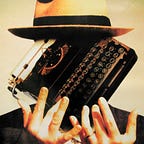

Dick Tracy by Max Allan Collins

In which a hardboiled hero is softened

I recently wrote this feature for The Telegraph marking the 30th anniversary of Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy. Part of the research for that was an interview with the great Max Allan Collins: custodian of the Dick Tracy comic strip for 15 years, an uncredited consultant on the film, and the author of its novelization. My Telegraph article quotes him a couple of times, but this is the full conversation, conducted by email over a couple of days in May, 2020.

A prolific writer of classically tough crime thrillers, Collins’ novel is tonally quite a lot “harder” than Beatty’s family-friendly onscreen adventure. But it turns out that there was, originally, an even tougher draft that the author was forced to scrap and start over. Having employed the hardboiled Collins, the producers were unhappy when he delivered a hardboiled Collins novel…

You were writing the comic strip at the time of the film, so when did you first start to hear rumblings that a film might happen?

The rumblings started very early — shortly after I took over writing the strip in late 1977, when the creator Chester Gould retired. (I was the writer. The artist was Chet’s assistant, Rick Fletcher, then later another assistant, Dick Locher.) I received a copy of the screenplay at least five years before the film went into serious pre-production. So much time had passed, I assumed what I’d read was something that had been rejected, because frankly I thought it was terrible, and was shocked when the shooting script was just a slightly later draft of what I’d first read.

You were a consultant on the film — what form did that consulting take, and who consulted you?

There were two stages to that. I don’t recall who contacted me first, but it was asking my advice on more villains from Gould that might be added, since they were having great fun devising the villains and their make-up. I gathered visual material and sent it along with info and guidance. Some of the ones I recommended made it into the film, though I can’t remember which ones.

The second stage had to do with the novelization. That was a hard-fought process, and in the final stages I was dealing with the producer, Barrie Osborne, who called me asking me why I had made certain changes. For example, in the script, Tess Trueheart’s mother encourages her to break up with her boyfriend, Dick Tracy, and disparages him. I made that less strident and I think made Mrs. Trueheart rather positive about Tracy. Mr. Osborne asked me why, and I said that Tracy joined the force to find Mrs. Trueheart’s husband’s killer — that this was Tracy’s origin and fans of the strip would read that as Hollywood disrespecting the property. There was a long silence, then… “Oh.” They rewrote that scene. At the premiere, Mr. Osborne told me that in the novelization I had solved problems they were having in the movie, ADR things, where they used my dialogue. I sometimes like to say I wrote the only novelization in Hollywood history that the movie was in part based on.

One funny thing — I was signing copies of the novel in a shop at DisneyWorld when we were there for the premiere. The actress who played Mrs. Trueheart, Estelle Parsons, came in and we chatted — I was and am a huge fan of hers, ever since Bonnie and Clyde. I said to her, about the Tracy film, “You had to re-shoot a scene, didn’t you? With new dialogue?” She looked astonished. “Yes! How did you know?” And I told her.

Did you have any meetings or dealings with Warren Beatty? Did he impress you?

I met him at the World Premiere at DisneyWorld. He was very nice and, not surprisingly, charming. He said flattering things about my work and said he would be calling me. Still waiting for that call. But I did send him my novel Neon Mirage, about Bugsy Siegel and Las Vegas…and the subject of that became his next film. Coincidence? Probably. In any event, you can’t copyright history.

Do you have a sense of why Beatty wanted to make the film?

I don’t know what childhood connection he had. My guess is that he liked the iconic value of this All-American character, and he had a vision for bringing a comic strip, in all its Sunday page glory, to the screen. And that is the great accomplishment of the film.

What did you think of the screenplay? How many versions did you see? How much did it change over the course of the production?

I thought it was terrible. I still do. But it served as a vehicle for Beatty to execute his vision, and the movie is wonderful, in its way. But it’s a beautifully restored classic car without an engine. The various versions of the screenplay that I saw were all very similar.

You’ve written several other movie novelizations — was the process on Dick Tracy any different to the others, given how close you were to the subject?

Dick Tracy was my first novelization, and I learned a lot, especially not to take liberties with the material unless given instructions to do so. I was, as you know, writing the strip and had been for thirteen years, so I had a proprietary attitude that made writing the novelization a kind of suicide mission. I wrote a novel very loosely based on the screenplay, fixing it in an admittedly arrogant way, putting in characters not in the script, doing my own death traps and strictly my own dialogue. I thought it was a terrific book and, in my memory at least, it still is.

But Disney rejected it, said they only read about a third of it and demanded I write a novel strictly faithful to the screenplay. I was given a very short deadline to do that — maybe two weeks, and during that two weeks my wife Barb and I were already going to Nassau on a research trip for my Nate Heller novel, Carnal Hours. I wound up writing on the plane and in the hotel room.

I was faithful to the screenplay, but still tried to fix things and I included characters and material that weren’t in the film, but nothing that contradicted the film. The tone of the book was not at all campy.

The big fight we had — and this went way to the top, including a phone call with Jeffrey Katzenberg — was my insistence that the identity of the Blank had to be revealed at the end. Otherwise I was writing a mystery novel that didn’t include the solution to the mystery. You will be astonished to learn that I lost the battle. I had a tiny victory in that the complete novel, ending and all, was published as a later printing, after the film was released. The studio people and Beatty and everybody thought they had this incredibly difficult-to-figure-out mystery, when almost everybody guessed it — many, probably in the opening credits.

How much access did you have to the production for reference? You thank Ed O’Ross in the acknowledgements for his “support” — was he sending you secret reports from the set??

That side of things was fantastic. I received tons of colour slides of shots taken on the set. Ed O’Ross played a villain, Itchy, and we got in touch somehow and he did feed me some info. Wonderful man and a terrific actor, too.

Do you still have your more radical original draft? I’ve been collecting that Hard Case Crime series that includes your Quarry books — I bet they’d jump at publishing your original Dick Tracy vision, rights permitting.

Funny you should ask, because I’ve been thinking of trying to find that version of the novelization, which is probably on a disc on an obsolete format, around here somewhere. I don’t know if I could get permission to publish it since it might involve Disney, the Tribune and even the screenwriters. I succeeded in getting DreamWorks to allow me to publish the full Road to Perdition novelization (I had been made to cut my 80,000 word novel, incorporating elements of the graphic novel, to something like 40,000, using only dialogue and scenes from the finished cut of the film).

I thought I might sneak the original Tracy novel out, as a sort of bonus feature to a reprint of the novelization, which might be possible to get the rights to do.

I left out one story. Barrie Osborne, very nice to me, scheduled a call with me about my final version of the novelization — he had notes. I had been through the wars on the book and was sickened by the thought of another round of changes. I braced myself for the call, expecting a laundry list of cuts — I had done a lot of subversive things, in bringing the characters around more closely to Gould. Then the changes required of me began: “On page twenty-seven…you mention a blue chair — it’s red in the picture. On page eighty, the hood is wearing a fedora — it’s a derby in the picture.” The cuts were all trees — the forest I’d planted didn’t get noticed. I managed not to laugh hysterically like Richard Widmark pushing the old lady down the stairs in Kiss of Death.

There were tie-in comics too, which you didn’t write. Was that just because they would have been too much extra to take on?

I was upset when I was not given the assignment of writing the comic book adaptation. (Glutton for punishment.) Later I heard that Beatty was so protective of his image that he was having every face redrawn over and over. Finally two or three okayed versions (three-quarter front, profile) were photocopied and used again and again, pasted in.

Were you surprised by the Batman-inspired scale of the marketing push? Could Dick Tracy ever have been another Batman?

The DisneyWorld premiere was a dizzying thing. I got to hang out with all the stars, at a Brown Derby party and doing press things. Dustin Hoffman was great to me — I told him I was doing a Mumbles story in the strip at the time, the character he played in the movie, and he found a newspaper with that day’s strip in it and read Mumbles’ dialogue aloud to me. That doesn’t happen to me here in Iowa every day.

Having written Batman myself, and knowing the depth of craziness attached to that franchise — both comics and films — I knew the Tracy film would not replicate Batman’s success. But I felt it would benefit from the positive climate toward comics on film that Batman generated. And the film was much, much better than I thought it would be. It’s one of those rare instances where a film vastly transcended its screenplay.

Were you happy with the film at the time? Did you agree with the more family-friendly approach or would you have preferred to see a more hardboiled version?

It’s a lot of fun. I loved it then and I love it now. The tone was correct. You can’t do a hardboiled Tracy on film. You can do it in the strip, particularly if you are a genius madman like Chester Gould. But it would be difficult if not impossible to capture that in a live action film. Of course, I feel that way about Batman, too, so it’s just possible I’m wrong.

Would Chester Gould have liked it?

He would have loved it. He was always frustrated that Tracy had only made it to the big screen in B movies. He wanted an A production, with an A star. Like Beatty.

And 30 years on, what are your feelings about it now? What do you think works, and what doesn’t? When did you last watch it?

I haven’t seen it in a while. I watched the Blu-ray when it came out. I still think it’s wonderful, and it has a timelessness that I think Beatty was striving for…and he hit it.

About the Novelization Station project…

I’ve always had a soft spot for novelizations. As a kid, growing up pre-VHS, they were a way to re-experience films I’d enjoyed. In my early adolescence they became a way to “see” films that I wasn’t old enough to access. And into adulthood I continued to find them weirdly fascinating as warped, parallel universe versions of the things they were supposedly adapting: sometimes based on much earlier screenplays than the ones that were ultimately filmed, and sometimes crazily extrapolated and embellished by the authors themselves. My first major published magazine feature, more than a decade ago now, was an investigation of why they still exist when you can buy the DVD. In the age of Netflix, I still think that’s an interesting question.