Transcending Polarity

Developing Trust and Relationships

Citizens of the USA are more polarized today than ever since the Civil War. This polarization includes political, religious, ethnic, nationality, and social status conflicts. Thus, many persons can be seen as presenting some threat or danger to us and our worldview. That is a major challenge that we have to deal with one way or another — it is a choice — every day.

The necessary element to even begin bridging the gap is TRUST. We distrust anyone who we perceive to be a potential threat to our safety, well-being, livelihood, or peace of mind.

Trusting another person involves knowing something about the other and believing that they are safe to be close enough to interact with them, even when we disagree with or dislike them. This personal interaction is in a deep sense learning more about the other and testing their trustworthiness.

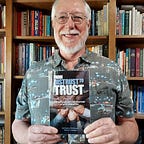

In our book, From Distrust to Trust, we addressed how this polarization has affected faith communities.[1]

We also included a couple of “how to” chapters on communication that apply to any human group. These include the Trust-Building Cycle that facilitates the overcoming of the barriers that divide us (p. 81–9).

The four aspects of our trust-building process involve learning how to communicate to connect with the hope of having a productive, civil conversation that can lead to increased understanding.

When we listen to understand the other, we learn about others’ values and how the topic affects them. This increased understanding can lead to increased peaceful interaction. This article briefly describes what works to transcend divisive polarity between persons with different statuses, orientations, cultural backgrounds, and/or opinions.

What is your fundamental attitude toward those who are different?

The term alterity or otherness is founded on the existence of pervasive diversity and plurality — there are inevitable differences between individuals and cultural groups of people. Each is most familiar and comfortable (settled?) in their self — their own judgments — based on their personal experiences and their cultural group. This results in feeling uncomfortable, leery, and distrusting of those who are not like us.

Tolerance and accepting some basic differences are a necessary part of developing a relationship.

The cycle of trust-building includes humility, hospitality, relationality, and intersectionality.

Each of the aspects of developing trust will be addressed separately although they are not mutually exclusive categories and not necessarily happening in a linear sequence as is used here for simplification.

Humility requires tolerance of alterity with an attitude of openness — Dweck’s growth mindset — to connect with unfamiliar people. [2]

It is the personal quality of experiencing what Virginia Satir referred to as “peace within” — knowing that one’s self is no better than nor worse than any other person.[3]

Humility negates any perceived social power differential and is essential for equality and equity to exist. And, is a prerequisite for inclusion.

For some, accomplishing humility presents a great challenge. However, it is simply being aware of personal limitations as well as strengths and not feeling a need to compete with others for status. Thus, humility is being authentic — knowing and accepting one’s true self. It also requires being vulnerable and taking risks by being transparent, which is sharing one’s true, authentic, or mature self with another.

All you have to do is be yourself and let the other be who they are.

Vulnerability and risk-taking are necessary parts of developing trust in a relationship. As more time is spent doing this while interacting with the other, trust can be increased to the point of loyalty and reliance on each other and working collaboratively for the common good as is elaborated in the next section.

Hospitality involves not only acceptance but also spending time engaging with the other despite differences to establish Satir’s “peace between” the two persons.

Actions expressing the attitude of welcoming and including are required to further the trust in a relationship.

Enacting hospitality requires the intentional inviting of the other to be included in activities. When that happens, persons can continue dialoguing to become better acquainted and proceed with building trust. The epitome of this is sharing personal space in routine activities such as eating or drinking together. Thus, demonstrating the accomplishment of belonging together.

There are challenges in this trust-building phase as hospitality needs to include no intention of changing the other person to be more like us. It is accepting and welcoming the other — just as they are.

Once we have established equity in the relationship, through mutual sharing, cooperation, and serving, then the trusting relationship can continue to relationality — the next phase in building trust.

Relationality is “peace among” alterity.

By having empathy for understanding the other and truly caring about and affirming each other, relationality can develop. Thus, it demonstrates a feeling of safety in the relationship — the reward for risk-taking — despite differences that may remain. This is the stuff that friendships are made of.

Relationality involves not only some shared acceptance and understanding but can also include shared passions and purposes in collaborating on a common goal, which may be simply socializing. When we have engaging empathy and intentional compassion that enables us to work together as mutual friends, then the relationship can progress to intersectionality.

Intersectionality is the final phase of the trust-building cycle.

Intersectionality requires accurately knowing and understanding the other person in totality — the whole person. It is based on the premise of hybridity.

Hybridity means each of us has multiple categories of our identities or identifying characteristics that make our whole person. We share some aspects of our person with others but we also have some differences — some of which are unique. It is the totality of one’s life history: interactions and changes that have taken place — good or bad.

Intersectionality includes the individual’s life experiences, which have occurred at a certain time in a certain place in a certain culture within a certain socio-political structure. Thus, it includes historical and cultural elements, which the Germans call zeitgeist. Conceptually, it means we are recognizing and accepting that individuals have multiple intersecting and simultaneously overlapping social identities indicative of the complexity of diverse life experiences, which may differ greatly from one’s own.

All of the life experiences, and the different aspects of the individual intersect in that person in the moment. Thus, their personhood is exhibited from that intersectionality in the now.

The concept of intersectionality is a disruptive innovation that enables an expanded view and understanding of all aspects of the person as they truly are, including experiences of privilege, power, injustice, or trauma. Characteristics such as gender, socio-economic status, ability level, race, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, gender identity, or religion can be empowering or oppressing.

The term was coined by law professor, Kimberle Crenshaw.[4]

She represented female, minority auto plant workers before the U.S. Supreme Court. They had not been allowed to apply for supervisory positions because they did not have the required years of experience. However, the high court was made aware that the plant had not allowed any BIPOC workers or any female team leaders early enough to meet their requirements for a supervisory position. Thus, Crenshaw won the case for the minority women, which enabled them to become supervisors.

The application of the intersectionality concept to identity arose from the reality that everyone has multiple features that intersect within their personhood. For example, one individual in a functioning relationship is female, Christian, white, LGBTQ+, and impoverished. The other person in the relationship may be male, Black, highly educated, agnostic, straight, and middle-class.

All of those different identifying elements intersect within the person resulting in multiple and various ways they may be labeled, categorized by stereotypes, and discriminated against or honored.

Intersectionality is necessary for mutual understanding, acceptance, and collaboration. It affirms differences among persons and scrutinizes how power is deployed, which can help leaders imagine and create new ways to equity and justice.

Power and accompanying privileges must be shared in a way that feels good, beneficial, and safe to the other. By embracing intersectionality one becomes willing to share authority with those who have definite differences — even those living in the margins — as they work together as equals.

Completing the cycle of trust-building means that all can feel not only safe but also secure and confident in trusting and joining in activities without debilitating fear or anxiety.

Thus, we are back to the place of feeling shared peace, gratitude, and humility, which enables and empowers us to be strong enough to be vulnerable and take the risks of opening our hearts and talking to those who are different from us even when our gut feels uneasy.

Those actions help to share space and build trust by embracing alterity, inviting, and welcoming all to join in working for the common good — “all” meaning all.

By completing all of these four phases or paths of building trust, we invite, welcome, include, support, and affirm others to work collaboratively in our communities. This includes those who live in the margins, those who are different — even minority persons who are lower on the power-differential scale, as well as the privileged on the higher end.

By accomplishing peace within, peace between, and peace among, we can continue this cycle perpetually for peace and harmony with the divine.

[1] Matthew B. Sturtevant and Timothy J. Bonner, From Distrust to Trust: Controversies and Conversations in Faith Communities, Judson Press, 2023.

[2] Carol S. Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Random House, 2006.

[3] Virginia Satir, J. Banmen, J. Gerber, and M. Gomori, The Satir Model: Family Therapy and Beyond, Science and Behavior Books, 1991, p 8.

[4] Kimberle Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (1991): 1241–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.