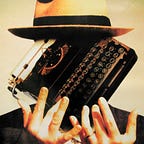

The Spy Who Loved Me by Christopher Wood

In which James Bond encounters Zbigniew Krycsiwiki.

“In Zbigniew’s swollen, brutish face and huge ungainly body, Stromberg saw a creature that might have come from the Stygian, unexplored depths of the ocean. He determined to recast him in the mould of his imagination.”

IAN FLEMING’S NOVEL AND THE 1977 MOVIE

The Spy Who Loved Me is the tenth James Bond film and the third to star Roger Moore. It shares its title with Ian Fleming’s novel from 1962, but otherwise goes entirely its own way.

In an act of morbidly fascinating authorial hubris, ultimate man’s man Fleming wrote the original book in first-person character as a nubile young Canadian protagonist called Vivienne Michel. “Viv” recounts her past journalistic career and romantic and sexual misadventures before hopping on a moped to the Adirondack Mountains and spending a night being terrorised by two gangsters in a motel. Bond only shows up by happenstance two-thirds of the way into the novel, and when it’s all over she gratefully falls into bed with him despite having been under the constant threat of sexual violence for the last several hours.

Following a critical drubbing, Fleming dryly called it an experiment that went “very much awry”. He asked for it to be taken out of print, which didn’t exactly happen, but a paperback version was withheld until after his death in 1964. The motel section was adapted for the Bond comic strip serial in the Daily Express between 1967 and 1968 (which bolted an unrelated new plot about SPECTRE and a top secret spy plane onto the beginning), but the contract Fleming had signed with Eon Productions forbade any elements of the novel being used on screen. The book’s only faint echo in the 1977 film is the borderline-parodic henchman character Jaws (played by Richard Kiel), whose deadly metal grillwork recalls the “glint of grey silvery metal from the front teeth… cheaply capped with steel” of Fleming’s thug Sol “Horror” Horowitz.

The film is boilerplate Bond but also arguably the best of the Moore era: a considerable achievement given a development dogged by bankruptcies and copyright disagreements. Several writers took a crack at the screenplay — Kingsley Amis and John Landis among them — before production went ahead with Christopher Wood’s draft. Lewis Gilbert (previously responsible for the rather similar You Only Live Twice) directed.

The story that reached the screen centres on the megalomaniac Karl Stromberg (Curd Jürgens, credited as “Curt”), who is kidnapping atomic submarines in order to drastically heat up the Cold War. His goal is to end the surface world so that he can start a new civilisation under the sea. Bond is forced into an unusual detente with beguiling Soviet agent Anya Amasova (Barbara Bach) to avert armageddon. Antics ensue, mostly in Egypt and Sardinia. This is the one with the submersible Lotus Esprit.

THE NOVELIZATION

This was the first original post-Fleming Bond novel to be published since Kingsley Amis’ patchy Colonel Sun a decade earlier. Its proper title is James Bond, the Spy Who Loved Me, to differentiate it from Fleming’s. Christopher Wood was here adapting his own screenplay, meaning that the omissions and additions are specific, deliberate decisions, rather than accidents of draft and production schedule. As a Bond aficionado he opted to undertake the novel as a Fleming pastiche. In that regard he’s hamstrung to some extent by distinctly un-Flemingian aspects like the submarine car, but for the most part it’s quite an admirable, witty job. Amis applauded him in the New Statesman for “bravely tackling the formidable task… of turning a typical late Bond film, which must be basically facetious, into a novel after Ian Fleming, which must be basically serious”.

This Bond is not Roger Moore, but “the handsome, cruel-faced man with the arrogant manner,” who smokes Morlands from a gunmetal case, has a “treasured Scottish housekeeper” called May, enjoys breakfast the best of all the day’s meals, and so on. Most of the quips and innuendos are gone (“All those feathers and he still couldn’t fly” alone survives the cut). Some lines are practically note-perfect Fleming: “Women you pick up in casinos are either straightforward whores or have run out of money playing some ridiculous system.” But occasionally Wood lapses into something more like fan fiction: “So you found Q’s gadgets useful, did you James?” asks M at one point.

The book begins slightly earlier than the film, with a preamble to Bond’s being in that snow-bound chalet. He’s in Chamonix for some rest and recuperation. There’s a none-more-Bond casino scene (“Bond loved gambling because to him tension was a form of relaxation”) where he picks up the seductive Martine Blanchaud. She and Bond head for her log cabin and some off-piste skiing on the Aiguille du Midi, accessible only by dangerous helicopter ascent, but it’s all a Russian sting operation. Bond doesn’t leave because England needs him, but because he twigs that something’s up after finding some suspicious tracks and another girl dead in a cupboard. But the ski-jump with the Union Jack parachute is intact, and Wood adds the fun detail of an old man shading his eyes against the sun and watching in amazement from the town far below. “‘Il sont fous, les anglais,’ he said, not without a trace of grudging admiration…”

Blanchaud is ultimately revealed to have been an agent of SMERSH: the Soviet counterintelligence organisation that provided Fleming’s books with regular antagonists up until Goldfinger in 1959, after which he started using SPECTRE instead. SMERSH (from Směrť Špionam: “death to spies”) was rarely mentioned in the film series, and on screen in The Spy Who Loved Me the Russians are KGB. In print, Wood opts for the Fleming version, adding a layer of extra tension to Bond’s reluctant pairing with Major Anya Amasova. If we take Wood’s novelization to be following the chronology of the novels, Bond has been tortured and almost killed by SMERSH several times by this point. Par for that course, in a scene that doesn’t appear in the film, Wood has Bond, after the murder of Fekkesh at the Pyramids, knocked unconscious, taken by SMERSH agents and aggressively interrogated. Anya puts a stop to his ordeal, unintentionally allowing him to kill the two men and escape.

Anya takes her SMERSH orders not from the film series’ twinkly General Gogol (entirely absent here), but from clammy sex pest Colonel-General Nikitin. Rather than Gogol’s sympathy for the loss of her lover Sergei (one of the Chamonix hit-men), Nikitin slyly chastises her for having probably been the erotic distraction that got Sergei killed. We’re given Anya’s record of achievement, including her most recent posting at SMERSH sex college (“lectures, films, demonstrations, and… ‘controlled participation’”), which she says was “very interesting”, much to Nikitin’s lascivious fascination. Wood, much like Nikitin, is extremely taken with Anya’s breasts. Bond likes looking at them “poking through her shirt”. At one point we get half a long paragraph about her rubbing suntan lotion into them. They’re described in forensic detail: her nipples a “rich, chocolate brown… [jutting] out like plump, juicy antennae.” Martine Blanchaud’s, meanwhile, were “white as snow”.

Wood gives us SMERSH but he was unable to give us SPECTRE. Early drafts of the screenplay by other writers involved Fleming’s terror organisation, and the villain would have been a returning Ernst Stavro Blofeld until Kevin McClory objected. Instead, we get Karl Stromberg, although Wood changes his first name to Sigmund.

On screen we learn little about Stromberg, but the prose version tells us he has been a collector of deadly fish since childhood. After the not-unsuspicious deaths of first his parents and later an aunt and uncle, he inherited the family mortuary business, and turned his “unmeasurable” IQ towards world domination: amassing his fortune first through bizarre high-society cremations, then a fleet of supertankers, and ultimately a crime industry to rival the Cosa Nostra.

Marine biology appears to be merely a hobby, but one he excels at as he does at everything else. But he has a physical connection to his favoured subject. In a detail that’s present in the film but very easy to miss, Stromberg’s hands are webbed. Wood retains this, and adds that, when Stromberg is angry, “he would suck in his lips so that his mouth disappeared into his face to be replaced with a tiny dimple like a baby’s umbilicus. His skin would turn a deathly white and his eyes suddenly fill with red as if the blood drained from his cheeks had rushed to fill their sockets. At the same time he would wrap his arms around himself and shake in silent, inchoate rage.” Doctor No had metal pincers and a heart in the wrong place. Stromberg is a mad toad pufferfish-man. He and Bond shake hands, as they explicitly don’t in the film. Bond notes the hand’s “corpse-like coldness”.

And then there is Jaws, and you wonder if Wood was drinking heavily when he wrote these pages. Stromberg’s massive adjunct, we learn, has another name. It is Zbigniew Krycsiwiki, and he is Polish: the son of a circus strong-man and the chief wardress of a women’s prison. In his youth his height led him to basketball, but his monstrous physique made him “sluggish” and he became renowned as a freak and a dirty player that the crowds loved to hate. His career ended when he beat a referee to death with a hoop. He went on to work as a slaughterhouse butcher. His jaw was destroyed in a merciless truncheoning by secret police during “the 1972 bread riots” (he got arrested for tearing up and throwing paving slabs), but after stowing away on a Stromberg ship in Gdansk and catching the boss’s eye, he was taken on and given the steel choppers we know and love by the ex-Buchenwald surgeon Ludwig Schwenk (who had previously “grafted an Alsation’s head to a man’s body and kept the resulting mutation alive for three weeks.”) Schwenk works for Stromberg because Stromberg has a thing going blackmailing Nazi war-criminals by threatening to reveal their whereabouts to Mossad.

Those metal dentures are actually part of an entire cyborg jaw: “Zbigniew’s vocal chords had to be severed and re-harnessed to the electric impulse conductor that opened and shut the two rows of terrifying, razor sharp teeth.” This is why Jaws is mute, “like a fish”. He also has “tiny pig eyes”. And he loves Anya; Stromberg plans to mate the two of them.

Elements that are in the film but missing from Wood’s novel include the entire opening sequence where the submarine is swallowed by the supertanker; the scene on the train where Jaws is hiding in a wardrobe; and the part in Egypt where Bond meets his old Cambridge pal Sheikh Hosein in a Bedouin tent and has a go on his harem. There’s no “shared bodily warmth” seduction scene on the boat after Bond and Anya’s escape from Jaws: Anya knocks Bond out in the van as they drive away (with a needle, not a trick cigarette). And there’s no Q. Fleming’s books occasionally mention Q-Branch and Major Boothroyd, but the character played by Desmond Llewellyn is more-or-less an invention of the film series. Presumably for that reason, Wood excises him completely. The info-dump about tracking submarines by their wake is paraphrased by M, and the examination of the microfilm is handled by a technician called Belling. We don’t see Bond taking delivery of the Lotus, although in describing it to Anya he does use Q’s famous line from Goldfinger, “with modifications”. In a callback to the “Little Nellie” gyrocopter in the film of You Only Live Twice, we learn that the Lotus submarine is called “Wet Nellie”. As much as he’s writing “as” Fleming, Wood cheerfully throws in movie references whenever it amuses him. It’s all part of Bond’s rich pageant.

There’s no Naomi either. Bond and Anya are simply boated out to Stromberg’s “Atlantis” base (not named as such here) by generic goons rather than Caroline Munro’s character, and she’s replaced in the helicopter during the chase sequence by Jaws. The latter is therefore not in a car, so we don’t get the part where he swerves his Ford Taunus off a cliff and into the roof of a shack, only to wander out of its front door shortly afterwards, brushing himself off. In the context of the novel, even with all the Jaws madness intact, that might have been a slapstick moment too far. The helicopter isn’t destroyed.

We don’t get the moment where Anya is detailing Bond’s life story and hits a wall when she mentions Tracy (Bond’s wife, killed at the end of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service). But we do get her saying “we have all the time in the world” without knowing its significance, and Bond being quietly upset about it. During the climactic battle, Stromberg gets the drop on Bond but is crushed accidentally by a sliding table in the tumult of the rig’s collapse. And Bond and Anya make it to the escape pod, but the scene ends as the craft shoots away from the rig and Bond collapses into unconsciousness. There’s no moment with M and Gogol (or Nikitin) meeting them at the shore, and nothing about Bond “keeping the British end up”.

We finish with a new epilogue at Bond’s Chelsea flat. He enjoys eggs, bacon, toast, butter and marmalade (Cooper’s Vintage Oxford) and “two, large, strong, unsweetened cups of black coffee” courtesy of May. Carter the American submarine captain comes to visit him to say thanks before he heads back to the States, and then Anya shows up to help with Bond’s convalescence. When he asks about Russia she says she’s on holiday but will explain more later: the suggestion being that she’s either been relieved of duty or defected. Her breasts “curved towards Bond invitingly”…

THE AUTHOR

Christopher Wood’s obsession with Anya’s rack makes perfect sense in the context of the rest of his career. He got the Bond gig through prior work with director Lewis Gilbert on Seven Nights in Japan, but he was best known and enjoyed his greatest success as the author of the Confessions series of novels and films, and as the creator of Rosie Dixon: Night Nurse and its successors (Gym Mistress etc.). He disliked the term “soft porn”, and preferred to think of himself as an enthusiast and peddler of thoroughly British “smut”.

Away from ’70s sexploitation, his — often pseudonymous — pulp fiction also included historical adventures, WWII action, and horror. After The Spy Who Loved Me he wrote the screenplay and novelization of its immediate follow-up Moonraker, as well as Remo Williams: The Adventure Begins and a couple of Roger Corman films. His final book was a brief memoir, James Bond: The Spy I Loved. He died in 2015.

About the Novelization Station project…

I’ve always had a soft spot for novelizations. As a kid, growing up pre-VHS, they were a way to re-experience films I’d enjoyed. As I got a bit older they became a way to “see” films that I wasn’t old enough to access. And into adulthood I continued to find them weirdly fascinating as warped, parallel universe versions of the things they were supposedly adapting: sometimes based on much earlier screenplays than the ones that were ultimately filmed, and sometimes crazily extrapolated and embellished by the authors themselves. They were — and still are — both hack work and a definite craft. My first major published magazine feature, more than a decade ago now, was an investigation of why they still exist when you can buy the DVD. In the age of Netflix, I still think that’s an interesting question.

They’re a niche interest and they’re not much studied, so my intention here is to create a platform to talk about them. I’m planning to focus on one book a week. I’m using the American spelling of “novelization” for SEO reasons, and I will not be worrying about spoilers. Length and format of these pieces will vary, I think, depending on what there is to say. I’ve got my own list, but if there’s anything you’d like to see covered, give me a shout below the line or on Twitter and I’ll very likely oblige.

Arriving next: Predator