. Shakespeare suggests that York was behind the whole thing, hoping to create some mayhem while he was out of the country, so he could come back and press his claim more easily. Jack Cade is a force of nature, though, a rabble-rouser who gets the commoners behind him through appeals to their baser natures and a willingness to chop people’s heads off, especially if they’re into all that book learning. It;s during this part of the play that one of Cade’s followers utters the immortal line, “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.” Sound advice for any time or place one would have thought.

When he captures Lord Saye, the charge that Cade lays against him includes the following:

Thou hast most traitorously corrupted the youth of the realm in erecting a grammar school; and whereas, before, our forefathers had no other books but the score and the tally, thou hast caused printing to be used, and, contrary to the king, his crown and dignity, thou hast built a paper-mill. It will be proved to thy face that thou hast men about thee that usually talk of a noun and a verb, and such abominable words as no Christian ear can endure to hear.

The lesson is clear: build a grammar school, or talk about parts of speech, and you die. There are plenty of vicarious thrills in watching Cade run rampant and stick it to those toffee-nosed gits who call themselves noblemen. He even knights himself. Sure, we readerly types might feel a little squeamish about his anti-intellectualism and instructions to “burn the books,” but we know his triumph is going to be short-lived and he’s been abandoned by his fickle followers and killed after going on the run by the end of Act IV.

The final Act eventually gives us the battle that we’ve been waiting for, between the rebel forces of York and those loyal to the king, and it is the rebels who triumph at the First Battle of St Albans. There’s no neat ending so it seems like Shakespeare was already looking ahead for the sequel to this story.

The BBC film was pretty well staged, with a set that apparently gets used across the trilogy of Henry VI plays and decays steadily as the country descends into war. It’s meant to suggest a children’s playground and it’s abstract enough to serve for a range of different locations. The acting is strong, with David Burke as Humphrey the Duke of Gloucester and Dick the Butcher (a number of the actors take on double roles) a particular standout for me. Bernard Hill (who you may recognise as King Théoden in The Lord of the Rings film trilogy) as the rebellious Duke of York is also very strong.

Julia Foster as Queen Margaret gets a pretty juicy role that she’ll carry on in Part Three and Richard III. Shakespeare apparently didn’t look too favourably on Margaret, protraying her as a Machiavellan schemer who conspires with her lover Suffolk and dominates her excessively pious husband. In terms of the development of his female characters she is obviously another character that would be fun to play and she is manifestly a powerful, strong-willed woman, but it’s not exactly a positive portrayal. Women don’t play a large role in the play beyond Queen Margaret, with the notable exception being Duke Humphrey’s wife, Eleanor, who is portrayed as something of a schemer herself, trying to goad her husband towards rebellion against the king as a kind of proto Lady Macbeth.

One thing that struck me about the language of the play was the animal imagery, which Shakespeare really goes to town with. I was familiar with this to some extent from Richard III when I taught that, but that’s comparatively restrained compared to this play. In the space of a few lines in Act III we see that as far as the King is concerned, Gloucester is as innocent “As is the sucking lamb or harmless dove,” but for the Queen, Gloucester is “disposed as the hateful raven” who is not a lamb but is “inclin’d as is the ravenous wolves.” We also get “mournful crocodile(s),” “labouring spider(s),” “starved snake(s)” and a whole meangerie of other animal metaphors. He really needed an editor to cast an eye over this one.

The play as a whole has its moments but is a bit of a mishmash. Shakespeare won’t work out how to do history really well until Henry IV, Part One, I don’t think. But this is the beginning of his examination of Kingship and what it takes to be a strong and effective leader that he will continue throughout the history plays and through the tragedies as well. Incidentally, the legendary literary theorist Jacques Derrida wrote an essay on “Shakespeare’s idea of kingship” back when he was a student. His teacher gave it a mark of 10/20, calling it “quite incomprehensible” in parts. Well, we’ve all got to start somewhere, don’t we?