How to build an interdisciplinary collaboration for social justice

CODEC’s research projects are based on Victor Papanek’s thought: “The only important thing about design is how it relates to people.”

Background

In 2014 I was sitting on the terrace of a pub in Budapest across from my business partner, one of the co-founders of our company. It was one of those already cool afternoons when you understand that the summer is over. We were drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. “I don’t think there is a way back” — he said. “Well, I guess so then” — I replied, not being able to express in words my feelings about how disappointed, angry, exhausted and guilty I felt at the same time about the situation.

We started Hello Wood from scratch almost by accident. Originally organised by Søren Lindgreen, the Copenhagen International Wood Festival had been cancelled. We had applied to the National Culture Fund of Hungary for some money to organise the festival in Hungary and got 10% of our budget. At almost the same time I met an old friend who was working for JAF Holz, a wood company as PR manager. So we had 4km of construction timber, 20 participants and a venue. The first event was organised in 2010 and was low-budget, exciting and fun. Today Hello Wood is an award-winning international architecture programme and a design studio based in Budapest. Every year 100+ students from around the word meet for one week to build huge wooden installations.

In 2014 I sold my share of the company. Different visions for Hello Wood meant selling my share to my co-founders was the only option at that time. I’m still amused at how banal the reasons of our split were. Lack of communication and unmanaged expectations. That’s it. The first lesson in any business/management course, nevertheless.

Why am I telling this story? Since that time I find myself obsessed with the phenomenon of collaboration. It seems so obvious and such a natural thing to do, while actually quite complicated. The balance of a group dynamic can be very fragile.

After one and a half years I was lucky enough to find new friends and partners in the endeavour called CODEC, the Co-Design Collaborative.

The main idea behind CODEC is that there are many freelancers and micro-companies who are geographically distributed across Europe and the world and willing to work on big scale / high impact and meaningful / socially and environmentally positive projects. Bringing these forces together might make a difference. But how do you do that? What’s the best way to start and operate this kind of network of collaboration, cooperation? Before getting too deep, I want to make sure that I’ve done my homework and can avoid meaningless tension as in case of Hello Wood. This time my approach is more scientific. The idea is to look into the available knowledge, exploring best practice cases, talking to people and posing questions.

I’ve been lucky enough to find people like Barbara, Kate, Michala and Henryk (see appendix 6:3) who are willing to dedicate their time and attention to this exciting experiment.

This report is part of a series we are working on in gathering knowledge we think will help us set up CODEC in the best possible way. Beside this primary aim we hope to share this knowledge with others who seek to start similar endeavours.

Problem statememt

There is nothing new about the idea of bringing people and organisations together. Many businesses are facing the challenge of scale and questions on how to deliver quality assured services from flexible resources. These challenges are especially great when the service involves innovation and high-value intellectual performance.

One solution is to build a network and use its capacity, which of course opens another set of challenges. Many corporations are in constant search for cooperation and collaboration opportunities. Following the Collaborative Innovation Report by the World Economic Forum, collaboration is one of the most important features of competitiveness named by senior managers and at the same time it is something that needs the most improvement. The research also shows that there is a lack of advanced knowledge on how to set up and operate a collaborative network. (World Economic Forum, 2015)

Many grants, like the EU funds or the International Visegrad Fund, seek to foster collaboration. The main idea is connecting actors from different countries to work on diverse topics and projects. But many funded projects fail (based on my own experience) to continue after the funding period is over, some of the projects fail to deliver a real impact. The reason being that receiving funding is the primary aim for this kind of cooperation and not a tool.

On the other hand, you see lot of grassroots initiatives that try collaborations but fail to secure a long term continuity. Most of the time they lack the funding, a relevant business model and/or an efficient collaboration model to maintain the network.

Nevertheless, collaboration is a natural solution when it comes to dealing with challenges such as scaling, innovation, and change. But networks fail to operate efficiently and effectively. There must be a gap in knowledge on how to set up and operate collaboration (or more precisely interdisciplinary collaboratives or collaborative networks). So the quest of my research is a search for an evidence based model that makes collaboration work.

Research topic

I have a vision. A vision of a mostly self-governed, effective and efficient, competitive but at the same time healthy and happy organization, which works on projects which have value for the environment, society and users/clients (in that particular order). I know this sounds like naive wishful thinking. And I agree that this is an ambitious goal. Nevertheless, I firmly believe that it is worth trying to achieve it. Trying and learning never hurts. Or as Buckminster Fuller once said, “you can never learn less, you can only learn more.”

Thus, my research topic was a simple one: how can we build and operate a collaborative organisation or network? Where to start? What questions to ask? What tools to use?

Objectives and methods

The objectives of this research were to gather knowledge about collaborative networks and to identify what kind of practices can operate in a collaborative environment. The ultimate goal was to collect information on what works, what doesn’t and why. The scope of this research didn’t allow me to collect and analyse all existing sources and existing practices but it does show a path to further investigation. The idea is to continue this research and to allow iteration periods to test the gained knowledge. CODEC has, and will, serve as a laboratory for experiments in innovation research, using the knowledge gathered from the aforementioned researched topics.

The methods chosen for this research were: examining secondary (printed and online) sources, collecting data via interviews (qualitative method) and gathering knowledge on the topic through workshops.

Literature review

In a literature review several topics were covered. Topics from collaborative networks, innovation, management, business models, strategic design, behaviour science.

Reflective practice

It is also important to stress the need for personal conversations and workshops. Both can have enormous power. In this report I will also use the outcomes of the second CODEC workshop, which was conducted in the spring of 2017 by the co-founders of the Co-Design Collaborative network.

Phenomenological approach

Interviews with freelancers and collaborative network practitioners helped me gather the needed insights. The phenomenon of design focused interdisciplinary collaborative networks is not yet understood, therefore to understand and interpret the experience of people who work in such collaborations on everyday basis was crucial for the research. During this research I interviewed 15 people. You can see a list of interviewees along with a short bio in Appendix 6:2.

Lifelong learning

This research shouldn’t be perceived as a finished piece. We will continue to experiment with new models of research, topics and relations. The aim is to build flexible tool with a room for constant improvement. All research outcomes will be regularly published on our website: codec.network.

CONTEXT

Section Two will present how I came to the conclusion that interdisciplinary collaborative networks are something we need to investigate and experiment with. I believe that by explaining my line of thought, it will be easier to pinpoint if I’m mistaken or missing something, or if I’m right, thus improving conditions of collaboration.

Key factors

Meaningful

First things first. Let’s get it over now, so it doesn’t stay in the way. We are all aware that currently there is a lot of hype for being meaningful, making the word a better place. Nowadays you cannot start a start-up without the aim of saving the world or better yet the whole universe. I agree with the positive impact of being conscientious about the outcomes of your decisions and having noble aims to support social and environmental justice. Even so, I get the feeling that in a lot of cases “being meaningful” and “making a world a better place” are just buzz words with no real intent, no real action or possible effect behind them. Words become overused slogans, thus I will try to avoid using them.

Why gives the meaning

So why collaborative networks? Why interdisciplinarity? I find myself in agreement with Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle theory (Sinek, 2009; Fig. 1). One of the most important questions to answer, whether you start a new business, a social purpose organisation or — I would argue — even research, is “the why question”.

So, following the advice from Sinek I will explain the need to focus on collaborative networks, what pushes me forward to focus on interdisciplinary collaboration and what has design got to do with all of this.

As I stated at the beginning, it all started with a lack of purpose, or better yet, with a misfit of individual and organisational purposes. After successful years with Hello Wood I started to realise that I was lacking the impact Hello Wood promised to deliver on social issues. We hosted students from around the word, we had enormous fun, we went to various regions to figure out how we could channel the energy and enthusiasm into something socially and environmentally positive. But at the end of the day, the result of the workshops was just huge wooden installations, students having fun and some commercial gigs. Not underestimating these achievements, but I still missed the aforementioned social and environmental positive impact.

At the time I was curious about the complexity of our word. I thought and still think that we are living in a world of hyper-connectivity, hyper rapid changes and hyper-complexity. This setting is a hotbed for wicked problems that were brilliantly described by C. West Churchman (1967) and later by Horst W. J. Rittel and Melvin M. Webber in the context of design (1973). We are talking about a class of social system problems which are ill-formulated, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values, and where the ramifications in the whole system are thoroughly confusing (Churchman, 1967). To solve such problems is extremely difficult because of the complex interdependencies, the effort to solve one aspect of a wicked problem may reveal or create other problems.

Partly based on my visit to the International Design Business Management program at Aalto University in Helsinki, and partly based on my own experience at the MOME line, the design agency of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, I came to the conclusion that answers to escalating economic and social wicked problems can only be a complex comprehensive solution. Or to say it more accurately: comprehensive resolutions, due to the fact that: “Social problems are never solved. At best they are only re-solved — over and over again.” (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 160)

We have to improve our processes, services, and products to make positive changes in our society and environment. In other words we need to innovate. Innovation is another worn out expression, used and misused almost as much as the word “meaningful”. We need to create new net value through implementing ideas for improvement. (Richards, 2014) And we don’t need the kind of innovation which brings more problems than solutions. (Russel and Vinsel, 2016) Due to the fact that I am coming from the design field I started to investigate the connection between innovation and design. I was curious about the role of design, if any, in the innovation process, which might bring a positive social and environmental change.

It is widely acknowledged that design can add value to the innovation processes in the business and public sector (see: Chiva and Alegre, 2009; Dell’Era and Verganti, 2007; Design Council, 2015; Martin, 2009) even on strategic level (Hill, 2012; Holsten, 2011; Holland and Lam, 2014; Stevens, 2010). Still I am sceptical about the hype that design is the solution for everything. (Similarly as it was and still is the case with technology.) In my opinion, design is (and should be) just one of the disciplines in solving or resolving complex, wicked problems. It is important to stress that design is not a panacea. It has some undeniable advantages, such as being human cantered and as a result — via prototyping and testing ideas at an early stage — can avoid huge mistakes. Design is without doubt the best tool when it comes to usability and desirability, but it lags behind in many cases when it comes to feasibility and viability. Laura Weiss’ diagram (Fig. 2) nicely shows how the intersection of business, technology and design can bring better innovation outcomes (Weiss, 2002).

Social innovation

Building on Weiss’ diagram, an innovation process which wants to deal with wicked problems should have at least two more aspects. Namely, social and environmental factors. Taking social and environmental factors into consideration while working on any product or service will bring social and environmental justice. These aspects are crucial if we want to deal with wicked problems in the long run. Another crucial aspect which can’t be left out is culture. Developing any kind of solution as a service or product and not considering the cultural aspects of the given society is almost a sure way to fail. The combination of all five factors inside the cultural milieu builds the model I call the pentagon model of social innovation (Fig. 3):

Interdisciplinarity

The pentagon model leads us to the insight that another key to successful social innovation is interdisciplinarity (Blackwell et al., 2010; Payne 2014; Barrett et al., 2011). Innovation carried out by interdisciplinary teams can lead to complex and comprehensive solutions and can solve or at least resolve wicked problems.

What do I mean by interdisciplinarity? It’s a team where each team member brings different expertise in order to solve a problem. This kind of interdisciplinary collaboration can lead to new kinds of knowledge and crosses the boundaries by which knowledge is structured. It is important to distinguish interdisciplinary from multidisciplinary teams. Counter to multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity has an impact on all disciplines involved in the process. Or as described by Nesta’s research, it is creating value across boundaries (Blackwell et al., 2010).

Managing interdisciplinary teams

What remains unanswered is, how do you organize, lead and manage interdisciplinary innovation teams?

One solution would be to establish an interdisciplinary team in every organisation. This is clearly not a feasible approach. Since each project needs different types of expertise, coming from various disciplines, all depending on the nature of the problem, it would be enormously expensive to have a team representing every possible profession.

A more feasible approach would be to organise an interdisciplinary team for every project. This sounds better but it has its problems as well. The setting up requires a lot of time and energy, there is no organisational learning, the team members are not familiar with each other and the process of collaboration and all of the above might lead to poor performance.

The answer, in my opinion, lies with an interdisciplinary collaborative network. A network of individuals who represent different professions, can easily form interdisciplinary innovation teams. At the same time the individuals are part of a network or collaborative connected by shared values, purpose and experiences maintaining the culture of collaboration, knowledge sharing and governed by rules and rituals everybody accepts.

Scholars agree that such networks provide proper answers to wicked, complex problems (Isett et al., 2011) and are a nurturing environment for innovation activity (Hoberecht et al., 2011; Thorgren, Wincent, and Örtqvist, 2009/9; Gloor, 2006).

Before diving into the possible scenarios and existing examples of such networks, let’s look at some theories and research outcomes in the field of network and collaboration. Most of the used sources are from the public sector (mainly from the healthcare industry) and some also from the business sector without the intention “making the word a better place”.

Network

“In very broad terms, networks are defined by the enduring exchange relations established between organizations, individuals, and groups.” – Edward P. Weber, Anne M. Khademian (2008, p. 334)

A typical reason for forming a network is that there are synergies between the members. It is important that a network is more than just a sum of the members (Provan and Kenis 2008). There are obvious potential benefits of being part of a network, such as access to resources, knowledge, complementary skills and capacities, flexibility and responsiveness, which allow each member to focus on its core competencies while keeping a high level of agility. “In addition to agility, the new organizational forms also induce innovation, and thus creation of new value, by confrontation of ideas and practices, combination of resources and technologies, and creation of synergies.” (Camarinha-Matos and Afsarmanesh, 2006)

Here is the overview of the network classifications based on different aspects:

1) Level of cooperation, collaboration

Obviously in any networked environment the members have to conduct some level of cooperation, collaboration. “A process in which entities share information, resources and responsibilities to jointly plan, implement, and evaluate a program of activities to achieve a common goal.” (Ibid., p. 3)

Based on the intensity of collaboration or integration level Camarintha-Matos et al. similar to Huerta et al. research (2006) distinguish four types of networks (Fig. 4):

a) Network: involves communication and information exchange for mutual benefit.

b) Coordinated Network: members (beside networking) also align and adjust their activities in order to maximize their impact.

c) Cooperative Network: involves sharing resources and labour on top of coordination. A traditional supply chain is a classic example of such cooperation.

d) Collaborative Network: is the most integrated level of networking.

Based on the research of Huerta et al. we can say that regressing from a pure network towards the collaborative network sees the activities of the network members transform from pure exploration (transmission of low risk information) towards pure exploitation (working together). (Huerta, Casebeer and Vanderplaat, 2006)

2) Purpose of the network

To dive even deeper into networks, Popp et al. (2014) creates network categories based on their purpose (the primary aim, objectives and actions of the network):

Information sharing, informational, information diffusion

Primary focus is on sharing information across organizational boundaries. A number of authors make a distinction between information sharing and knowledge exchange.

Knowledge generation and exchange, knowledge management

Primary focus is the generation of new knowledge, as well as the spread of new ideas and practice.

Capacity building, social capital, outreach

Primary focus is on building social capital in community settings, and on improving the administrative capacity of the network members.

Individual, organizational, network and community learning

Primary focus here is learning, which overlaps both with knowledge exchange and capacity building.

Problem solving, complex issue management

Primary focus is on improving response to complex issues, and/or solving complex problems (where a solution is possible). Often emerges from an information diffusion or knowledge exchange network.

Effective service delivery, service implementation, service coordination, action

Primary focus is service delivery, where services are jointly produced by more than two organizations.

Innovation

Primary focus is on creating an environment where diversity, collaboration and openness are promoted with the goal of enabling and diffusing innovation.

Policy

Primary focus here is an interest in public decisions within a particular area of policy. The original conceptualization of policy networks concerned decision making about public resource allocation.

Collaborative governance

Primary focus on direction, control and coordination of collective action between government agencies and non-public groups, including government funded initiatives or contracts. (Popp et al., 2014)

Of course, there is no active network that would pursue only one purpose of the above listed purposes. Rather, each network is a unique mixture of the described purposes.

To better understand network dynamics we have to understand what the benefits and what the challenges of being a member of a network are. Any system will function only if the former outweighs the latter.

Benefits of the network

According to Popp et al. these are the most common benefits of being part of a network:

Broader set of resources

Access to resources not held within a particular organization.

Increased capacity

Capacity to deliver services for a higher demand.

Innovation

Networks are enabling structures that create opportunities for innovation.

Flexibility and responsiveness

Capacity to be more flexible and responsive in order to deal with changing demand and unforeseen problems.

Learning, knowledge exchange

Knowledge exchange enables learning. (Popp et al. 2014)

It is important to stress that these categories reflect a managerial point of view of the benefits and misses the human factor. The latter is nevertheless introduced by many recent collaborative network practices. As Richard Bartlett, member of the Enspiral network states in his interview answering my question, why are people part of the Enspiral network, it is in his opinion

“because of the feeling of belonging.”

(From the interview with Barlett, personal archive, 2017)

Challenges of the network

But there is no gain without pain. “Cross-sector collaborations, although a promising mechanism for addressing issues that are complex and interconnecting, are no panacea, and can create as well as solve problems.” (Popp et al. 2014) Challenges which occur by working in a collaborative network are: achieving consensus, loss of autonomy, coordination fatigue and costs, management complexity, power imbalance. All mentioned can result in conflict. Again, let’s have a look at the factors causing tensions in a network presented by Popp et al.:

Varied commitment to network purpose and goals

Members come with diverging perspectives and priorities, varying levels of trust.

Culture clash (especially in interdisciplinary networks)

Members have different ways of doing things (decision making, ways of providing services, transparency, methodology, quality). This makes it challenging to agree on essential structures, processes and outcomes.

Coordination fatigue and costs

Working collaboratively and coordinating decisions and activities take time and effort away from the day-to-day work. As well, it is not uncommon for a single member to belong to multiple networks, which exacerbates the time and effort required.

Developing trusting relationships

Trusting relationships take time to build, and must continue to be attended to if trust is to be maintained over time because reciprocity emerges from repeated interactions.

Management complexity

Management within a network context requires managing across members as well as within the traditional hierarchical structures. (Popp et al., 2014)

Factors

As we can see working in networks can be challenging. In order to address them, there are factors which should be designed cautiously to build an effective and efficient collaborative network. I believe there is an art of setting up well functioning collaborative networks which requires a combination of leadership, (eco)system engineering, design, management and communication skills.

There is a natural overlap between factors, but it’s worth to have a look at them separately as it might help us to understand better the nature of each one. To do this, I will use the Community Canvas as the basis for my analysis and complement it insights from my interviews and other resources.

The Community Canvas distinguishes 3 sections of concern for community design. These are seen as different colours on the figure 5: identity (blue), experience (red) and structure (green). Each section is divided into several themes, 17 altogether.

The Identity section (blue)

The identity of a community and as such of a collaborative network is the core component. Without a clear identity, it is hard to build a network. It can be done, but in this case, other aspects should outweigh the lack of identity. The identity section is divided into 5 themes. All of them defining the identity of the community.

As mentioned before, the most important part is the purpose of the network. It defines grounds for the members of the network and what they hope to achieve. We have to distinguish between two types of purpose. The internal purpose addresses the notion of belonging, on the idea of learning from each other, helping each other. The external purpose has to do with the world around the network (for instance “making the word a better place”). It is worth to stress the obvious: in order to achieve a good group dynamic, the purpose of the network should be aligned with the purposes of its members as much as possible.

Below the purpose is identity (named a bit misleadingly) and is the second most important aspect of any organisation. My suggestion is to call it simply “people”. The professional and collaborative skills of the people who are part of it, will define the whole network. It seems an obvious insight, but nevertheless, it is important to emphasise that organisations are not part of any network, but people are (even when they represent an organisation). This means that the whole structure of the network should be designed around people and not organisations. “Communities are always ‘for’ someone — a group of previously disconnected people who share one or several commonalities: a shared identity.” (Community Canvas)

To recap, in order to build a successful collaborative network, we will need personal skills and an environment that supports collaboration. To put it differently, we will need collaborative skills. Collaborative skills are behaviours that help two or more people work together and function well in the process. Basic collaborative skills are very similar to communication skills. These are:

· ability to join in

· commit yourself to working with others

· listening what others have to say

· encourage others to speak up

· speak for yourself, if you have an idea or opinion

· know how to effectively begin and end a conversation

· know how to ask for help or favour

· know how to follow directions, manuals

· ask questions when confused or curious

· effectively express your feelings as well as concerned for others

· have a grasp of basic manners

· know how to say no without offending others

· ability to give a compliment or constructive criticism

· know how to accept a compliment or constructive criticism

· posses skills for negotiation: a need to discuss a disagreement until you can come to an agreement

When it comes to people, diversity is an issue that needs special attention. The diversity of any network provides the interdisciplinarity needed for successful social innovation. “We have found mature communities to be intentional about the diversity of their members. Most communities gain significant strength and value from a more diverse pool of members (as long as they still retain their commonalities and shared identity). However, diversity often doesn’t happen naturally or easily. Strong communities design their selection processes with diversity in mind, but a true dedication to diversity goes further: making sure that a diverse group of people actually feels comfortable and welcome in the community, and creating event formats and rituals that speak to the strengths of all types of members. Ideally, diversity is an integral part of all aspects of the organization.” (Ibid.)

There are some methods that can help you to determine the personalities of your members which is useful if you aim to set up a diverse team. These are the Co-Lab test at the 100% Open (www.100open.com/colab-test), IDEO’s ten faces of innovation (Littman and Kelley, 2005) or the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (Myers, 2010).

The third part of the Identity section is values. Values provides the common ground in defining how members treat each other, work together, on what kind of projects they collaborate and on which they don’t. A shared set of values is a powerful management (or even better said non-management) tool which allows flat, self-organising structures. It also brings decision processes as close to the problem or task as possible.

The next important factor to consider is success definition. Success definition provides grounds for easier communication of the overall goals of the network and thus helps to engage the members in collaboration over longer periods of time.

Brand also helps in uniting the members of a network. A strong brand (supported by a strong purpose and things to be done) makes the members proud and helps them communicate their network to the world. For instance, the most valuable asset of the OuiShare community is their brand, which helps open many doors for their members.

The experience section (red)

This section is about answering the questions; what happens in the network? and how does it create value for the members?

The selection process of the members is crucial for any network. As mentioned in the identity section, the people in the network define its quality. A selection process can be open (anyone can join) or closed. Based on the conducted interviews, a selection process based on invitation or referral is the most common. Besides the selection process, on-boarding is another factor that helps build well-functioning networks. Successful networks know how to make new members feel welcome: by clarifying the structure and processes of the network. The transition process on the other hand deals with the steps, rules and experience of leaving the network.

“From the perspective of a member, the shared experiences are what makes up the core of the community. These experiences lead to more interactions which lead to more trust among the members. More than specific formats, we have found that rhythm and a reliable sense of repeatability play a huge part in making shared experiences more effective. Consistency gives members a sense of safety and signals to them that the community and the relationships are something to invest in for the longer term.” (Community Canvas)

Other forms of shared experience are rituals and traditions. Both have a primarily symbolic value and can be very personal. The knowledge, insights and stories created through these shared experiences generates content which again helps to shape members’ experience and bring them closer together. Trust is the lubricant that makes cooperation and relationships between actors (individuals and organizations) possible. In general, higher levels of trust are believed to lead to more effective collaboration (Axelrod, 1984). Behavioural science is the field addressing these issues. The specific subfield is called exchange theory — it investigates how different forms of exchange (negotiated and reciprocal exchange) influence the level of trust. (Cropanzano, Mitchell, 2005)

Another useful tool to manage expectations is a well-defined set of roles. This way the commitments and expectations of members can be managed, etiquette and accountability can be clarified.

The structure (green)

This section is about the leadership, management and organisational aspects of the network.

An organisation needs leadership and management. The structure and the incentives of those define how a network functions.

The governance models regulate the decision making, power and conflict handling. Although the models below are quite old and mainly deal with networks of organisations, it is nevertheless worth taking a closer look at Provan and Kenis (2008) network governance types (see also Fig. 6):

· Self-governed networks

Networks without lead organization. Cooperative interactions must be legitimized by the members of organisation themselves, typically through the gradual process of trust building. Due to the fact that members of self-governed networks have no other organization they can rely on, they are the ones that need to build the interactions by themselves and legitimized them. If they don’t do it, then no network will exist. (Ibid., pp. 131–132)

· Lead organization networks

A network of multiple organization networks with a single entity doing the coordination and integrating on behalf of the entire network. While the role of this lead organization in a cooperative network must be legitimized by participants for the network to succeed, its legitimacy is often already established, both through its size and control of resources, and through its prior relations with network members. (Ibid., p. 127)

· Network administrative organizations (NAO)

An alternative governance mechanism is for the network to be coordinated and managed by a separate legal entity set up specifically for that purpose (with its own administrative staff, executive director, and governing board). The NAO structure is especially common among networks that are not dominated by a powerful lead organisation (examples are less frequent in business than in the public and non-profit sectors). (Ibid., p. 128)

The next level (if there is an evolution intent in this model) is again a self-governed network, but better organised. As we will see in almost all of the present best practice case studies I will introduce later on, some sort of self-governed, self-organised governance model is in practice.

The question of governance brings us to leadership and management. According to Provan and Kenis (2008), Huxham and Vangen (2013), Keast et al. (2004), Provan and Lemaire (2012) challenges described in previous paragraphs can be overcome by effective leadership and management. But they are all missing the point by not taking into consideration emerging management theories and practices. A close investigation of new approaches such as sociocracy (www.sociocracy.info), management 3.0 (Appelo, 2010) and holacracy (www.holacracy.org) brings new perspectives to network management models. These are perspectives that cannot be overlooked.

What are then, the key characteristics for good leadership and management of the network?

· No heavy, centrally directed control;

· Balance between providing direction and letting things emerge;

· Establish a foundation upon which network participants can operate;

· Transparent rules and policies;

· Flexible;

· Honest;

· Role of the leader is more of a facilitator, broker:

- treating all network members equal,

- freely sharing information amongst members, and

- creating trust amongst members. (Popp et al., 2014)

Even more, following June Holley notions written in Network Weaving Handbook (2012), four leadership roles are identified for network weavers:

· Connector catalyst: connecting people and helping to get the network started;

· Project coordinator: helping network members with their self-organized projects of interest;

· Network facilitator: helping with ongoing development of network structures, activities and relationships; and

· Network guardian: putting in place systems such as communications, training and resources to help the network as a whole function effectively.

On the other hand, Wheatley and Frieze (2011) clarify that leaders-as-hosts do not just benevolently let go and trust that people will do good work entirely on their own. In part because people are often used to being told what to do and consequently, as they indicate, there is a great deal of work for hosting leaders to do in shaping the conditions for a successful outcome, including:

· Providing good conditions and group processes for people to work collaboratively;

· Creating opportunities for people and the network to learn from experience;

· Keeping the bureaucracy(s) at bay by creating enclaves where people are less encumbered by bureaucratic requirements;

· Playing defence with network participants who may be used to playing a more traditional leadership role, and who want to take control;

· Reflecting back to network participants on a regular basis what they are accomplishing and how far they have come;

· Working with people to develop relevant measures of progress in order to make achievements visible; and

· Valuing true esprit de corps, the spirit that arises in any group that accomplishes challenging work together.

To conclude this chapter, let’s briefly stop at financing, channels and platforms, and knowledge exchange. Financing is often an overlooked aspect of most networks. More on this topic can be found in CODEC’s research paper New Business Models for Collaborative Networks, written by Henryk Stawicki (2017).

Channels and platforms describes the modes of how the network members communicate. “We have found that while a clear understanding of the channels and platforms is important, what matters even more is rhythm and consistency. It matters less how the community communicates and what is communicated, as long as communication happens regularly in a reliable manner.” (Community Canvas)

Last but not least are the fields of data management and knowledge exchange. Both help any network evolve and mature. More on the topic was researched by Justyna Turek and Michaela Mydlová and is published in CODEC’s research paper Knowledge Exchange in Collaborative Networks (2017).

CASE STUDIES

The following case studies were investigated to deliver additional qualitative data. As mentioned in Section Two, selected best practices are all built on some sort of next level self-governed, self-organised governance model.

Enspiral

https://enspiral.com/

Location: Wellington, New Zealand

Enspiral is a virtual and physical network of companies and professionals working together to create a thriving society. The main idea of the Enspiral Network is building a network for social enterprise ventures and social entrepreneurs in order to work together with shared vision and values.

Relevant findings

− The network provides a platform for people working on stuff that matters. The founders believe that powerful things take place when like-minded people connect. That is why the main value of the network is belonging. Being connected as member of a really deeply committed, actively and mutually supportive tribe. This is a fundamental need everyone has.

− Collaborative decision-making is based on autonomy, transparency, diversity, entrepreneurialism and non-hierarchy. Diverse perspectives come together to make decisions online (loomio.org), enabling shared understanding and collective action.

− Collaborative Funding: projects to support the network and its vision are funded using a transparent participatory budgeting process.

− Enspiral practice 5 levels of engagement:

· Foundation — Collectively owned by the members

· Foundation Members — Invite ventures, contributors, and new members

· Contributors — Involved in decision-making and collaboration

· Friends & Partners — Wider ecosystem of supporters

· Enspiral Network — Community of people and ventures

So far the best self-management model for organising the members is forming small 5–6 people teams who are working together, are legally responsible as a team and are intimately aware of each other. These small teams are part of a wider community of around 250 people and share the same culture, assumptions, values, behaviours and language.

OuiShare

ouishare.net

Location: Paris, France

OuiShare (an experiment of collaborative organization, a permanent beta project) is a global community empowering citizens, public institutions and companies to build a society based on openness, collaboration and sharing. A non-profit organisation was founded in January 2012 in Paris, OuiShare has rapidly evolved from a handful of enthusiasts to a global community spread across Europe, North, Latin America and the Middle East. The community is powered by a network of so called OuiShare Connectors who lead projects and activities. Its main hubs are in Paris, Barcelona, London, Munich, Montreal and Rio. Being dislocated might have its own challenges or as Franceska Pick (member of OuiShare) put it: “The big challenge for being distributed is that sometimes you don’t even see if people are disengaged. Sometimes people disengage and leave and you don’t even know why that happened.”

Relevant findings

− OuiShare connects people and accelerates projects for systemic change. They experiment with social models based on collaboration, openness, and fairness. Most people are freelancers or have their own company. Ouishare is a place where they get their gigs. Each project is autonomous and people connect based on projects.

− The main challenge is to build an organization that can grow organically through distributed leadership and self-organization, while staying aligned with a common vision and the interests of the community. The idea is to evolve and change with each new individual that joins and the project they work on.

− Along with self-organization they propagate the idea of do-ocracy, which means that decision making is based on actions and on the concept of stigmergy[1]. It is important to stress that every community develops its own governance model. The local summits are about shaping this governance. The global summits are about sharing these local models and discussing what works and what doesn’t.

− Individuals can have 3 levels of involvement within OuiShare. They are Members, Connectors or Friends.

· Members are individuals who identify themselves with the OuiShare mission, values and culture, and actively contribute to community activities, such as events, projects or online discussions.

· Connectors are the highly active members that put the mission into action day by day. They are community and project leaders who participate in the creation of the OuiShare strategy and take part in decision-making processes.

· Friends: support the idea, talk about it, spread the news and are interested in their activities

− Funding: due to the fact that OuiShare is a non-profit organization, all of their work is shared openly. To cover the costs of operational and strategic activities, OuiShare draws from following sources of funding:

· Sponsorships and ticket sales (mostly for events);

· Public grants and subsidies;

· Global Partners, who are forward-looking organizations that support OuiShare on an annual basis;

· Donations from individuals.

Or as Franceska Pick said: “When you pay someone for something that should be in the DNA of the organisation then you might decrease the level of this activity since people will think if there is someone who is paid to do that I don’t have to do that.”

Mozfest

https://mozillafestival.org

Location: London, UK

The world’s leading festival for the open Internet movement. MozFest is the annual celebration of Mozilla community with the aim to build a greater open Internet movement. Each year, a diverse group of experts gathers together to discuss, debate, create and hack in oreder to build a better Internet. The curation of the Festival is a collaborative effort. Around 40 people work on the content. Everything they do is transparent and accessible by anyone.

Relevant findings

− Main goal: to ensure the Internet is a global public resource, open and accessible to all. Meaning, teaching web literacy to more people in more places. It also means asking hard questions about what an ‘inclusive Internet’ really means, and to actively address the challenges faced by people who don’t yet feel they are welcome on the Web.

− Due to the diversity of the participants, guidelines covering behaviour are necessary. In short these guidelines tackle:

· the necessity to be respectful and welcoming

· trying to understand different perspectives

· not threatening with violence

· empowering others

· striving for excellence

· not expecting to agree with every decision

− Core value: Working in the Open. The idea is to build the culture of transparency and collaboration during the Festival, and to continue with an open ethos in projects after Mozfest.

3.4: Project00

www.project00.cc/

Location: London, UK

Zero zero is a collaborative studio of architects, strategic designers, programmers, social scientists, economists and urban designers practicing design beyond its traditional borders. Building from a few individuals based out of Impact Hub Islington into a vibrant ecosystem of change makers now exploring a variety of exciting ideas. They operate an open business model.

Relevant findings

− Their main mission is the radical democratization of our cities. For instance: they are rethinking how to distribute power to empower society in a radical sense.

− Their work can be client based as well as their own investment in building the venture by themselves. On the other hand, they don’t like working with freelancers, due to the fact it enhances a consumer economy. If you hire them, you consume their capabilities on a transaction basis. You are not investing in the relationships because you’re both marginal to each other. That is why at Project00 are investing in people and that allows them to build a different type of culture.

− Organization: Project00 has been a holding company since 2004. Or as Indy Johar, architect and co-founder of Project00 stated: “I’m not sure we are a network. I think we are genuinely a research and development studio. Collaboratively owned. What happens is, when people build open-desk we incubate and structure it and then it spin-offs into a separate company. Project 00 is a place to build things from.”

RESEARCH RESULTS

In Section Four, we will once again see that the most important factor for collaborative networks to successfully operate is to have a common purpose, in order to direct the energy and actions of the members towards a common goal. To put it differently, the idea of the value systems (in sync with its members) must be perceived as a driver of the collaborative network. This is why mapping the value system of the members and participants of any collaborative network is one of the key necessary steps.

So why are we doing this?

Answering the why question defines our existence, the existence of CODEC. One of the most common adjectives that came up during our strategic workshop was … wait for it … meaningful. Yes, the same meaningful I mentioned as the first key factor in Section Two. This alone brings us closer to understanding what meaningful means for CODEC. Together with other raw (workshop) data captured on sticky notes on our wall in Prague (Fig. 7).

So what does it say on the sticky notes? (grouped into topics, in no particular order).

Aims:

· Purpose: form social, environmental (and cultural) groups

· Create real (social) impact

− Long-lasting outcomes (impact with measurable change: before and after)

− Creating positive change (responsible design)

− Hack a non-working system

− Solves a community (public) problem

− Opportunity to develop new method / knowledge / tool

− Opportunity to bring tools to a community in order to face / solve challenges

− Short term is fine as well

· Good energy

· Have chemistry with partners

· Professional quality

· Help to change the status quo of what design can do / Give design a new meaning, far away from styling

Ways of working:

· Local / Working with and for community (co-creation)

· Open in order to be continued by others

· Makers

· Human (and other spices) centered

· Make small steps towards new sustainable living (in the city for example)

· Social and environmental responsibility; health, balance, sustainability

· Future, critical, speculative thinking: think ahead to what kind of world we want to live in (and how to influence that)

· If we are facing radical changes -> what would be a sustainable solution

Who for:

· Not only for designers: but for and with trans/interdisciplinary teams

· Not for hipsters

· Opportunity to extend the network

· Not for profit:

− Not selling anything / Don’t want to make more things for the market

− Against supporting overconsumption

· Personal growth

In short: We all want to do something that we are proud of, that is lasting, that makes sense and that helps others. This motivation is a powerful and inspiring purpose.

LOOK AHEAD

Before we end, let’s come clean: the aim of the CODEC is (at least partly) to help solve wicked problems. We are at the very beginning of this journey. This research helped us (and hopefully will help all others who are thinking about their own collaborative network) to understand the challenges we are facing. It is also provides us with practices that are worth following and learning from.

At CODEC we strongly believe in the “learning by doing” approach. I even co-founded CODEC because I had a gut feeling for a long time that interdisciplinary collaboration is the right answer for current social, environmental and economic challenges. This organization will help me to carry on the reflective practice approach to understand the dynamics of design driven interdisciplinary innovation projects while working on them. And this research helps us with the direction CODEC should take regarding structure, leadership and management issues.

We are also certain that there are things we don’t understand and will need to be investigated further. Especially in the areas of behavioural science and psychology, from the perspective of group dynamics and motivation. How to engage more thoroughly is something I would like to personally look into further.

Besides the knowledge we gathered during all five research projects, one of the most valuable outcomes is the CODEC network itself. People who are part of CODEC can call each other friends and can count on each other’s generosity in collaborating and supporting the further development of CODEC. We are grateful for the generous support of the International Visegrad Fund that made all of the above happen.

Appendix

6.1: References

Appelo, Jurgen (2010): Management 3.0: Leading Agile Developers, Developing Agile Leaders, Pearson Education.

Barrett, Michael; Velu, Chander; Kohli, Rajiv; Torsten, Oliver and Simoes-Brown, David (2011): Making the transition to collaborative innovation, Nesta. www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/making_the_transition.pdf (May 28, 2017).

Blackwell, Alan; Wilson, Lee; Boulton, Charles and Knell, John (2010): Creating value across boundaries. Maximising the return from interdisciplinary innovation (research report), Nesta, www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/creating_value_across_boundaries.pdf (May 28, 2017).

Camarinha-Matos, M. Luis; Afsarmanesh, Hamideh (2006): “Collaborative Networks Value creation in a knowledge society”, Proceedings of Prolamat 2006, IFIP Int. Conf. On Knowledge Enterprise — New Challenges (January 2006).

Chiva, Ricardo; Alegre, Joaquín (2009): “Investment in design and firm performance: The mediating role of design management”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26, pp. 424–440. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2009.00669.x/full

Churchman, C. West (December 1967): “Wicked Problems”, Management Science, 14(4). http://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/pdf/10.1287/mnsc.14.4.B141 (May 28, 2017).

Community Canvas: https://community-canvas.org (May 25, 2017).

Cropanzano, Russell; Mitchell, Marie S. (2005): “Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review”, Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900, www.researchgate.net/profile/Russell_Cropanzano/publication/234021447_Social_Exchange_Theory_An_Interdisciplinary_Review/links/0f317533f27818077b000000/Social-Exchange-Theory-An-Interdisciplinary-Review.pdf (June 5, 2017).

Dell’Era, Claudio; Verganti, Roberto (2007): “Strategies of innovation and imitation of product languages”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 25, pp. 580–599. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2007.00273.x/full (May 28, 2017).

Design Council (2015): The Design Economy executive summary, www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/The%20Design%20Economy%20executive%20summary_0.pdf (May 28, 2017).

Gloor, Peter A. (2006): Swarm Creativity: Competitive Advantage through Collaborative Innovation Networks, Oxford University Press.

Hill, Dan (2012): Dark matter and trojan horses: A strategic design vocabulary, Strelka Institute, Moscow.

Hoberecht, Susan; Joseph, Brett; Spencer, Jan; Southern, Nancy (2011): “Inter-organizational networks”, OD and Sustainability, 43(4), p. 23. http://ecologicalculture.org/documents/Inter-organizationalnetworks-AnEmergingParadigmofWholeSystemsChange.pdf#page=25 (May 28, 2017).

Holland, Ray; Lam, Busayawan (2014): Managing Strategic Design, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Holley, June (2012): Network weaver handbook: A guide to transformational networks. Athens, OH: Network Weaver Publishing.

Holsten, David (2011): “The Strategic Designer”, Cincinnati: How Books.

Huerta, Timotht R.; Casebeer, Ann; VanderPlaat, Madine (2006): “Using networks to enhance health services delivery: perspectives, paradoxes and propositions”, HealthcarePapers, 7(2), pp. 10–26.

Huxham, Chris; Vangen, Siv Evy (2013): Managing to Collaborate. The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage, Taylor & Francis.

Isett, Kimberley R; Mergel, Ines A; LeRoux, Kelly; Mischen, Pamela A; Rethemeyer, R Karl (2011): “Networks in public administration scholarship: Understanding where we are and where we need to go”, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(1), pp. i157–i173, www.academia.edu/download/39727512/Isett_et_al_2011_Networks_in_PA.pdf (May 28, 2017).

Keast, Robyn; Mandell, Myrna P; Brown, Kerry; Woolcock, Geoffrey (20014): “Network structures: Working differently and changing expectations”, Public Adm. Rev., 64(3), pp. 363–371. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00380.x/full (May 28, 2017).

Kelley, Tom; Littman, Jonathan (2005): The ten faces of innovation. IDEO’s Strategies for Beating the Devil’s Advocate Driving Creativity throughout Your Organization, Currency/Doubleday.

Martin, Roger (2009): The design of business, Harvard Business School Publishing, Massachusetts. http://xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/16596003/1941655930/name/design-of-business-martin-e.pdf (May 28, 2017).

Milward, H. Brinton; Provan, Keith G. (2006): A Manager’s Guide to Choosing and Using Collaborative Networks Networks and Partnerships Series, IBM Center for the Business of Government, pp. 6–28. http://www.srpc.ca/ess2016/summit/Reference_9-Milner.pdf (May 5, 2017).

Isabel Myers, P. M. (2010). Gifts Differing: Understanding Personality Type. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1525/jung.1.1981.2.3.18 (June 5, 2017).

Payne, Mark (2014): How to Kill a Unicorn: How the World’s Hottest Innovation Factory Builds Bold Ideas That Make It to Market, Crown Publishing Group.

Popp, J., Milward, H., MacKean, G., Casebeer, A. and Lindstrom, R. (2014): Inter-organizational networks: A review of the literature to inform practice, Collaborating Across Boundaries Series, IBM Center for the Business of Governmen, www.businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/Inter-Organizational%20Networks_0.pdf (May 15, 2017).

Provan, Keith G.; Kenis, Patrick (2008): “Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness”, Journal of public administration research and theory, 18(2), pp. 229–252. https://pure.uvt.nl/ws/files/964494/modes.pdf (May 28, 2017).

Provan, Keith G.; Kenis, Patrick; Human, Sherrie E. (2008): “Legitimacy building in organizational networks” in Lisa Blomgren Bingham and Rosemary O’Leary, Big Ideas in Collaborative Public Management, Routledge.

Provan, Keith G; Lemaire, Robin H. (2012): “Core Concepts and Key Ideas for Understanding Public Sector Organizational Networks: Using Research to Inform Scholarship and Practice”, Public Adm. Rev., 72(5), pp. 638–648. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02595.x/full (May 28, 2017).

Richards, Dave (2014): The Seven Sins of Innovation. Environmental Claims in Consumer Markets, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137432537 (June 5, 2017).

Rittel, Horst W. J. and Webber, M. M. (1973): “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning”, Policy Sciences, 4(2), pp. 155–169. www.cc.gatech.edu/fac/ellendo/rittel/rittel-dilemma.pdf (May 28, 2017).

Russell, Andrew; Vinsel, Lee (2016): “Innovation is overvalued. Maintenance often matters more”, Aeon. Retrieved from https://aeon.co/essays/innovation-is-overvalued-maintenance-often-matters-more (June 5, 2017).

Sinek, Simon (2009): “Start with why: how great leaders inspire everyone to take action”, Portfolio the Magazine of the Fine Arts, pp. 1–7.

Stevens, J. S. (2010): Design as a Strategic Resource: Design’s Contributions to Competitive Advantage Aligned with Strategy Models, University of Cambridge.

Thorgren, Sara; Wincent, Joakim; Örtqvist, Daniel (2009): “Designing interorganizational networks for innovation: An empirical examination of network configuration, formation and governance”, J. Eng. Tech. Manage., 26(3), pp. 148–166.

Wheatley, Margaret; with Frieze, Debbie (2011): “Leadership in the age of complexity: From hero to host”, Resurgence Magazine, 264, 14–17. www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/Leadership-in-Age-of-Complexity.pdf (June 15, 2017).

Weber, Edward P; Khademian, Anne M. (2008): “Wicked Problems, Knowledge Challenges, and Collaborative Capacity Builders in Network Settings”, Public Adm. Rev., 68(2), pp. 334–349.

Weiss, Laura (2002): “Developing Tangible Strategies”, Design Management Journal, 13(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1948-7169.2002.tb00296.x (June 8, 2017).

World Economic Forum (2015): Collaborative Innovation Transforming Business, Driving Growth, www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Collaborative_Innovation_report_2015.pdf (May 28, 2017).

6.2: List of people interviewed (in alphabetic order)

Sarah Allen is Executive Director of MozFest. Sarah draws her experience from a diverse events background having worked with creative and inspiring companies such as Movember Europe, Secret Cinema and CSM iLUKA.

Megan Anderson is design researcher at STBY and a PhD candidate at Leiden University. Her research explores how public sector organisations design and improve new and existing services and is funded by a Marie Sklowdowska-Curie actions grant, as part of a wider European Union FP7 project. Megan is a passionate advocate for the use of service design and design research within the public sector.

Richard D. Bartlett is one of the cofounders of Loomio, an open source software tool for collective decision-making. He’s also a member of Enspiral: a decentralised network of people using the tools of business to pursue radical social change. His background is in creative activism and DIY electronics. He’s passionate about co-ownership, self-management, collaborative governance, and other ways of sneaking anarchism into respectable places.

Jasmine Cox is a Designer & Producer in the Future Experiences team in R&D. She’s usually based in the North Lab. With a background in Product Design, Jasmine has expertise across electronic, industrial, and mechanical design. She crafts playful interactive experiences, devices, and control systems — embedded into the web.

Lauren Currie is a European designer and entrepreneur from Scotland. She lives in London and spends her time as Head of Design at Good Lab and founder of #upfront. She makes, thinks, writes and speaks about confidence, design, and social change. She co-founded Snook, one of the UK’s leading service design and social innovation agencies which uses design to make services better. Management Today recently named Lauren as one of the UK’s top 35 business women under 35. She designed and led Hyper Island’s new MA in Experience Design and was recently featured in ELLE UK as 30 women under 30 changing the world.

Sonja Dahl: since joining Nesta, Sonja has been instrumental in designing new partnership projects and programmes with UK, European and worldwide clients. She also leads on a number of pan-European programmes including Design for Europe, which enables European countries to share learning on innovation methods and tools in the public and social sectors. Sonja drives a design-led innovation agenda across a range of initiatives in Nesta’s portfolio. Before joining Nesta, Sonja was Head of Design at the Design Council and was instrumental in the design and development of their Leadership Programmes for the public and private sectors.

Martyn Evans is a professor of Design, product designer and design academic with 20 years research, teaching and leadership experience and is Head of Manchester School of Art Research Centre. Interested in the strategic role that design commands in a variety of settings, his research explores the approaches designers use to conceptualise and communicate the future. With broad experience of design as future making, he has presented on this, and related, topics nationally and internationally. He is a reviewer for a number of research councils and was appointed as a strategic reviewer for the AHRC in 2017.

Roland Harwood co-founded 100%Open is coming from NESTA where he was Director of Open Innovation. Graduating with a PhD in physics from Edinburgh University, he has held senior innovation roles in the utilities and media industries and in addition has worked with 100’s of start-ups to raise venture capital and commercialise technology. In addition, he has worked as a TV and film music producer for SonyBMG.

Mat Hunter managing director of Central Research Laboratory. Mat’s career has focused on design-led innovation across a number of fields; firstly, at global innovation consultants IDEO, in both San Francisco and London, developing digital products, services and strategies, then as Chief Design Officer at the UK Design Council where he led pioneering work bringing design and start-up practice to public and non-profit sectors. He also established the Design Council Spark product investment fund accelerator.

Indy Johar is an architect, co-founder of 00 (project00.cc) and a Senior Innovation Associate with the Young Foundation and Visiting Professor at the University of Sheffield.

Indy, on behalf of 00, has co-founded multiple social ventures from Impact Hub Westminster to Impact Hub Birmingham and the HubLaunchpad Accelerator, along with working with large global multinationals and institutions to support their transition to a positive Systems Economy.

Richard Koeck is professor and chair in Architecture and the Visual Arts in the Liverpool School of Architecture, Director of the Centre for Architecture and the Visual Arts (CAVA). He is also Associate Head of the School of the Arts, where he leads Research and Impact for five departments. He holds a professional degree in Architecture from Germany and two postgraduate degrees from the University of Cambridge in Architecture and the Moving Image (M.Phil. and Ph.D). Richard is founding director of CineTecture Ltd., an award-winning video production company based in Liverpool.

Graham Leicester is director of the International Futures Forum. Graham previously ran Scotland’s leading think tank, the Scottish Council Foundation, founded in 1997. He has a strong interest in governance, innovation and education. He is a senior adviser to the British Council on those issues, and has previously worked with OECD, the World Bank Institute and other agencies on the themes of governance in a knowledge society and the governance of the long term.

Si Lumb is Senior Product Manager for BBC Research & Development, specialising in games technology and interactive format innovation. He works in the Connected Studio and User Experience team experimenting with new types of audience experiences and prototypes in the fields of virtual and augmented reality, new types of play and the use of games technology to enhance and expand the notion of modern broadcasting.

Francesca Pick is a collaboration catalyst, network pollinator, consultant and speaker that is interested in how tech can change business, society and human interaction. As a member of OuiShare and Enspiral, she explores new ways of working and governing collaboratively, with a focus on how to create agency in organizations through collaborative financial tools. She is an advocate for more collaboration, empathy and holistic thinking to address the challenges in our rapidly changing world.

Gill Wildman: from 2004 as co-founder and principal of the innovation consultancy Plot, Gill has designed and developed the interventions that Plot undertakes across industry sectors for clients such as Nokia, Microsoft, the BBC and Participle.

6.3: Research author and CODEC’s founding members

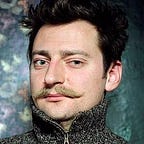

Maxim Dedushkov, principal Investigator and CODEC founding member

Maxim is a design expert and strategic designer. Maxim has been part of the design scene since 2008. He is the co-founder of Hello Wood, an international wood workshop and festival, founder of HOLIS, a holistic design summer university, founder of MOME line, the design agency of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, founder of MOME ID, a digital product course and the driving force behind the Budapest Design Meetup. He runs a small design agency called Dedushkov.

CODEC’s founding members

Barbara Predan, founding member

Assistant professor, theoretician, designer and author. Co-founder and leader of the department of design theory at the Pekinpah Association (pekinpah.com), and director of the Ljubljana Institute of Design, an academic research organisation. She has published several professional and scholarly articles and is the author or coauthor of four books. She has edited ten books and curated ten exhibitions. She regularly lectures at international academic and professional conferences, and, with Černe Oven, leads a number of workshops in the field of service and information design.

Kate Spacek, founding member

Kate has lived and worked in the Czech Republic since 2011, and has been part of CZECHDESIGN.CZ for almost as long. Her role as international projects coordinator covers working with multi-national teams on projects, grants and exhibitions. She studied BA Photography and MA Landscape Architecture in the UK, and she works a landscape designer and program manager for international student study trips, as well as a copy writer for Czech design firms.

Michala Lipková, founding member

Designer working along boundaries of UX, product and communication design, currently co-founding a hardware startup Benjamin Button. Michala leads commissioned research projects at the Institute of Design at the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava. Since 2013 she is a managing director of collaborative platform Flowers for Slovakia, focused on promotion of Slovak design abroad.

Henryk Stawicki, founding member

Henryk offers a unique perspective as both designer and strategist and is capable of designing measurable, unique scenarios for the future. Leading a strategic-creative agency, Change Pilots (changepilots.pl), he helps organisations build strategies for services, brands and products using design mindset and process. Henryk consults and runs trainings in the field of design strategies and management tailored both for entrepreneurs and designers. He teaches Design Management and Design Thinking at the School of Form in Poland. Member of the Advisory Board at Gdynia Design Days and co-founder of CODEC. Always working in transdisciplinary teams, he offers a multicultural perspective thanks to his years of practice in New York City, Poland and London, in organisations such as Parsons School of Form, Replay Creative and studio student work at IDEO.

6.4: About CODEC

CODEC, the Co-Design Collaborative is a design driven interdisciplinary network of highly skilled and experienced individuals, companies, associations and research institutes in Europe. We co-innovate with our users by combining rigorous research, vast practical experience and in-depth know-how. We are driven by a common social purpose: to not only do things right, but do the right things.

Published by: CODEC, http://codec.network

Author: Maxim Dedushkov

Edited by: Barbara Predan

Copyediting by: Kate Spacek

Design: Dániel Kozma

Funded by the Visegrad Fund

Bratislava, Budapest, Ljubljana, London, Prague, Warsaw 2017