What is Enlightenment?

Enlightenment is a funny word. It has deep spiritual context from Buddhism and eastern philosophy. It is heavily associated with the 18th century Enlightenment era, also known as the Age of Reason. It is in the title of Steven Pinker’s new bestselling book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. So, what is enlightenment?

Enlightenment is a state of freedom. Not freedom from the forces of the outside world, but freedom from the prison of our own minds. In this post, I will explain my theory of enlightenment and how it can be attained.

In a previous post, I discussed the benefit of psychedelic therapy for a variety of mental health issues. This benefit seems to be related to the experience of ego-death, or the dissolution of the Self, which can be elicited by psychedelics. The Self is the feeling of being an individual who is disconnected from the rest of the world. When the Self is dissolved, people feel a sense of unity with the world and with other people, and also a sense of freedom. How does this experience translate into a psychological benefit? And what does the dissolution of the Self have to do with Enlightenment?

In short, here is my answer to this question, and my definition of enlightenment:

The Self is the source of attachment to experiences. Attachment is the root of all suffering. Suffering is the cause of all negative, maladaptive, and irrational behavior. Suffering also causes one to maintain false assumptions that negatively influence behavior. By breaking down the concept of the Self, one can lessen attachment, and therefore lessen suffering. Without suffering, one can behave rationally. That state of non-attachment and rationality is enlightenment.

Allow me to elaborate:

The Nature of Suffering

“The Root of Suffering is Attachment” -Buddha

Buddhism teaches a path of non-attachment that leads to enlightenment and freedom from suffering. Suffering occurs when we are attached to an experience. If we want that experience to stay the same, we suffer if it changes. If we want that experience to change, we suffer if it stays the same.

Many pleasures in life are marred by our inability to accept that they will pass. We want permanence in a world of impermanence.

Many negative experiences are worsened by our constant desire for them to change. We want control in a world that is uncontrollable.

The key to avoiding suffering is acceptance and non-attachment. Seeing every experience as impermanent and embracing that fleeting nature. Experiencing life without trying to cling to it or change it. This concept seems simple, so why are we so bad at it?

What is the Self?

You are an area of consciousness, a locus of awareness. Your awareness cannot be separated from what it is aware of.

There is no Self that is observing and judging, separate from awareness. What we feel as the Self is actually just another product of the mind, a chain of thoughts with which we strongly identify. That string of thoughts, that feeling of selfhood, is no more “you” than the contents of your visual field, the feeling of your feet on the ground, or the song you are listening to.

This understanding of the phenomenology of being alive is referred to as non-duality. We almost always incorrectly think that there are two components to an experience, a duality: One is “You” and the second is the experience you are observing. In reality, there is just one component to consciousness: the experience. This can be directly observed with focus and concentration. Let us quickly try.

After you read this paragraph, close your eyes and examine what is actually in your experience at this moment. There is the inside of your eyelids. There is the feeling of sitting, the pressure in your legs and back. There are sounds appearing and disappearing in the room. Thoughts, words, and images go through your mind and disappear. Where do those thoughts come from? Did you decide to think them? Look for a Self. Look for a control box in your mind where an unchanging and stable Self is sitting and deciding what you will say, think, and do.

You cannot find that control box. In each moment, there is simply what you are experiencing. You are awareness, experiencing the contents of consciousness as they arise. If there is no Self, what separates you from your experiences? In reality, nothing. You are identical to your experiences. But there is one experience that separates you from the rest of your senses: The illusion of the Self. That ceaseless chatter in your brain with which you identify and call your Self. That inner monologue of thoughts and desires is no more “you” than the feeling of your feet touching the ground. You do not know where those thoughts and urges come from. You do not choose them. But we identify with that feeling of Self so strongly that we let it separate us from all other experiences.

The Self is an extremely useful adaptation that gives us a sense of continuity and agency. It allows us to make sense of our experiences by giving them a frame of reference, a center to attach to. This is what lets you know that you should eat when you experience hunger. You experience a sensation of hunger, think “I am hungry,” and go get food. With no Self, you would instead think, “there is hunger” and perhaps let that thought drift away while you starve.

While the Self is adapted for survival, it is maladapted for happiness. Instead of thinking “there is sadness,” we think “I am sad.” Instead of “there is anger,” we think “I am angry.” We attach to and claim ownership of these thoughts and emotions. We reinforce and legitimize them. As Yuval Noah Harari discusses in his book Sapiens, humans are narrative creatures. Stories are how we understand the world, and in no case is that more evident than in the ongoing story of our own lives.

Imagine someone cuts you off in traffic. You feel the emotion of anger and think, “I am angry.” You then let that emotion endure and control the rest of your day. You go to work and you are angry because there is the recurrent thought of “I am angry.” Maybe you are rude to a co-worker. Why? Because that thought of anger activates patterns of behavior that you associate with being angry. It gives you an excuse for those behaviors. It fits in with the story that your brain is constantly constructing to make sense of the world. The story of a bad day that is perpetuated by the narrative in your head.

Contrast that with the Selfless scenario. You are cut off in traffic and you feel the emotion of anger and you think, “there is anger.” That thought, and then the emotion, soon fade away. You go about your day normally. The story is free to unfold how it will, without the shouts of an angry director controlling how you will act.

That is the power of the Self.

The Self is the Root of Attachment, Attachment is the Root of Suffering

An excerpt from Finding Freedom, an earlier post from this blog:

“Imagine yourself floating in the ocean. When you are free — not attached to anything, not trying to stay the same in an ever-changing world — then you are able to rise up with the waves and come back down. You flow with the forces around you instead of being battered by them. In contrast, if you are anchored to one place, fixed and immovable, the waves will crash over you, overwhelming and terrifying.

The feeling of being anchored instead of flowing is the experience of feeling like a self.”

Attachment is the root of suffering across many different levels. When we become attached to another person, we give them the power to hurt us. If you love someone, you will hurt when they are hurt, if they leave you, or if they die. I happen to think that this high-level form of attachment — love — is worth the suffering it may bring. Attachment can be a good thing, so the question becomes what do you want to attach to, and how strongly?

You are eating a delicious ice cream cone. Your favorite flavor, two scoops. You can experience the delicious taste over and over again until it is gone, non-attached. Then you move on with your day. Or you can get attached. You have your first bite, and it is perfect. Your evolutionary adaptive Self decides that bite was good, so we better maintain it forever. That desire is in direct conflict with the reality that the ice cream will soon be gone. The conflict creates anxiety. Each moment is spent thinking about how the ice cream will soon be gone, or how you can get more once it is gone. The thoughts are so prevalent that you do not even appreciate or enjoy the ice cream while you are eating it.

Both these situations look exactly the same on the outside: you eat the ice cream until it is gone. In the non-attached version, you enjoy it blissfully. In the attached version, you barely even taste it while suffering instead.

Now let us go down to a more basic level of experience. The experience of sadness. You can think, “there is sadness,” experience the emotion, and then watch it eventually pass away. Or you can think, “I am sad. ” You can attach to it, causing it to control your narrative and color the rest of your daily experiences. You do not want to be sad, so you try to change your experience. You suffer because you want things to be different than they are. You fight a battle with yourself, trying to get rid of the emotion you are paradoxically clinging to. You suffer from clinging to it, and you suffer from trying to change it.

The Self is the source of all attachment because it is the reference point that makes it possible to attach at all. Without the Self, we are just bobbing along in the ocean, experiencing what comes by. We are identical to our experiences, good or bad.

With the Self, we attach to an experience and force it to persist. Yet the world is impermanent. The situation changes while we cling. We are holding on to a rock in a stormy sea, battered by the waves of change.

Without attaching, we do not suffer from bad experiences. In reality, there are neither bad nor good experiences: there are only experiences. Our narrative, the story in our heads, paints experiences as good or bad. We create our own reality. We create our own suffering.

Suffering comes from wanting things to be different than they are. From trying to change reality. Running out of ice cream does not have to be a bad experience. It can just be an experience. Being stuck at a stoplight is a normal, neutral experience. But if you are late for a meeting, and trying your best to will the light to turn green, you will suffer. This principle of attachment scales up to any level of negative experience. It is always possible to accept that “this is the way things are right now” without trying to change your experience. Bolstered by the knowledge that everything is impermanent and this too shall pass, suffering becomes avoidable.

Suffering Begets More Suffering

Through loosening the hold of the Self, we loosen attachment. By loosening attachment, we decrease suffering. This is important because suffering is the root of many of our worst behaviors.

We like to believe that our rational brain, our cortex, is in control of our behavior. The truth is, our cortex is often at the mercy of our limbic system, the emotional lizard-brain. What determines when emotion will win out over reason? Suffering.

When we suffer, we activate the limbic system. The limbic system then takes the reigns, doing whatever it can to alleviate the suffering. It takes control of the rational cortex and uses all of that incredible cognitive power to devise a plan to end the suffering. However, the limbic system is in a state of panic, so it goes down the easiest and quickest path. This path may be eating unhealthy food or using addictive drugs. It may, in fact, be any number of bad decisions — shirking an important responsibility, cheating on a spouse, shoplifting — whatever presents itself for a quick relief.

The cortex can also hide from suffering in more insidious ways. We sometimes suffer when other people suffer. Other people suffer often. When we suffer, the last thing we want is to be burdened with the suffering of others. Our brain can get around this by telling us stories: those people deserve to suffer. We spin a tale of justice that makes us think those people got what they deserved.

Our brain can also make us discount the suffering of others. We dehumanize them. We ignore them. We create a narrative for why their suffering does not matter.

Does anyone really deserve to suffer? Is the world really a better place when someone is in pain, regardless of what they have done previously? No, it is not, but the lizard brain will have our rational brain fool us into believing that it is. This is a cognitive defense mechanism, a quick escape from empathic suffering.

Our suffering isolates us from others. Our suffering keeps us from helping those who need it the most.

Suffering begets more suffering.

Attachment is the root problem, and detaching from that suffering is the answer. As discussed in my previous essay, psychedelics have been shown to quickly thrust someone into a selfless state. A common takeaway from such an experience is the realization that love and compassion for everyone is the rational way to view the world. This should not be written off as “Hippy idealism.” This insight is born from reason and a clear view of cause and effect. It comes from a more complicated lesson, one of determinism.

Why should anyone suffer? We have irrational constructs like fairness and justice that help us cope with our own suffering by making the suffering of others seem acceptable, or even necessary. Those constructs fall apart under careful scrutiny of the idea of free will.

The Illusion of Free Will

“Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills.” ― Arthur Schopenhauer

The concept of free will is entirely necessary for us to operate functionally in the world. It is useful, but it is not rational. We live in a determined universe, where every thought we have and action we take is decided by the thoughts and actions that came before it. We are a product of our genetics and our environment. Nature and nurture. Our genetics and environment were decided by the thoughts and actions of others who came before us. Those people were products of their genetics and environment. One can trace this chain of causality back to the origin of the universe. There is no room in this sequence of cause and effect for the concept of free will.

Take this quote from Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut as an example:

“I am a Tralfamadorian, seeing all time as you might see a stretch of the Rocky Mountains. All time is all time. It does not change. It does not lend itself to warnings or explanations. It simply is.”

This realization can be a destabilizing at first, but it does not have to be. While a deterministic view of reality is correct, it is practical to behave as if we have free will. We can never know what the next determined outcome will be. For all intents and purposes, we have free will. Free will is a pragmatic truth, a metaphorical truth. Our choices matter.

While some alien being that views reality from a different perspective may be able to see what events will come next, we are stuck in our forward-facing perspective from which we will likely never break free. We are staring ahead at the blank canvas of the future, and in every way that matters, in every experience of consciousness, our choices matter. Our free will is a truth. A conditional truth, a practical truth, but a truth nonetheless.

As mind-bending as it can be, switching between practical truths and factual truths can have great value. Determinism shatters any notion of justice or fairness. There are no bad people and no good people. There are just people acting in a way that has been determined by their genetics and environment.

The only rational conclusion one can reach after this realization is one of love and compassion. Why should anyone suffer? It does not make the world a better place. It does not fulfill some cosmic truth of justice. It is simply a regrettable fact of the human existence.

If you have the correct starting point, determinism, all suffering is unnecessary and no one deserves to suffer. This changes your actions. This eliminates the false concept of hatred that corrodes your mind and everything around you.

This level of insight is yet another benefit of selflessness. When you are without a Self, you are detached from suffering. Your intuitions are allowed to line up with reality because you are not mired in denial and falsehood as a way to mitigate your own suffering. Getting lifted up to a plane of clarity, even if for a mere moment, can have lasting impacts on the way you see the world.

Awe-inspiring moments, mystical experiences, deep moments of concentration, and psychedelic trips are some methods of accessing unfiltered reality rapidly. Daily mindfulness meditation is a way to perpetuate that state over time. A constant degrading of the self, a degrading of attachment. Rational thinking can rule when the limbic system is quieted.

Blinded by Suffering

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” -Mark Twain

When you identify with the inner monologue — the Self, that random train of thoughts that are floating through your brain all day — you are more likely to believe those thoughts are true. They are familiar because they come from within. They match your intuition, but that intuition may not match reality.

Why is rational behavior good behavior? It is not inherently. Rationality is limited by assumptions and prior knowledge. We can act rationally based on false assumptions, leading us to incorrect conclusions. Those false assumptions are often products of the mind working to avoid suffering. Other false assumptions are simply remnants of evolution, shortcuts and heuristics that helped us survive in the past but have outlived their usefulness and now propagate suffering and ignorance.

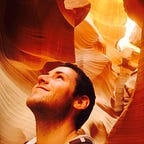

These false assumptions can be broken down through non-attachment. Non-attachment can be glimpsed from selfless experiences. These can include moments of awe, like watching a sunrise over the Grand Canyon. It can be seen through spiritual experiences: meditative, psychedelic, religious, or otherwise. And this selflessness/non-attachment can be stabilized through the practice of mindfulness and meditation. This is the path to Enlightenment.

The Freedom of Reality

Think of the composition of the word enlightenment. What comes to mind? Seeing the Light. Overcoming darkness. Severing attachments and weight to become Lighter: transcending evolutionary and physiological mechanisms that keep one tethered in place. Freedom.

The Enlightenment of the 18th century Age of Reason is of a piece with the concept of enlightenment in Buddhism. Both involve seeing the nature of reality clearly. 18th-century philosophers looked outward to divine the truth, utilizing the scientific method and reason while abandoning the dogma and ignorance of the past. The Buddhists looked inward to find reality, seeing that all the truths of existence can be observed with careful attention to the present moment.

Reality intertwines everything, and its fundamental truths can be evidenced across every discipline, manifesting in similar but unique ways. The Self can be degraded by looking at the vastness of the night sky, or the infinite expanses of the human mind.

A scientist can understand determinism through physics and reason in the same way that a meditator can gain the insight through a careful observation of the appearance of thoughts in the mind.

You can see the truth of impermanence in the death of all living things. Or in the second law of thermodynamics: entropy. Or even in the way every thought and emotion will inevitably disappear and be replaced in your own consciousness.

These truths free us from the bonds of our subjective reality. In our subjective reality — in our minds — we see a warped view of the world. We see a world of permanence, simplicity, good and evil, hatred… And we let that worldview determine our mood, our actions, and the course of our lives.

The Power of Detachment

“Attachment is the great fabricator of illusions; reality can be attained only by someone who is detached.” -Simone Well

Imagine your mind as a simple circuit, as seen below:

When the wires are connected to the battery, the lightbulb turns on. When disconnected, the lightbulb is off. Simplified, this is what our minds are like when we are not paying attention. When we see something scary, we react with fear. When we see something unfamiliar, we react with disgust and suspicion. When we crave sugar, we react by eating sweets. Stimuli → Perception → Response. Enlightenment is the power of detaching from that circuit. Understanding that you can light the bulb on your own terms. You can watch the wire connect to the battery, you can see the pathway fire, and choose how to respond instead of reacting. Detachment is Freedom.

Enlightenment is a journey. A journey of understanding, insight, and non-attachment. What is the destination?

Enlightenment Now

“The Path is the Goal” — Mahatma Gandhi

I am not “Enlightened.” I never will be. What would such a state be like?

Total non-attachment to all thoughts, emotions, and sensations. An entirely accurate view of reality, with no distortions or shortcuts of perception. An ability to see every stimulus enter awareness without the compulsion to react to it. Simple awareness of all the contents of the human mind. No suffering, no desires. Total awareness in perfect peace for the remainder of one’s time on Earth.

While this is an intellectually interesting mindstate to ponder, I believe that it is impossible to obtain with the limitations of the human brain and body. Even if this mindstate is obtainable, perhaps through decades of silent meditation in a cave, or with cybernetic enhancement, I am not convinced that reaching the pinnacle of enlightenment is a worthy endeavor.

Mindfulness, enlightenment, selflessness, detachment… these are journeys without destinations. I do not meditate to become a better meditator. I meditate to become a better human. To interact more skillfully with the world and other conscious beings.

I do not attempt to make myself more rational so I can become a computer. I do it so I can see the world more clearly. So I can reduce suffering in myself and others.

The path is the goal.

Enlightenment is the state of freedom that comes from selflessness, from detachment, from mindfulness. Whether that state lasts for one second or for one day, it is valuable.

I do not need to spend eternity in that state of enlightenment. However, I know that by spending some time there, I can improve my relationship with myself and with others. With the right balance, I can become a more rational and compassionate being.

With these methods, I can avoid the traps of letting suffering cloud my vision. I can internalize truths like determinism and impermanence, and reap the benefits they bestow. I gain the freedom to respond instead of react. I gain the freedom to choose.

My purpose is to decrease the suffering of conscious creatures. That is what is meaningful to me at this point in my life, and it manifests itself in many different ways. Whatever your purpose is, freedom from the chains of your physiology will help you fulfill it.

Enlightenment is not a mystical concept from Eastern Philosophy.

Enlightenment is not a period of history that we have left behind.

Enlightenment is freedom, and it is accessible at any moment. All you have to do is look. Value reason, truth, and reality. Carefully observe what is happening in the world and in your mind. With focus and practice, you can find Enlightenment, now.

If you liked this article, here are some related posts you might enjoy:

What is a Drug? — The Problem with Oversimplification, Stigma, and the Current View of Mental Health

Finding Freedom: An Exploration of Growth, Meaning, and the Mind