Beneath the Planet of the Apes by Michael Avallone

In which the end of the world is accidental.

“Nova sagged against the stone circular side of the fountain, goggling at Brent with mingled terror and amazement. Brent fought himself not to approach her. The war in his mind was still raging. Kill her. Don’t kill her. He shook his head like a confused dog, fighting the outer pressures that wanted to push him towards her, destruction-bound.”

THE MOVIE

Whatever the flaws of Beneath the Planet of the Apes — and there are a lot of them — you can say this for it: it’s certainly surprising. Quickly green-lit by an ailing studio scrambling to cash in on the first film’s completely unexpected success, it looks cheap, runs short, and only features Charlton Heston in what amounts to little more than a cameo role, performed under sufferance and guilt-tripping from producer Arthur P. Jacobs.

For the rest of the runtime, Heston is replaced by a lookalike playing a character-alike: James Franciscus as Brent, another astronaut who has followed the trajectory of Heston’s Taylor in another dart-ship, and has to go through the motions of learning what Taylor learned last time and therefore we, the audience, already know. Taylor has disappeared in the Forbidden Zone. Brent runs into Taylor’s hot cavegirl squeeze Nova (Linda Harrison). Nova takes Brent to meet sympathetic chimp couple Zira and Cornelius (Kim Novak and, in Roddy McDowell’s absence, David Watson), and “My God, it’s a city of apes!” and etcetera.

So far so retread until, having escaped from the gorilla troops of General Ursus twice (both times with the help of Zira and Cornelius), Brent and Nova fall down a hole into the New York subway and discover a subterranean society of bald, telepathic fallout mutants worshipping a leftover nuclear bomb in the ruins of St Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. In the cathedral’s famous cells (errr…) Brent and Nova regroup with the imprisoned Taylor. Then the gorillas, on a Forbidden Zone warpath and on Brent’s trail, attack the undercity, everyone gets shot, and the dying Taylor sets off the doomsday weapon and destroys the entire world.

So, yes, the ending’s a bit of a downer.

Journeyman Ted Post (Hang ’Em High, Magnum Force) was the director. The screenwriter was Paul Dehn, who had most famously adapted Ian Fleming’s Bond novel Goldfinger for the screen, and whose WWII service had given him fervently held anti-nuclear sensibilities. Associate Producer Mort Abrahams also gets a story credit. Abrahams and Dehn’s original ending, which involved the birth of a half-human-half-ape boy, was vetoed early on. Armageddon by atomic holocaust was fine, but ape-human miscegenation was deemed to be going a bit far.

THE NOVELIZATION

You can abandon all hope of the novel doing anything to fix the film’s shortcomings. This is a straight-up retelling of what happens on screen, with only very minor deviations. Legend has it that the author Michael Avallone knocked this out in a single weekend. That may well have been self-promoting spin from a prolific writer deeply proud of his own hackery (see below), but given the quality of the work produced, it’s not impossible. The book has the same sort of stream-of-consciousness mania as the film, and it doesn’t seem like an editor played a large role (to be fair, there probably wasn’t time, whether or not the weekend story is literally true). The chapter headings, for example, are often character names, suggesting a single point-of-view, but it turns out to be pretty arbitrary. Sometimes — as with the “Ursus” chapter — it reflects the first time we encounter a character. But the “Nova” chapter doesn’t even have that going for it: it’s Brent’s POV, Nova isn’t central to the action, and we’ve been enjoying her company for 70 pages already.

In his defence though, Avallone doesn’t write down to the material: you don’t get the feeling that he feels it’s (ahem) beneath him. He doesn’t get any deeper into the aspects that very clearly mirror the Vietnam era — chimp peaceniks protesting in the streets and so on. He lays it all out there and moves swiftly on, perhaps reasoning like Post that momentum will paper over the cracks. But for the most part he seems to be taking it all reasonably seriously. He seems to note that the sudden, sombre voiceover at the end of the film is somewhat jarring, so at least takes the time to add that voice to a desolate prologue, bookending the narrative. We might, however, take the occasional line as a not-so-subtle wink at the reader. “Not even H.G. Wells at his wildest, not even Jules Verne, had dared conceive of a civilisation dedicated to the bomb,” he says at one point, as if raising a glass to Dehn. Or he could be raising an eyebrow, but he does seem kind of impressed.

There’s really nothing in the book that’s different to the movie until we reach the undercity, where we get a single brief sequence you could just about call a deleted scene. On screen, when Brent is led back out of the church and through the square with the fountain, we stay with the mutant priests as they watch him on their psychic projector cloud. The silent footage they see includes a group of children, seemingly dancing and then falling to the ground. In the screenplay and the novel, we stay with Brent and see this first-hand. The children are actually playing ring-a-rosey, substituting atomic lyrics in the same way as the barking mad cathedral choir we’ll endure later.

“Their squeals of pleasure sounded grotesque in the daylight… romping in a dancing circle, their voices gaily blending in a terrible refrain: Ring-a-ring o’neutrons / A pocket full of positrons / A fission! A fission! / We all fall down.” This is a straight lift by Dehn from his own poetry collection Quake Quake Quake: a grimly satirical “Leaden Treasury of English Verse” with typically deadpan illustrations by the great Edward Gorey.

There’s also a tiny moment during the bomb-worshipping ceremony, where the mutant Caspina gives Brent and Nova a look and sends a psychic message (unheard by us), to which Brent replies, “We can’t. We aren’t wearing masks.” Caspina is apparently offended that they haven’t, like the rest of the congregation, removed their faces for the service.

Otherwise, it’s just about small details. You might, like this writer, never have registered that the mutants make “the sign of the bomb”: a crossing-themselves gesture starting at the top and then moving downwards and outwards to represent the bomb’s tail fins. But it is there on screen, and Avallone makes pains to point out that it’s actually an inverted cross, “the supreme sacrilege”.

At one point Avallone likens the image of the gathered mutant priests to Rembrandt’s “Syndics of the Cloth Guild” (original title De Staalmeesters and more usually translated as “The “Sampling Officials” or “Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild”, but again, no editor in evidence here). It shows he’s, y’know, familiar with a painting, but it’s a bit of a stretch. Four of the six principal mutants are named in the script and the film’s closing credits (if not in the dialogue), but for some reason Victor Buono and Don Pedro Calley were only ever “The Fat Man” and “The Negro”. Avallone doesn’t bother to remedy that, so “Fat Man” and “Negro” they remain. And while Taylor gets an inner reverie sparked by Nova’s death, furiously picking over the early events of the first film, Avallone doesn’t even bother to look up the names of Taylor’s deceased shipmates. Stewart, Landon and Dodge, in Taylor’s own memory, become “the female astronaut” and “the others”.

Avallone is impressed by Heston, describing Taylor more than once as “massive”. But Taylor, when we meet him again in the cells, is shaggy and unshaven and wearing a “loincloth and tatters”, rather than clean shaven and wearing a peculiar white suit as we encounter him in the film. Heston, you might surmise, was damned if he was going full caveman and getting back into his previous shape just for a cameo in this thing.

And you’d also have to guess that Heston was responsible for the small but significant change to the film’s final moment. In the screenplay and the novel, Taylor’s already dead body falls on the console, accidentally launching the doomsday bomb. In the finished film, the dying Taylor deliberately sets everything off, his bloodied hand scrambling for and pulling on the mechanism. The previous film ended with “You blew it all up!” Beneath effectively ends with “I blew it all up!”

“Can the world exist half ape and half human?” asks the novelization’s front cover. Well, ultimately, no, we’re all dead. But thanks to Dehn’s tortuous continuity-ingenuity, the original Apes series continued through three more films, a TV series and a cartoon. Next time I deal with an Apes novelization here, it’ll probably be Battle.

Incidentally, there’s also a much more recent spin-off novel by Andrew Gaska, Death of the Planet of the Apes, which gets into what Taylor was up to all the time he was offscreen. Maybe I’ll get to that at some point too.

THE AUTHOR

Michael Avallone boasted that he was the author of more than a thousand novels, although so many were written under pseudonyms (of which he used at least 17) that the figure is impossible to verify. But he wrote at least 223 in his 74 years (he died in 1999), which is impressive enough. His main wheelhouse was crime, and he wrote 33 pulp detective stories about the wisecracking, hard boiled private eye Ed Noon alone. But he also wrote Westerns; he wrote horror novels; he wrote gothic romances; he wrote for children; he wrote everything, “to prove that a writer can write anything”. Along with Beneath the Planet of the Apes, his novelization work included The Man From UNCLE, The Girl From UNCLE, The Partridge Family, Hawaii Five–O, Krakatoa: East of Java, The Cannonball Run, Shock Corridor and Friday the 13th Part 3D. He also wrote for the Boris Karloff radio series Tales of the Frightened.

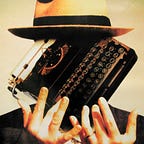

He lived in New York and New Jersey, dubbed himself “the fastest typewriter in the East”, and said he “never wrote a novel [he] didn’t like”. Others were less convinced (although the critic John Gross called him “a formidable figure”). Jack Adrian’s hilarious obituary in the Independent fondly records that “Despite his fecundity… Avallone had major problems with his raw material: words. Few writers… have committed more gross acts of grievous bodily harm upon the language of Milton [and] Shakespeare…” The critic Bill Pronzini said that, “out of all the bad writers of the century, [Avallone was] preeminently top of the heap — the Big Guy”.

About the Novelization Station project…

I’ve always had a soft spot for novelizations. As a kid, growing up pre-VHS, they were a way to re-experience films I’d enjoyed. In my early adolescence they became a way to “see” films that I wasn’t old enough to access. And into adulthood I continued to find them weirdly fascinating as warped, parallel universe versions of the things they were supposedly adapting: sometimes based on much earlier screenplays than the ones that were ultimately filmed, and sometimes crazily extrapolated and embellished by the authors themselves. They were — and still are — both hack work and a definite craft. My first major published magazine feature, more than a decade ago now, was an investigation of why they still exist when you can buy the DVD. In the age of Netflix, I still think that’s an interesting question.

They’re a niche interest and they’re not much studied, so my intention here is to create a platform to talk about them. I’m planning to publish one of these pieces every couple of weeks. I’m using the American spelling of “novelization” for SEO reasons and I will not be worrying about spoilers. Length and format of these pieces will vary, I think, depending on what there is to say. I’ve got my own list, but if there’s anything you’d like to see covered, give me a shout below the line or on Twitter.

Arriving next: The Gauntlet