The Woman Who Fixed Engineers’ Home Improvements

The Haven interrupts its regular publishing to report the death of the woman who repaired, rebuilt, and re-installed DIY projects by homeowners who were engineers. Because the sad fact is, no one does-it-yourself worse than engineers.

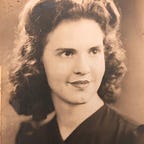

Miss Agnes Manitou was a handywoman on the Leelanau, a peninsula in Michigan’s Up North known for vast cherry orchards, miles of Lake Michigan beaches, and Summer infestations of Fudgies.

Fudgies were southern Michiganders, so-named because, when they vacationed Up North, they bought boxes of its signature candy, Mackinac Island Fudge. The locals liked Fudgies: they liked them to drive up, spend their money, and leave. (They liked a Fudgie subspecies less: the “Seagulls”, so-called because they swooped in, crapped all over everyone, then flew away.)

Miss Manitou liked Fudgies, too: for decades, she earned her living maintaining their Summer cottages.

Some Fudgies didn’t need her help. The “Highlighters,” for instance. They meticulously highlighted the operating, maintenance, and safety instructions in the manuals which came with their appliances, hardware, and HVAC equipment. Organized the manuals in three-ring binders. And referred to them whenever they maintained, fixed, or upgraded their homes. Highlighters were atypical homeowners, in that they knew the locations of their fuse box and main water shutoff valve. Regularly changed the furnace filter, cleaned the clothes dryer exhaust, and lubricated the garage door tracks. And knew how to find wall studs, hang shelves, fix a running toilet, and replace a leaky faucet.

Then, there were the homeowners who often needed Miss Manitou’s help: the engineers. Whether electrical, mechanical, civil, or chemical, they had one thing in common: they thought they knew more about their houses than the manufacturers. As a result, when doing maintenance and repairs, they felt free to take shortcuts. Do workarounds. Use things for off-label purposes. And ignore the manuals.

Miss Manitou agreed that engineers knew more about their homes than the manufacturers. In her experience, only an engineer, when installing a new toilet, could find a way to place the handle inside the tank. Attach the seat cover under the seat. Set the toilet without putting a wax ring on the flange to keep waste water from trickling across the floor. And without removing the rag they’d stuffed down the drainpipe after pulling the old toilet, to keep sewer gas from wafting up into the bathroom.

That said, there was someone worse at home maintenance than an engineer: an engineer who’d moved into Management. It was understandable. As managers, they didn’t have time to keep their engineering skills up: they spent their days wheel-reinventing, dog-and-pony showing, scope-creeping, goal post-moving, pooch-screwing, blamestorming, and under-the-bus throwing. Their “corporate” skills were useless at home: a person can’t “pencil-whip” weatherstripping, “leverage” a leaky toilet, or “empower” a clogged dryer vent. As were their “core” competencies: a manager can’t beguile, bluff, baffle, or bully their house into running properly.

Unfortunately, these managers still considered themselves hands-on engineers. They insisted on doing updates and fixes themselves. That caused Miss Manitou to spend an inordinate amount of time uninstalling their updates and repairing their fixes.

After years of salvaging engineers’ home projects, Miss Manitou got proactive. She gave engineers guided tours to show them the locations of their faucet, toilet, water heater, and main shutoff valves. Provided hands-on training for locating wall studs. Demonstrated the “basics” of using corded power tools (the most basic being how to not cut the cord). Tutored them on how to read manufacturers’ manuals — and take a fluorescent highlighter to them. And for managers in particular, gave them electroshock therapy, no less, to break them of a habit which works in Corporateworld, but not at home: when they screwed up a project, just declare victory and move on.

Through such efforts, Miss Manitou reduced engineers’ calls to clean up their home repair messes by seventy percent.

Unfortunately, she never eliminated one problem: outbreaks of “The Pocks.” “Pocks” are coin-sized indentations in walls which are created by engineers’ repeated attempts to hammer in nails. It can be any kind of hammer: a dainty five-ounce tack; a husky twenty-two-ounce “framer”; or your typical sixteen-ounce “claw.” Regardless, engineers didn’t know how to swing it. They’d “hook” their shots: do an inside-out swing which struck the nail a glancing blow on the right, bending it left. Or “slice”: swing outside-in, which bent the nail to the right. They’d “shank”: skip the hammer off the head, bending the shaft so it couldn’t be driven in. Or whiff: miss the nail completely. And after every bad swing, they’d take a “mulligan” — and make another Pock.

The result was rashes of dimples around nails. They’d blossom on drywall, moldings, doors, paneling, furniture, pets, and spouses. Engineers’ wild hammer swings would also crack nearby lamps, countertops, sinks, mirrors, televisions, pets, and spouses. And strew the floor with fragments of coffee cups, water glasses, plates, vases, cremation urns, pets, and spouses. It was worse if a hammer wasn’t close by: in that event, an engineer would grab whatever was, be it a skillet, free weight, metal baseball bat, or nine-iron.

Miss Manitou held practice sessions to help engineers improve their swings. She’d have them assume the correct stance: back straight, knees bent, feet shoulder-width apart. Grip the hammer firmly. Then swing with hand, arm, and shoulder moving in concert to achieve both power and pinpoint control. But even after a day of training, the results were usually disappointing. As one engineer put it: “If I sliced, the nail bent right; if I hooked, it bent left; if I drove it into the wood, it was a miracle.”