The Woman Who Got Wild Animals To Look Before Crossing The Road

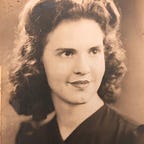

The Haven interrupts its regular publishing to report the death of Mrs. Luella Pixley, whose “Human Crossing” signs on animal trails virtually eliminated roadkill.

Mrs. Pixley was a roadkill specialist on the Leelanau, a peninsula in Michigan’s Up North known for its vast cherry orchards and hundred scenic miles of Lake Michigan shoreline. As was typical Up North, humans were far outnumbered by possums, porcupines, bears, raccoons, woodchucks, coyotes, foxes, squirrels, and skunks. This was apparent to drivers on any given day, when they’d see critters cross the road up ahead — and thunk over the ones who didn’t make it. And sometimes more than a thunk. Deer roamed the Leelanau. They weighed up to three hundred pounds. When they didn’t move fast enough, both car and driver could end up in their respective body shops.

Accidents weren’t Mrs. Pixley’s concern; her’s were the carcasses. SOP was to compost them. Specifically, Mrs. Pixley would patrol the county roads, scoop up the roadkill, and take it to the Road Commission maintenance yard. There, she’d lay the carcasses in a square pit dug in the yard’s back forty, then cover them with a mulch of grass clippings and leaves. When a layer was filled, she started another above it; when the pit was full, she backhoed a new one. As for the carcasses, bacteria and fungi gradually reduced them to nutrient-rich organic matter.

The downside of this strategy, as any backyard composter knows, was that the bacteria had to be nurtured. If it dried out, drowned, or suffocated, it died. The roadkill would still be reduced, but by anaerobic rotting and fermenting, which was slower and far more repulsive.

To determine if the bacteria in a pile had sufficient moisture, Mrs. Pixley performed a “squeeze” test: she plunged a rubber-gloved fist into the pile up to her elbow, grabbed some gunk, pulled it out, and squeezed it into a ball. If the ball crumbled, the pile was too dry; if it oozed, the pile was too wet; if it held its shape, the pile was just right. The test was simple. Also disgusting.

If a pile was too wet or lacked oxygen (the latter based on the degree to which the bits of roadkill in the ball had decomposed), the pile needed to be “fluffed”: Mrs. Pixley had to churn its contents with a spading fork, so as to expose them to the air.

Mrs. Pixley didn’t like fluffing. She liked squeezing less. Nor was roadkill-collecting the high point of her day. Unfortunately, other county road employees wouldn’t do it. She’d gotten her supervisor to offer them half-days off with pay. One-time “Hazardous Duty” bonuses. Or sweeten their hourly rate with “Disgusting Duty” pay. No joy. She even got the boss to announce that underperformers would be made to help with carcass composting. That just motivated everyone to become overperformers.

Then Mrs. Pixley had an epiphany. Instead of collecting, squeezing, and fluffing roadkill, why not just eliminate it? But how?

Perhaps the key lay in answering one question: why do animals cross the road? Wildlife biologists offered their theory: animals like to explore new places; to seek out new food and shelter; to walk, crawl or slither where their species hadn’t gone before — especially if their predators hadn’t gotten there ahead of them.

Leelanau old-timers had a different theory: the animals were looking for “tail.” They knew cars might be on a road. They could see the smears left by comrades who’d tangled with them. They tried their luck anyway. There could be but one reason why critters crossed a road: they were hoping to “score” on the other side.

Unfortunately, neither theory suggested a course of action.

Then, something occurred to Mrs. Pixley. Roadside signs were used to warn motorists that they were approaching animal crossings. They didn’t reduce roadkill. Perhaps that was because the signs were aimed the wrong way.

Mrs. Pixley tried something different. She identified the ten busiest animal trails which crossed county roads. Then she placed “Human Crossing” signs on them. The signs were affixed to wooden posts ten feet short of each road. There were two signs per post: one, five feet above the ground, so as to be seen by deer, bear, and coyotes; the other was three inches off the ground, putting it eye-level with squirrels, skunks, possums, porcupines, woodchucks, turtles, and snakes.

The signs were standard yellow animal crossing warnings, but with just the silhouettes — no words. The silhouettes were Crayola Blue; animals’ eyes are more sensitive to that than black. And Mrs. Pixley overlaid them with a wash of the most pungent pee in the animal kingdom: possum piss. That allowed animals, with their extraordinary senses of smell, to perceive the images in the dark. (Mrs. Pixley harvested the pee herself. It wasn’t easy. But she preferred it to fisting roadkill compost piles.)

As for the images, Mrs. Pixley applied one of the following to each sign.

- A possum in mid-bounce off a car’s front bumper;

- A skunk splayed across an auto’s grille;

- A deer sprawled atop a pickup truck’s hood;

- A look-down view of a flattened turtle with tire tracks across it; or

- A porcupine stuck by its quills to the outside of a spinning tire.

Up North wildlife got the message. As the signs went up, roadkill went down. When the program went county-wide, roadkill became a thing of the past. And so it remains today. That is, except for the occasional mangy old fart who decides it would rather play chicken with a Chevy than freeze its furry ass off in another Up North winter.