“The Dean of New York Labor Historians” on Unions, Labor and The Working Class

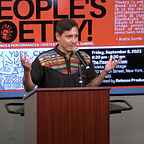

Joshua B. Freeman is a distinguished professor of history at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center and is referred to by his colleagues as “the dean of New York labor historians.” Freeman grew up in the Little Neck section of Queens in the 1950s and graduated from Harvard University in 1970 before going on to receive his Ph. D from Rutgers University.

Freeman’s work as an educator, researcher and author focuses on the labor history and sociology of the working-class. His two most notable books, “Working-Class New York: Life and Labor Since World War II” and “In Transit: The Transport Workers Union in New York City, 1933–1966” are concerned with the historical sociology and labor of New York.

I got the chance to speak with Freeman about his career as a historian and asked him about the current state of labor unions in the United States and New York City. Here is our conversation:

You came from a deep working class background in 1950s New York. Tell me a little bit about your family upbringing and how that shaped your appreciation for the working class?

My grandparents were all working people. My parents grew up in working class homes. They were actually professionals. They had gone to college. My father was a packaging engineer, my mother was a social worker, so you know, it wasn’t that I came directly from a traditionally-imagined working class household, but I certainly grew up through my grandparents and other relatives knowing a little bit about that world. That was always lurking some place within me as I became a historian, and started thinking about what I was going to write about and how to approach the issues.

So was studying history a personal decision for you to make more sense of the way that you saw the labor forces operating in your community?

Well kind of. I wouldn’t say it was an effort to make personal sense of the world I lived in. I think when I approached that topic I was particular interested in what happened to all the dynamism of the labor and other social movements of the 1930s and 40s. When I was growing up as a kid that didn’t seem to be around me anymore. I think the first question that pulled me in that direction of labor history was kind of looking at under what circumstances labor and other social movements developed and what was their quiescence.

Right, and you’ve written extensively on the history of labor unions, specifically in New York. But let’s focus on America as a whole. Labor union membership is at ten percent, and the private sector is under seven. How would you assess these figures and what factors have contributed to these circumstances?

Certainly shifts in the economy, the decline of employment in areas that were traditionally strongholds of organized labor like manufacturing, mining, and the failure of labor to organize some of the growing in rest of the country like the Southwest, the South, and growing industries — tech industries, service industries. This all certainly accounts for a lot of the story. I think this is also a political story of a political culture and a series of administrations that have been quite hostile to organized labor and made it increasingly difficult for unions to organize or to successfully engage in collective bargaining. But what’s interesting is if you look at the polling data over the last few decades, at every moment the number of workers that say they’d like to be in unions fluctuate, but at any moment it’s way, way higher than the number of actual people in unions. So I think the obstacles to forming a union are probably more significant than changing attitudes among workers.

New York is known for being a bastion for organized labor. They have the highest rate of union membership in the country at nearly 25%. Can you talk a little bit about the historical significance of New York in the American labor movement?

Just think of the heads of the AFL and CIO over the years, from Samuel Gompers to John Sweeney to George Meany, have been New Yorkers. New York’s been very important. I think that has to do with a lot of things. One has to be the political climate has been liberal in New York and there’s been a lot of activity by working people themselves. They have forced employers to recognize unions and forced government to pass pro-worker legislation. The causes? Well, New York is a town of immigrants and new immigrants often bring progressive ideas with them. Also, generally employers here have not been as hardline anti-labor as in some other parts of the country.

And you see a lot of talk now about unions from the left politically, especially in New York City. Are you hopeful that this is bringing working-class families back to the table?

One of the interesting things that’s happened over the past few decades is that the labor movement’s lost power has some how kind of moved to the left. And I think the power of labor in some ways has continued in the political arena even as sometimes in the work place and the economic arena it’s diminished. I think the New York Governor’s race shows you how much the pull from unions and other groups is to the left. It’s a complicated picture because in some places labor is primarily supporting incumbents and in other they’re switching to supporting challengers. It’s hard to say where things are going, but certainly the union movement is very much in the mix right now in New York City and state politics.

Finally, what lessons have you held on to the most from the topics you’ve studied in you career as an educator and researcher?

I think the thing that I started and still believe in is the way ordinary folks can shape the world they live in, intervening in history and playing a critical role in shaping what’s around them and what future direction society’s going to go. And that’s a complicated story because the circumstances in which they do that is always changing and it’s often difficult to predict what lies just around the corner. So I have no doubt working people will continue to play a role in shaping the society, but to what to degree and what form, it’s too hard to know. Social movements are kind of mysterious things and they have their own dynamics. But certainly over and over again in history, we have seen working people pursue efforts to improve their own lives but do so in solidarity with others, and in the course of doing that they reshape the world.

Freeman’s most recent book, “Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World” was published in 2018.